Director Nancy Biurski and company didn’t opt for Directed by Sidney Lumet; simply By Sidney Lumet. It’s the kind of possessory credit that would have been bellowed out at the director’s Mecca that is Cannes, where Lumet’s sixth feature film was presented in 1962: Long Day’s Journey into Night, de Sidney Lumet!1 The highlighting of this particular detail may appear to suggest that Lumet was not a filmmaker of singular vision and influence, one who utterly suffused collaborative undertakings with his own neuroses/fixations and branded them with a personal stamp, formal or otherwise; basically, that the term ‘auteur’ does not become him. Well, if – in cinema’s grapevine – there are indeed murmurs that Sidney Lumet was a mere Hollywood journeyman, churning out 44 garbage-to-great features in a 50 year career without any discernible artistic through line, Buirski’s By Sidney Lumet quietly objects, beginning with its title.

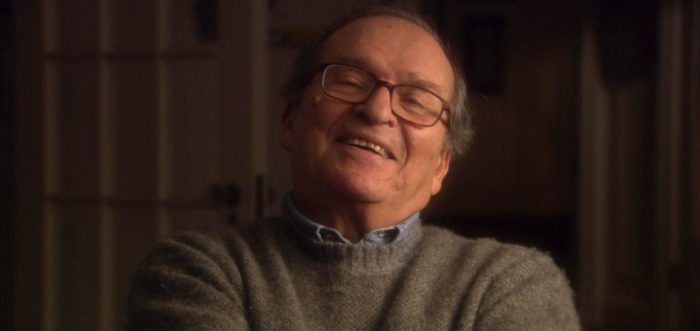

Assembled around an interview conducted one year after the release of Lumet’s swansong feature Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) and three years before his passing at 86, Buirski’s gently reverent portrait is fuelled primarily by the eloquence and unshowy intelligence of its subject, the man behind the original 12 Angry Men (1957), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), Aaron Sorkin’s beloved Network (1976), and a very fine dirty cop picture deemed ‘remarkable’ by Martin Scorsese, the lesser known Prince of the City (1981).2 Having stated that he is “not comfortable anyplace but New York” and that he “wouldn’t know what to do with a western,” Sidney Lumet’s status as a quintessentially ‘New York’ filmmaker is superseded only by his commitment to civic-mindedness and an attraction to underdogs and radical who, in Lumet’s opinion, “always have something to offer.” For his headlong tackling of everything from police corruption to the politics of sexuality, Ebert would label him a ‘humanitarian’ among directors.

A series of moodily lit close-up shots punctuated by clips sourced from Lumet’s vast filmography, By Sidney Lumet is essentially a two-hour monologue which would quite frankly have run aground were Lumet not so focused and commanding a talking head. Largely free of those meandering showbiz anecdotes, the relative sense of focus is to the credit of Buirski and her editor Anthony Ripoli, who choose to bookmark the film with Lumet coming to terms with a sickening act he witnessed while stationed in India as a radar repairman during World War II. Lumet’s regrettable impotence in the face of such barbarism is positioned as a moral turning point for the future artist, and a continuous source of productive guilt. It thus makes sense that, in characterising his work, Lumet states that “there is always a bedrock concerns of ‘is it fair’?” And while it is admittedly a tad convenient to attribute an entire life’s work to one moment (however pivotal), Buirski’s decision to explore Lumet as an ‘artist of conscience’ is far more admirable than a plain old cradle-to-grave biographical approach.

It must be said, though, that there is something regrettably staid about Buirski’s approach to the archival footage. While no one expects Thom Anderson-level metatextuality, the semi-chronological rollout of samples from Lumet’s directorial work rarely acts as an interrogation/investigation of his particular brand of cinema; its evolution over the decades. The clips generally serve as supportive material and are rarely commented on by Lumet, further reinforcing the idea that Lumet was a man of the message more than he was a man of the medium. Of course, anyone acquainted with Lumet’s pseudo-memoir Making Movies will attest to his pragmatic craftsmanship and his on-set smarts. Which raises the question with which Buirski’s film must contend: what insight can be gained by viewing this picture which cannot be gleaned from Lumet’s book, or which cannot be tapped into by listening to his many gracefully candid commentary tracks? The answer is: probably not much in the way of biographical details or glimpses into his artistic process. This documentary is, in a way, a call to reappraise Sidney Lumet’s artistic purpose and his claim to authorship, but on the basis of his ideologies as opposed to his craft.

It’s interesting to note that By Sidney Lumet premiered at Cannes 2015, alongside Kent Jones’ Hitchcock/Truffaut, another director-centric documentary founded upon an admittedly far more famous interview in which Francois Truffaut exhaustively explored the workings of Alfred Hitchcock and spotlighted his genius. For three decades Lumet and Hitchcock were contemporaries. One (Hitchcock) has been widely misquoted as having called actors cattle when he simply posited that actors be treated like cattle – big difference; the other has been hailed as an actors’ director, one of his former cast members going so far as to call him “every actor’s dream.” That being said, both directors succeeded in summoning great performances from great performers. Each man can boast at least four films in the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry (five for Hitch), thanks in part to their being relatively prolific. Yet, Hitchcock’s status as a cinematic deity and a maker of personal art is now fairly undisputed while Lumet seems to occupy some space between ‘reliable’ and ‘respected,’ though a betting man may take a safe punt on the former.

Aside from his indisputable formal innovation (equalled by precious few, Lumet included), could it be that Hitch’s relative amorality and streak of perversity act as some kind of preservative, maintaining a degree of cultural relevance while Lumet’s socially conscious bent has a tendency to go out of fashion, however admirable? One would hope that cynicism is not so prevalent as to render Lumet’s earnestness outdated, but perhaps Buirski’s championing of Lumet would have benefited from a focus on the influence of – say – his muscular yet classical, performance-driven brand of storytelling. Lumet clearly has no designs on a personal moralist vision, certainly not when he says, “I’m not directing the moral message. I’m directing that piece and those people, and if I do it well, the message will come through.” So, at the end of it all, it may be that the ‘by’ in By Sidney Lumet is largely silent though present, very much in keeping with the man’s legacy.