Let’s talk about Tim Blake Nelson. Anyone who recognises him is probably thinking either of his performance as one of the three chain-gangers in O Brother, Where Art Thou? or his more recent one as the gormless father of The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidton Netflix. How many of you knew that he directed O, the contemporary version of Othello that you surely watched in high school? How many of you also knew that he’s directed six other features? He’s a Juilliard graduate who regularly appears in both dramas and comedies, showing both the idiosyncratic stylings of both a seasoned character actor and a dramatic artist. He’s also, oddly, no stranger to aborted attempts at Marvel Comics film adaptations. He appeared as a manic secondary villain in 2008’s The Incredible Hulk, more known for wall-to-wall CG slug-fests and Edward Norton than anything in the same league as the first Iron Man movie put out that year. His last shot saw him grin at the camera as radiation leaked into his brain, and so his destiny, thousands of fans immediately staked, was to be supervillain The Master in the inevitable sequel. Weak ticket sales made that evitable, Norton the Smasher was benched for Ruffalo the Avenger, and Nelson went quietly away to work for better directors than the likes of Louis Leterrier (freaking Spielberg, for instance).

Now history repeats itself and he emerges from the crumpled franchise dreams of Josh Trank’s notoriously botched Fantastic Four reboot as an unlikely star, whisking entire scenes away from Miles Teller1 and delivering expositional putty in a nonetheless fatal retooling mandated by the studio. No-one expected him to be such a focus, least of all that of a Hollywood corporation chasing a trademark renewal, but in this failed attempt to broach the hard-bitten world of cinematic universes and one-a-decade reboots, he is the morsel of integrity we have to subsist on. He shoulders a movie professing to tell a story on the sanctity and sin of scientific enterprise, but the few brushes it has with genuine glee and gravitas are swiftly neutered by a script (officially credited to Trank, Jeremy Slater and Simon Kinberg) that, like the image of its rubbery protagonist Reed Richards (Teller) splayed and traumatised on an operating table, strains tone and characterisation into incoherence.

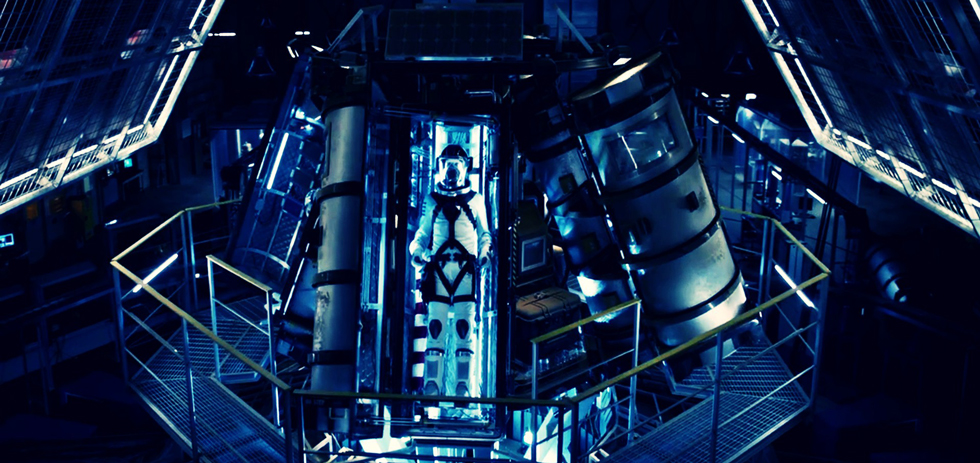

Our entry-way to this cosmic snafu is Reed and Ben Grimm (Jamie Bell), who bond as boys through a home-made teleporter, and their unity is stronger than anything Reg E. Cathey croakily instructs them on later as his elder scientist teams them with his aloof stepdaughter Sue (Kate Mara), her rebellious brother Johnny (Michael B. Jordan) and a reclusive, arrogant computer hacker, Victor (Tony Kebbell), at a scientific institute. There’s an Amblin tone to Reed and Ben’s early years, and the motley crew they form later feels like an enjoyable follow-through of that, to the point where the few creative embers trod underfoot by the stampeding critical schadenfreude can be found in the early scenes of their project assembly, with their successes and squabbles playing out amid Large Hadron Collider surrounds (Molly Hughes and Chris Seagers on production design). There are hints of the misfit bonding and mischief that fuelled the early portion of Trank’s feature debut, Chronicle, though transmuted into a more inspiring, doggedly determined take that would have done right by Marvel-loving youths more accustomed to “science” as a plot patcher than an aspiration if it had only been, well, done right. Such hints are fleeting, naturally, and once an impulsive teleportation to the vaguely defined Planet Zero goes awry and gives them superpowers, things head very badly south for them and the movie.

It’s after a baffling one-year time jump from this moment that Nelson rears his head at a board meeting to get shadowy government figures—and us, an audience similarly kept at a cold remove—up to speed on the team’s whereabouts. This part, where we’re told about Reed’s fugitive status and his co-workers’ new-leaf transition into government mercenary work, leads us so forcefully through the malaise of origin material as to make even the ski-resort tomfoolery of Tim Story’s 2005 origin story feel lively. The fact that neither go-around has even topped the Roger Corman version for its goofy simplicity is baffling, and among the cutaways to the distressed young scientists, Nelson grandstands like a boisterous substitute teacher, cleaning up the confusion as efficiently as possible. The other buoy in the sea of confusion is Cathey, who is strongly stoic even as his bold-faced insistence for them to trade their labcoats in for battle armour against a crazed, megalomaniacal Victor winds up as the telltale sign of how grafted-on the “fantastic” feels in Trank’s grim new take. Doom runs rampant with brain-squishing mind powers but then dons his iconic arch-villain cloak, Thing gets moody tête-à-têtes with his absconding friend Reed only to make a certain, familiar declaration about an instance of drubbing, and the enthusiasm tapers off to the level of a B-movie, with the characters bouncing around clumps of literally earth-shattering CG effects. The slightly charming film where child prodigies eat late-night dinners out of oyster pails becomes a dour one where they save the world with well-timed walloping. It’s like Big Hero 6 dipped in Prometheus sludge.

For all this, putting Fantastic Four‘s box office and production woes aside leaves nothing more than a malformed curio. The strong sense isn’t that Trank made a bad movie, but that his crew made a hash of what we know from the dated sequel was a long-run business plan. We’re as much to blame for this perception as the studio, though. We cry for originality one moment and then in the next kick a guy for failing to inhibit it properly, clapping at even the thinnest rumours that Kevin Feige may come and rub this unsightly blemish away with another reboot. Some then assert that this mess is exclusively a result of his shared-universe monstrosity, but whether it’s heroes, spies, star warriors or prickish dinosaur wranglers, it remains that we the audience crowd screens to see even a taste of what’s to come next for them, and then film ourselves watching what we see.2 The word “franchise”, once the domain of money handlers, might be something we drop in ordinary movie talk, but when multi-film contracts and crossover potential falls over, it’s properly independent, work-a-day titans like Nelson that we have left to admire. For at least a moment, let’s talk about them.