Based out of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Video Data Bank is a mostly academic repository of film and video art, housing a veritable treasure trove of cinematic content. Whilst its library is vast, access to films within it is nigh on impossible unless you happen to be large educational institution or screening space. This speaks a lot to the relative exclusivity of video art consumption, something particularly pronounced if you’re not based in America (like us).

Thankfully, the VDB do stream a select group of films for free online as part of a curated program, VDB TV. The latest program, curated by Nelson Hendricks, runs under the name American Psycho(drama): Sigmund Freud vs. Henry Ford and is an eclectic group of late 1990s video art looking at the interactions between people and popular culture.

To highlight this collection and the rare window into the VDB collection that it provides, a group of contributors here at 4:3 have conducted a roundtable discussion about the films curated.

You can watch all of the selected shorts for free here until mid-May.

Ivan Čerečina: Animal Charm work with a relative economy of means in their found footage work, Stuffing, which opens the program. At a guess, the constituent elements of the video are: a nature documentary on lemurs, an old television cartoon (Hanna-Barbera-era?), and what looks like a motor vehicle safety video. The pair keep their manipulations of these found sources fairly simple, experimenting with duration in cutting between shots/sources, looping shots and animated sequences, and the occasional use of slow motion. Interestingly, the piece seems to be edited according to the logic of snippets of sound that are peppered throughout, whether it be ambient nature sounds looped to create an odd rhythm of pops and bird calls, or the offbeat inserts of muzak that accompany the footage of a lemur dancing. There’s a quite deliberate sense of dislocation that these manipulations create, stripping each segment of its internal bearings and re-routing them into a kind of soothing soup of now-interwoven details. Something like hearing a word too often and forgetting what it means.

Conor Bateman: I’m somewhat familiar with the work of Rich Bott and Jim Fetterly, aka Animal Charm, because I’ve seen their shorts collection Golden Digest (which is still streaming on Fandor for those interested) so the set of shorts featured in this VDB series from them are all repeat watches for me (so I’m very keen to hear what you thought of Ashley later on in this discussion). This time around on Stuffing I was a lot more aware of the soothing muzak that loops after the first few jumps of the monkey/lemur; the re-purposing of corporate sound is almost proto-vaporwave in their work and taps into this pretty hilarious idea of life as recursive system.

Ali Schnabel: Proto-vaporwave, yes! Stuffing almost feels like a meme in its end stages: completely nonsensical and repetitive. I like the juxtaposition between the snippets of nature documentary and over-editing in this: the idea of refitting nature with a human paradigm and fabricating emotion/interactions between animals. Like when your dog puts his head on your lap and you think it’s because it loves you but it’s actually that it just wants your food; the preposterousness of ascribing human emotion into places where it doesn’t fit.

Luke Goodsell: This is a beautiful example of pre-digital editing; the natural, manic extension of every VHS kid’s obsession with pausing and repausing tapes to obsess over amusing moments. What’s impressive is the amount of work that’s gone into creating the rhythm of the piece, as I’m assuming this was all done in an offline edit, and the hours it must have required to fine tune this footage gives it a kind of patience in building tension and humour that would be too easy to achieve now—and probably not done as well as a result. I loved the way this digs into the very simple cell animation of those ‘80s action cartoons and interrogates the sequence until it becomes a mantra of lunacy; the lemur’s response to this looping human error says it all.

Ivan: Two grown men sitting at a table try to save themselves from the perilous sci-fi scenarios that they keep imagining and acting out with everyday household items. It’s a great set-up for a comedic sketch that, like Stuffing before it in the program, goes for repetition and displacement as the source of its key intellectual provocations. HalfLifers’ Control Corridor opens with a (probably improvised) dialogue exchange between the two actors — both dressed in their best makeshift futurist costumes — about “doing the tractor sequence”, which acts as a prompt for a series of botched and increasingly overwrought attempts to animate a toy tractor and make it seem like a spaceship of sorts. The sequence breaks down as the two men start discussing instead whether their characters need to change names to “activate their purpose.” This inane back and forth, accentuated by the two camera set-up that carefully keeps each character in separate shots, becomes the grist of the rest of the work. Frantic attempts at communicating across the table/the cut take over the two characters as the household objects that act as stopgap sci-fi prompts (a rotary dial phone, a motorcycle helmet, candle) prove increasingly hard to contain in their on-the-fly fantasy scenario.

Luke: One of the overall impressions I get from this collection is that of Gen Xers wrestling with the inherited cultural detritus of post-War America—the “kind of panic” induced by mass-produced objects, as Henricks puts it. This was a generation raised on television, much of it terrible, but rather than taking form in the dreaded irony and quotation of the period, this series addresses that phenomena by rendering it through dislocation and madness. HalfLifers’ work here seems especially emblematic of that, in that they’re literally surrounded by consumer junk through which they perform. For some reason I assumed the two guys here were either recording dialogue for a film or acting out a screenplay they were writing, with the relative earnestness of their dialogue being undermined by the absurdity of the objects they were using to communicate it. I know that’s off-base, but whatever they’re trying to communicate there’s a sense of behavioural retardation in the way their performances resemble those of children—as though their primary developmental role models were the kids who acted out action toy scenarios in TV commercials.

Conor: I also thought in some respects it was dialogue based moreso than visual. For a section I just closed my eyes and pretended it was an absurdist podcast, a less on-the-money episode of Comedy Bang Bang, perhaps. The two HalfLifers shorts in this series actually didn’t do too much for me in terms of provoking thought or engaging me, though I think Control Corridor is the weaker of the two. There are some interesting ideas in its internal structure and the looping of an ‘emergency’ narrative, though.

Ali: I agree with Conor here – the HalfLifers shorts didn’t really take me anywhere beyond “this is like kids playing adults”. Not that they weren’t enjoyable to watch –they were quite funny– but I did struggle to a bit with the narratives. Maybe it was the length? They just felt a bit one-trick-pony-ish.

Ivan: There is some fantastic animation work by Emily Breer here that half illustrate and half hi-jack Joe Gibbons’ three tall tales that comprise The Phony Trilogy. Gibbons vividly recounts his outlandish encounters with celebrities in the past directly to the camera, waxing lyrical about his having inspired Brian Wilson to write the Beach Boys’ summer-themed hits or how he almost replaced Iggy Pop on tour after they played a game of golf together. Breer bleeds Gibbons’ fantasies into the images, transforming the mundane objects that are his props into material for his aspirational stories: a diving board becomes a surfboard on the beach in 1963, a putter a guitar that Gibbons is soloing on at a rock concert. I’m not sure Breer and Gibbons really draw much pathos out of this somewhat pitiful character but perhaps that’s not really what they’re going for here?

Ali: I like your point about Breer’s animations transforming Gibbons’ props into his aspirational stories: it’s kind of like an elucidation of his delusions, an operationalisation of his fantastical tall-tales. I think Gibbons takes it a step beyond pitiful here: he is spilling over into legitimate, clinically diagnosable delusion here. They’re all tinged with a theme of grandiosity, of the self-aggrandising. I find the demarcation of Gibbons’ roles in these fantasies interesting: he is the Pool Boy, the Caddy, the Vietnam Vet. These are all intrinsically servile roles where the nameless individual does the bidding of the master – not coincidentally, Gibbons fixates on pop culture icons (Brian Wilson, Iggy Pop, Francis Ford Coppola) as his ‘masters’, but he attempts to regain agency by pledging his own influence. It’s uncomfortably, pathologically pitiful.

Luke: This was almost like Snapchat for aspirational psychotics, which is obviously an idiotic way of putting it but I loved the way the animation both supplemented and mocked Gibbons’ characters and their fanciful stories. Although this is performed by an actor, it feels of a piece with the tradition of delusional storytellers whose experiences have become inseparable from the pop culture that envelops them. I feel it’s probably too staged and comedic to have the pathos of, say, Trent Harris’ The Beaver Trilogy, but it shares the same sort of awkward, deluded confessional.

Conor: Outside of the pretty entertaining and impressive animation, The Phony Trilogy just kept confirming in my mind the sense that a fair amount of character-based video art are just mostly unsuccessful pieces of sketch comedy presented in a manner that makes them easily amenable to academic analysis or critical discussion. Gibbon’s recurring phony character felt like a skit from The State, sans the wit. The pathological element that you raise, Ali, does make sense of the need for animation and alteration of the narrative frame, but as it stands outside of a window into late ‘90s animation-over-film techniques, these left me pretty cold.

Ali: I’m not sure The Phony Trilogy ever intended to channel humour, though. To me, it felt like it was using ‘humour’ (admittedly, a lazy attempt at it) as a means of forcing the character to engage with the protagonist: we are kind of forced to laugh because, if we engage with the delusions on face value, it means that we are looking at something very ‘crazy’ and that is quite uncomfortable. I think a lot of Gibbons’ work channels this sense of blurring the lines between the performative and the actual, by blending his own neuroses into his work.

There’s a quote on The Phony Trilogy from Hendricks’ essay that I feel nails the ethos of the three pieces better than I ever could:

“Gibbons is not just working class, but serving class. Illusions of class mobility are propagated through tantalizing visions of fame, yet in reality, they remain nothing more than this.”

To me, the poorly formulated, phony character is a vehicle for audience discomfort, as an injection of Gibbons’ personal (mental health, dispossession, etc) into his art. But, I feel you when you make the point about it being easily amenable to critical discussion: I am definitely drawing a lot out of this that perhaps, is grasping at neurotic straws.

Conor: I wouldn’t go so far as to say you’re grasping at straws but I think where we differ is on this idea of intentionality. Using humour and our engagement with that to prompt further reflection fails somewhat when the intended humour doesn’t engage us. Part of that, for me, is definitely retrospectivism. Looking at these shorts now, perhaps the approach to shortform comedy taken in these shorts hasn’t aged well but was contextually relevant or in keeping with popular culture of the time. I also think that the title itself, with “phony” in it, suggests a mocking of the characters’ delusions and the perceived universal desire for fame inherent in these monologues moreso than some empathetic channeling.

Ali: Set to the tune of discombobulating, down-tempo Country music, Anne McGuire’s I Am Crazy and You’re Not Wrong sees her play a Kennedy-era singer who performs a variety of pathetic and poignant songs for a detached audience of questionable reality. McGuire weaves the trope of the unstable or bizarre female performer (e.g. Amy Winehouse, Bjork) with an unsettling sense of discomfort. No longer able to remove themselves from the performer’s troubles, the audience is forced to introspect and reflect on their judgements of the female performer. As things unravel in I Am Crazy and You’re Not Wrong, McGuire provides a critique on the consumer-driven performative arts that often fail women spectacularly.

Luke: It’s interesting you bring up the notion of the “unstable female performer”, because I think McGuire is exploring an era where pop singers were presented as extremely stable—which was frequently at odds with both their personal lives and the often dark undertow of the lyrics to their songs. I’m thinking specifically of people like Lesley Gore, whose TV appearances this echoes to an extent, but also of the many lyrics in which female singers would express their devotion to their men despite being obviously abused (“he hit me and it felt like a kiss” etc). McGuire gets this perfectly in the “I’m crazy, you’re right” vibe here. What’s most wonderful about this work is how it explores all those weird spaces inherent in the lip-synched performances of the era: the forced smiles and cheerful outfits that belie the doomy scenarios. There’s also a nice touch of Andy Kaufman to the off-kilter backing track and out-of-sync vocals.

Conor: Kaufman, yes! I think McGuire, in both this short and The Telling, has such a fascinating grasp on character and character types. Here it’s a ‘60s era popular singer (I think? I’d have to side with Luke on this one) and the short plays as excerpts from a TV airing of her special, though the camera angles slowly move away from this conception, as does the jarring out of tune and out of sync vocals. The way McGuire whispers at the end of each track is so funny to me, as if her inability to wink to the audience. She’s mocking as much as she is writing a love letter to the era of singers, using the genericity of “I wrote this song when I was unhappy” as a lead-in to a song that has vocal delivery that lands halfway between Broadway standards and a US Girls track. The sense of delusion and internalised expression that The Phony Trilogy might have been getting at is so much more efficiently despatched in one cut in I Am Crazy – at the 7:50 mark where there’s a sudden costume change yet no break whatsover in the song, the change achieved through a cut rather than any physical gestures.

Ivan: There’s something quite hypnotising about McGuire’s film because it really calls into question a lot of issues to do with performance, particularly being in control of your image as a performer. At first, I cringed at the idea of this just being a parody of old-timey pop stars, but as the work goes on, it develops into a slightly more complex consideration of what it’s like to get up in front of other people and embody an artistic persona. I think Luke is right in pointing out that it’s the “instability” of her performance and how an audience might perceive that — both evoked in the title — that make this an interesting piece. We think at first “oh, she’s delusional, she thinks she’s Peggy Lee” but for me that was quickly supplanted by a reflection on how all of these televised performances involve some kind of delusion on the part of the performer about reaching out and embracing their audience. McGuire’s seamless adoption of the codes of televised music performance and the ambiguity created by the ghostly audience noises that we hear briefly really feed into this — who is she performing for here, anyway?

Luke: My favourite piece in the series, and something of a masterpiece from Animal Charm is Ashley, which charts the voyage of an ordinary housewife—via sitcoms, infomercials and Videodrome—as she enters, or bears witness to, some sort of parallel-dimension cult in which power-suited ladies worship/draw energy from a giant cube. At least that’s what I think was happening. Whatever it is, the psychic transaction is compelling and hilarious and somehow affecting, skillfully mixing the cheese and banality of its found footage with a thesis on (I think) soul transference through which Ashley is transformed into her cosmic, pixellated ideal. Animal Charm resist mocking or parody and take the more rewarding path of finding the sublime in the source material, where actors-playing-housewives pretending to be mesmerised by life-changing consumer items becomes a real, transcendent phenomena.

Conor: I’m so glad you loved this one, Luke. I think Ashley is one of Animal Charm’s best shorts, not only acting as a montage of pre-existing material but creating this almost tangible space – Luke, you put it as a parallel dimension cult but I think it’s got more in common with the crisis of self that comes with excessive consumption of television. The opening montage, with fart noises and a shot of a toddler in a car seat, instantly called to mind the harrowing Adult Swim short Unedited Footage of a Bear, but Animal Charm achieve similar effects with only found footage.The floating personality cube, which in its original incarnation is meant to reflect the worldview of different types of women who can be advertised to by cosmetic and fashion labels, suddenly gets hijacked by a food commercial and a cowboy driving a truck whilst sipping coffee. This scrambling of the source signal suggests an initial incoherence in identification with abstract images but its sense of timing and wilful embrace of the absurd turn it into a pretty hilarious piece of video art.

Ali: I really, really dug Ashley – I feel like it really nailed the absurdity of its source material (as a busy modern woman, I know I love to draw all of my cosmic energy from a giant cube) without being snarky (as would be easy, and tempting). It digested the absurdity of the whole ‘feminine transcendence’ that you so eloquently noted, Luke, and took it quite literally. In turn, Ashley felt kinda like a Brand Power commercial for cosmic nirvana.

Ivan: Technique-wise, there are definitely a lot of parallels between this and Animal Charm’s other short in this series, Stuffing — especially in the first couple of minutes, the pair create rhythmic structures out of the source material via loops and overdubs “forcing,” in Hendricks’ words, “the television to babble like raving lunatic.” Once again working with the detritus of mind numbing daytime TV, the directors extract and hone in on the moments that hint at a world outside of the facile self-help narratives these television productions are charged with creating. Reading back on Luke’s comments, I can now see the voyage of Ashley in the film but to me the structuring principle was more thematic than narrative. For me, it’s about the kind of “cosmic nirvana” (as Ali put it) offered by the confluence of mass-production and technology, embodied in the shoddy daytime television that is the source material here. The sequences focus in on characters being offered ideal solutions and their reactions to it, exemplified by the short/reverse of the couple watching television themselves on the couch.

Conor: Actions in Action is the slightly more accomplished of the two HalfLifers shorts, wherein the two men, donning makeshift superhero costumes (made from construction gear, welding goggles, a martial arts vest and more) frantically pace around a kitchen trying to mix ingredients to find an antidote to a mysterious illness. They smash through yogurt cups, Gatorade (after pouring it on himself, one of them says “I can totally tell where I’m supposed to be now”) and a strange red liquid, finding a solution in a can of pineapples. Their voices are pitched up as well, almost to Alvin and the Chipmunks heights, and the whole thing gains a disturbing air as a result of its relation to childlike play. It’s similar to Control Corridor but I feel this short better used its runtime, or relatively justified its length.

Ivan: I’ve got to disagree with Conor, I thought this was the weaker of the two HalfLifers shorts, though maybe that was just because it’s so similar to Control Corridor, which I saw first. The set-up is almost identical in Actions in Action: another futuristic fantasy is dreamt up by our two male protagonists with the help of household (and particularly kitchen) goods. Once again, it’s a heavily improvised piece, with the two actors literally emptying out their fridge as they reach for something to sustain their frantic, high stakes interactions. While I didn’t actively dislike this, it just got the point that I’d seen enough meat products as consciousness-enhancers or energy drinks as memory-aids that it did get a little tiresome by the end. Yes, you are re-purposing another mass-produced consumer commodity for child’s play, once again…

Ali: I very much agree with Ivan here – what started off as comical and perhaps interesting just became so bloody tiresome. Maybe the whole criticism of mass-produced consumerism would have hit harder back when Control Corridor came out, but that stuff just doesn’t strike a chord with me anymore – I’ve just been overwhelmed with it. I just want to eat shitty supermarket ham, okay?

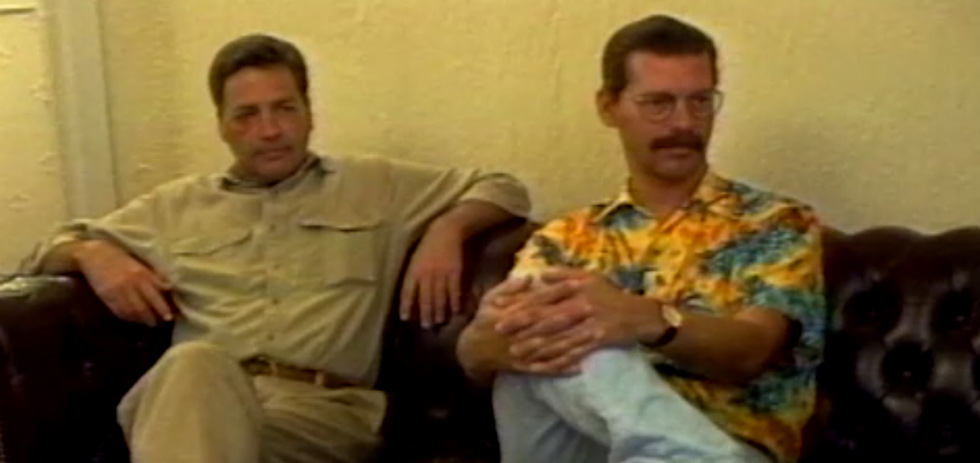

The Telling is probably the most ambiguous of McGuire’s pieces in the collection, and it seems purposeful. The setting appears to be three friends talking, but meaningful pieces of dialogue are removed until the end. The couch the two men sit on made me think immediately of a therapists couch, so I took McGuire to be therapist to the two men (perhaps couples counselling?)

Something I’ve been thinking about a bit in the course of my day job (clinical psychology postgrad student) is about the distinction between therapist and client in the context of mental health concerns: the therapist assumes a role of a healthy individual who seems so devoid of mental illness that they’ve risen above the phenomenon to dissect and treat it. Obviously, that’s not the reality, but in more didactic interventions like CBT, the therapist assumes a teacher role and not the role of a ‘fellow traveller’. Personal disclosures are frowned upon. To me, The Telling seemed to portray the elements of a therapeutic personal disclosure that made her clients uncomfortable; their walking out seemed to indicate a dissatisfaction with the service. The piece as a whole seems to reflect on the madness of the therapist and its lack of a home. I certainly think this is born out of my own experiences (especially so since the piece is so ambiguous), but I’d love to know what the rest of you thought of The Telling. It’s certainly an enigmatic one.

Conor: I really liked The Telling and not at all for the psychological reasons you’re able to draw from experience, Ali. I think it’s such an amusing short about the flow of conversation and the notion of real-life and real-time editing. The Telling opens on prolonged awkward silence, then onto her asking with a sense of familiarity and self-deprecation whether the two men in the room with her remember when she moved into her apartment. Their blunt, fairly cold answers cause this rift in the realism of the piece, paradoxically; the temporal nature and tone is steeped in realism but there’s this spearing of the familial warmth McGuire initially seems to have been setting the scene up with. When she finally, clumsily, reveals the secret the title refers to, the two men don’t seem too concerned or shocked. Instead they just sit in silence, stand, and leave the room, acting out the physical response to being duped without any tell as to the emotional impact of the process on them. Outside of all of these implications I also think it’s just such a funny three-minute watch.

Ali: I really like that interpretation, Conor. I really need to watch more movies and read less textbooks.

Ivan: Yeah I think I engaged with this work on roughly the same level that Conor did, which was as a kind exercise in disjunction within a fairly strict set of formal guidelines. What’s interesting about the piece is that it focuses on the telling of a story while dismantling the codes that allow for “successful” transmission of narrative information. Chronology is thrown out the window; cuts that appear to come from different takes or earlier moments of the sequence rub up abruptly against one another, with the effect being that not only is the story that McGuire tells out of order, but her telling itself is as well. In doing so, the suturing of space and time that is the grist of three-camera television shooting falls apart.

Ali: I find Gibbons’ work quite interesting, and I think Multiple Barbie was my favourite in this collection. In it, Gibbons plays a charismatic psychoanalyst who is attempting to draw out and reintegrate the multiple personalities of the mute Barbie doll. The audience can deduce two possibilities: one, that the doll is the intended recipient of the therapy, and that Gibbons is participating in a droll caricature of psychoanalysis. The second possibility is that Gibbons himself is acting out his own anxieties on the doll, interpreting them within a ‘multiples’ framework and personifying his neuroses. Gibbons’ genuine commitment to the performative makes it hard to discern which one, and therefore the audience is forced to oscillate between the two possibilities throughout.

It’s an interesting position of discomfort to be in: it harkens to the rest of Gibbons’ fascinating work in performance art quite well. We love to watch ‘crazy’ unfold, but preferably when it’s in a detached way: when the story is sanitised and brought under an appropriate growth/tragedy driven framework. What happens to the audience when the madman has the camera?

Luke: Ah Pixelvision, why did it never catch on? At least in more feature films, anyway—the only one I can think of is Michael Almereyda’s Nadja, which used the boxy frame and grainy black and white to useful vampire-perspective effect. It’s fitting here that Gibbons uses a Fisher-Price camera originally designed for children to psychoanalyse a Barbie doll; another refraction, obviously, of childhood clutter in these artists’ collected work. I can’t think of anything more ‘90s than a video involving a troubled plastic beauty princess, and this is a perfect complement to that whole kindercore aesthetic. (Ali said it all with the requisite eloquence.)

Conor: I too lament the non-starter that was Pixelvision. It reminded me too of a Michael Almereyda film, At Sundance, his documentary featuring interviews on the state of cinema which seems almost undermined by the PixelVision form. The adultification of taking a children’s toy and using it for an absurd session of psychoanalysis is interesting, though I’m concerned to some extent it’s mocking that profession implicitly. What do you think about that aspect, Ali? Obviously there’s a shift away from that in the film’s end, as it becomes an odd horror film in the vein of Child’s Play (though the real horror is the bold Comic Sans he uses for the credits).

Ali: I think there might be an element of mocking there, though, I wonder if that’s relevant only to the subject matter: dissociative identity disorder is a big grey area in psychology and I think it’s probably the most controversial diagnosis around. If the doll had, say, schizophrenia, I think Gibbons’ delivery would be very much considered sarcastic, but I think it’s a lucky strike that it was DID. Also, there’s no such thing as a perfect treatment, and if there’s an intervention worth calling out for its absurdity it’s probably psychoanalysis (though that’s a discussion for another, more boring roundtable).

Ivan: Gibbons gives another very committed performance here that recalls his other piece in the program, The Phony Trilogy. I think though that what makes this a slightly more interesting work from the perspective of performance is exactly the analysis/analysed split that Ali brought up just a little earlier; as an audience, there is enough ambiguity in the set-up that we are a little unsure about how to treat what Gibbons is doing here. I think it resonates as well with what McGuire was doing in I’m Crazy…, which is calling into question how much power the character has over themselves and the role they’re inhabiting. Though Gibbons’ performance is interesting on that level, I actually found the slasher-film-in-miniature ending the most entertaining part of the work, a segment that exploited the obscurity inherent in the format (both frame size and the heavy b/w contrast) to the fullest effect.

Conor: The final Animal Charm short in this set is Lightfoot Fever, which is only one of two Animal Charm shorts available on YouTube. Their full collection is on Fandor, as I mentioned earlier, but it is a shame that their stuff is not more easily accessible, particularly in the modern internet landscape, where it would probably find an audience in fans of Tim and Eric. This short itself is a re-edit of a video where Jim Bailey dances to the iconic “Fever”, a song whose stature comes from its various cover versions. That lost sense of true musical identity is mirrored in the visual disruption Animal Charm inflict on Bailey, which comes in the form of the removal of pauses and insertion of nature documentary footage of sentient deer and rabbits.

Ali: Hendricks’ point about Animal Charm upending television to make it “babble like a raving lunatic” really resonated with me, and I think Lightfoot Fever is a great distillation of this thesis. In it, television (or advertising, more broadly) exists to send us into a sort of emotional frenzy, forcing a set of morals or emotive schemas upon its audience that feel out-of-sync; it’s not until you dissect the thing that you can see how disjointed it really is.

Ivan: Lightfoot Fever sees Animal Charm use an even more limited amount of source material, this time just using a televised performance of “Fever” and a handful of clips from their trusty nature documentary archive. As Conor points out, they cut out the gaps between lines that otherwise structure the song, which has the effect of removing the natural rhythm of the piece and replacing it with something more choppy and disjointed. I think this makes the choice of such a well-known and well-covered song a particularly effective one, as we are so accustomed to its original arrangement that these reconfigurations become exceptionally jarring. The insertion of the nature documentary clips was quite soothing here I thought, countering the troubling disruption with something a little less sinister.

Ali: Probably the most visually dynamic of all the pieces in this collection, Cardoso Flea Circus is a neon-Technicolour channelling depiction of a very literal flea circus orchestrated by our magnifier visor clad ringmaster, Professor Cardoso, Queen of the Fleas. Her hand is seen constantly prodding, propping and jabbing the fleas into their performances. The sound editing, particularly in the ‘Los Dos Mosqueteros’ and ‘Sir Fleamund Hillary’ sequences, is bloody stellar. Combined with the ever-present hand of Professor Cardoso, it gives a very real sense of the reality of what we are watching: that this is just fleas responding to external stimuli. In this sense, Cardoso Flea Circus feels like a lampooning of the kinds of media we see chopped, changed and satirised throughout American Psycho(drama): a statement that it’s all staged.

Conor: God, this one was unsettling. The all-seeing human eye and garish, giallo-inspired lighting frame the carnival novelty of the flea circus as global spectacle – the various categories of performance and games range from the amusing (‘Brutus, the Strongest Flea on Earth’) to the sickly (‘Flea Feeding’). It’s interesting that you see its strong link to the rest of the program, Ali, considering it was only added to Hendricks’ curated collection in 2015 after the removal of a somewhat confronting Anne McGuire short about the female body. There’s definitely a performativeness to this short, which engages with human identification, but I feel that the lack of human representation itself separates it quite distinctly from the rest.

Ivan: Yeah I think unsettling is the word for this one, and you two have described the visual language that produces that well. It makes for an interesting addition thematically, just because the very concept of a flea circus is one of the most absurd and contrived forms of entertainment that I can think of — it’s literally just prodding tiny bugs so it looks like they’re doing stuff. Read into that a satire of entertainment in the era of mass production if you like. Me, I’m going out to save some fleas.

Shorts Discussed

Stuffing (dir. Animal Charm, 1998)

Control Corridor (dir. Halflifers, 1997)

The Phony Trilogy (dir. Emily Breer, 1997)

I Am Crazy and You’re Not Wrong (dir. Anne McGuire, 1997)

Ashley (dir. Animal Charm, 1997)

Actions in Action (dir. Halflifers, 1997)

The Telling (dir. Anne McGuire, 1998)

Multiple Barbie (dir. Joe Gibbons, 1998)

Lightfoot Fever (dir. Animal Charm, 1996)

Cardoso Flea Circus (dir. Maria Fernanda Cardoso and Ross Rudesch Harley, 1997)