Essential Independents is a new festival, hosted by Palace Cinemas, that will screen both bold new voices and old grandmasters of American independent cinema. Ahead of its launch this week, we spoke to artistic director Richard Sowada about weaving the two in a festival environment, as well as the general state of Australian distribution.

There’s quite a few films in the Essential Fiction section that have big-name actors (like Richard Gere and Natalie Portman) and have already had their US theatrical runs, yet you can comfortably say that your festival has their Australian premiere—they’re not even on Netflix or iTunes. Do you see the program as a kind of corrective to gun-shy local distributors?

That’s a really good point. One of the things is that festival programming and broader programming at cinemas is not based on the next good idea, it’s based on the last success. It’s a constantly backward-looking industry where it’s… I wouldn’t say formulaic necessarily, but it kind of is. It’s really gun shy and very risk averse. What I’m hoping with a program like this is that, with some of these titles, that they can actually demonstrate that there’s an audience there for them, and that distributors and exhibitors would then go “oh OK, I didn’t realise, there is actually an audience for this”, and hence, slowly change the attitude and our buying patterns.

But you know, one of the things that I’ve found for many years now is that distributors and sales agents—and funding agencies are the same as well, God love ’em—is that: if it’s an idea that they’re not familiar with, or an audience that they’re not familiar with, the word that they will use straight away is “that’s too niche.” I’ve come to learn in my own way that niche doesn’t mean “small”, it means “you don’t understand”. That’s what it means, I think. Hopefully with some of these titles—certainly something like Mapplethorpe, the Robert Mapplethorpe documentary… I mean, far out, that’s a niche life, but it’s proven to be one of the most successful films in the program! It’s selling so well. So the answer is yes, I’m hoping that something like this will make people in the business go “oh, OK, these films can actually work.”

You talk about how you want the program to be more forward-thinking and not rely on old ideas, but at the same time, with regards to programming the retrospectives, there’s also an inherent focus on tracing the influences on these new films. For example: you have paired Cruising with Interior. Leather Bar, and Film with Notfilm. What value do think lies in using the festival environment to trace those influences?

Well it’s very important as a curator. There’s two things here, programming and curation. This, I like to think, is a very strongly curated program. When you’re curating, whether it’s a photographic exhibition, whether it’s painting and visual arts and that sort of thing, the frame is a very important thing; the frame to make the pictures sing in a different kind of way, and the angle that you put the light on the picture gives it the certain sheen that you want it to have, or the certain highlights. Building in the retrospective titles, they do provide a journey through the trajectory of emerging independent cinema and they put a frame around the contemporary works as well, and say “here are the influences for these kind of things.”

Just like the original works—some of these retrospective works, they too had their roots elsewhere before then. Jim Jarmusch just didn’t invent Stranger Than Paradise, Kathryn Bigelow just didn’t invent Near Dark, Kelly Reichardt just didn’t invite River of Grass. You can see the films that influenced them in those films. You can see the influences of those films, like River of Grass and Stranger Than Paradise, in the contemporary films that are in this program as well.

A big part of it for me was to deliver a continuum, to get a real sense of journey through it. You have to respect the traditions of cinema, whatever nationality you’re looking at. That’s what these contemporary film-makers do. You can see the work of the masters in their work—not that they are masters particularly, but you can see that they’ve really tried to learn. Those learning experiences are very much in this program in those early works. I like to think that journey is very circular in this program.

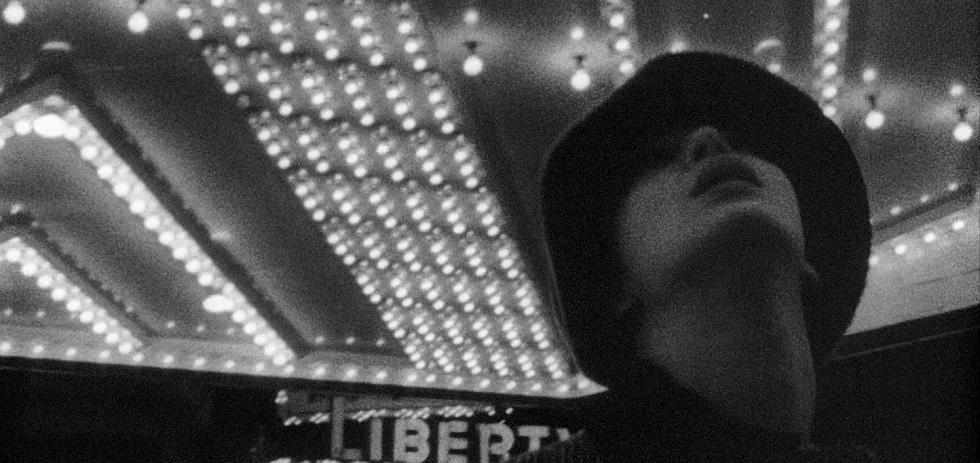

It’s interesting to note that the poster’s key image is from John Cassavetes’ very first film as director, Shadows, and you talk about how there’s a sense of urgency and no holding back with those early films. Why did you want to, at least in that way, ascribe the festival’s identity to early, urgent, no-holds-barred films like those?

Well again, it’s part of the continuum. These things don’t just come from nowhere. People think that skateboarding was invented yesterday. Well actually no, it’s been around for a long time. Part of that is to really bring the concepts and the films back to the roots. I don’t know about you, but with me, when I first got involved with loving movies at a very young age, you fall in love with what you can access, and then when you start to discover the roots, the deeper you go into it, the more things you see, the more down the hole you go and the more you go into the actual roots, the more beautiful the current things are and the more beautiful the older things are as well; the more surprise there is. “Oh, wow, I never knew that, I never knew that. I’ve never seen anything like that before.”

When you see something like Pulp Fiction for instance—which is great independent film, I love it—but once you go into the roots of independent cinema, you can see so many films in Pulp Fiction and it makes Pulp Fiction a much more enjoyable film to watch once you can see, say, Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing in it. That’s right in Pulp Fiction. Also, Kiss Me Deadly, the great film noir film, that’s right in Pulp Fiction. It makes Pulp Fiction more fun, but it also makes those other films not just more fun but more important as well. So, it’s a really important thing to understand the roots and to experience the roots because if you’re a filmmaker, you don’t have to make all the mistakes, you don’t have to reinvent everything—the masters have already made the mistakes for you! Tarantino learned that those mistakes, those wins and those losses, they’ve already been made by somebody. All you need to do is really look at them.

It’s such a double-edged sword these days in terms of people my age, for instance, being able to go to Netflix or other streaming platforms and find those influences you talk about. They’re easier to access but they’re harder to access, because there’s certain gatekeepers in place.

It’s a funny thing. Putting a program like this together, there were films in the Retrospective components that I wanted to put in but I just couldn’t get. They’re just not available. Either no-one owns the rights, you can’t find out who actually owns the picture, [or] you can’t get a good-quality reproduction of the film. You can get like 35mm but you just can’t show 35mm anymore, except for a few places like the Brisbane Cinémathèque up there in the Gallery, or down here at ACMI and very few other places. Many of these titles, they’re almost lost.

Just to bring it back to modern-day films and specifically the experimental films like Sixty-Six or Machine Gun or Typewriter?, in terms of tracing current movements or attitudes, what do you think those films reflect?

Again, they go right back to the roots. Machine Gun or Typewriter?, the guy who wrote that, Travis Wilkerson, he’s actually quite a socialist film-maker, very politically motivated. He made a documentary—and this was my first experience with him, probably ten years ago or so—about a Cuban revolutionary film-maker called Santiago Alvarez. If you have time, look at [Alvarez’s] short film Now—that is fucking incredible! It’s all found footage. This is during the height of the Cuban Blockade in the 60s. There was no raw footage, [so] this guy Santiago Alvarez, he made found-footage critiques of international politics, you know, snippets from other films that he edited together because he couldn’t actually shoot anything. I got introduced to that world of found-footage film-making through this guy Travis Wilkerson, so Travis’ roots go right back to the 50s and 60s.

And then [Travis] spits out this film now, Machine Gun or Typewriter?, which is a very political film as well, in which there’s a lot of found footage, and a different kind of political agitation. I don’t know how much you know about that kind of style, it’s called agitprop. It’s really agitative, and again, very urgent, but it’s using every tool that he has at his disposal to tell his story. It’s not just “pour it all into the cauldron and stir it up”; it’s a very precise use of media, and that’s a very contemporary thing… although, I’ll correct myself: with that: it’s not a contemporary thing. People like Santiago Alvarez also had a very powerful and deep understanding about the power of media and how media actually works, and that’s what Travis has done with Machine Gun or Typewriter?.

I asked earlier whether the festival was an antidote to conservative theatrical distributors but it’s pretty clear that the Australian festival environment is facing its own conservatism as well, with Federal funding getting scaled back and digital distribution dominating. Considering those modern challenges, what opportunities do you want to provide at Essential Independents for new directors, like Anna Rose Holmer for instance?

Something like this is very important for her. The Fits is her first feature. It’s an amazing movie. It really is different. It’s so fresh in its style, it’s really easy for audiences to get a hold on, it’s not alienating, so any audience really… it’s a really beautiful film to watch, but it’s just different in the way that it tells a story. So for her to come out to Australia and represent her film, that’s a big thing for her.1

She’s on the circuit now, and the circuit is a very difficult thing to work and to understand, it’s very demanding, but the beauty of it for her is that she gets to look at people like you in the eye when she’s screening her film and talk to you about what you think about her film, and what you think about cinema. That’s a really important thing, and the more film-makers—Australian, American, French, Icelandic—can interact with audiences and look at them square in the eye and really talk about the world of cinema and the art form, the better off they will be personally and the better off everyone will be, because it’s very easy to be removed by many many layers of the industry. It’s a very dense, thick industry. It’s very easy to be removed, and the more you’re in it, looking at people in the eye, the better off everyone is in the industry and the more free it becomes.

The Essential Independents festival runs from May 17 to June 8 at Palace Cinemas in Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Brisbane, and Adelaide. You can find out more at the festival website here.