In announcing “I’ve never quite trusted films about film”, Ross Lipman begins Notfilm—his film about a film, specifically the 1965 Samuel Beckett short film called Film—with a relatively neurotic self-assessment. “Art shouldn’t be about art. It should be about life, and it should speak about life,” he continues, before quickly pushing back: “or so I told myself, as if they were somehow distinguishable.” Choosing to open on this specific observation—more personal than analytical—establishes the documentary (or “Kino-essay”, as Lipman describes it) as both an exploration of Beckett’s Film and the processes and visions that inform making such a work; as well as the implications of making the work we go on to see.

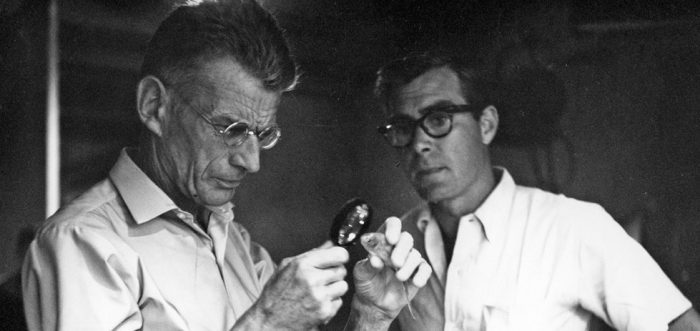

Film remains Beckett’s only screenplay, and has frequently been read as one of the more divisive works from a writer with an already divisive oeuvre. On one hand, Beckett’s work was lauded by academics like Deleuze, who called it “the Greatest Irish film”, while others castigated it as bloated and non-sensical, including Buster Keaton, Beckett’s lead. The interactions with Keaton are central to Lipman’s analysis, as we’re shown two stringently different artists clashing in their views of how films should be made, with Beckett’s approach consistently in contrast with the more traditional one of Keaton. Conversations are lifted from rehearsals and placed in the final scenes, and in documenting this process Lipman navigates a unique tension between two artists who had irreconcilable views of filmmaking—yet as we watch, the two end up making Film together, despite the particularities of Beckett’s vision frequently frustrating Keaton.

Choosing to make this “Kino-essay” is a choice by Lipman that pays off throughout. On one level, Notfilm could have played out as a more standard documentary focused on the anger and tensions that was occurring off-screen between the crew, the media, and critics. Instead, Lipman’s focus is how these tensions played out on screen, and the result is far more rewarding—one that manages to pry into the nature of collaboration and conflict. As well as excerpts of the final product, Notfilm fills itself with shots of rehearsals, unused takes, and other parts of the process, and in these Lipman frequently interjects with his calm yet cuttingly insightful narration, effectively managing the consistency of the work as a “Kino-essay”.

The nuance in Lipman’s work is refreshing, in that he never tries to argue that Film is a masterpiece, instead making a case for the extensive relevance of the work. He maintains that Beckett was a genius, whilst throwing that thesis against the backdrop of the director’s immense inexperience in a filmic medium, tracing how the interplay between these facets resulted in “a flawed work that speaks to more than its surface”. His admission is that Film is a flawed work, but one that represents a palpably ambitious and testing time for both Beckett and Keaton. Lipman is simultaneously able to analyse the work itself and use it as a mid-point between two individuals, reflecting on the respect positions they inhabited in society at the time.

With the same black-and-white colour scheme and 4:3 aspect ratio throughout, there’s a strong sense of aesthetic coherency throughout Notfilm. This isn’t a short work at over two hours, and there’s a certain cinematic patience in the time and space in which Lipman’s analysis evolves. This final product emerges as a thorough and insightful reflection on artistic difference, the complexities of different mediums, and the ability of a work to be chaotic, messy, a failure, and brilliant. Stripped back and faithful to fulfilling this idea of a “Kino-essay”, Lipman’s work is a visual dissection of the process of filmmaking, and a comprehensive look at a very specific period of Beckett and Keaton’s careers. For those with a strong interest in either individual as well as those familiar with Lipman’s previous work, Notfilm is a slow, intricate and deeply worthwhile look at Beckett’s incredibly short screenwriting career.