Lewis Klahr’s Sixty Six is a prodigious summation of the director’s last several decades working as an experimental filmmaker, comprised of a series of discrete chapters created between 2002 and 2015. Combining a dizzying mastery of artisanal collage techniques that Klahr has made his own, Sixty Six is also a compendium of many of the director’s thematic and historical pre-occupations, which are floated dream-like across the twelve chapters. As in his other films, the detritus of mass production and mass cultural forms of post-war America, particularly of the 1950s and 1960s, come together in a work that demonstrates a nostalgia for a bygone era as well as a cryptic treatment of its unspoken, perhaps more sinister undercurrents. Klahr revels in the popular visual iconography of this period of American history, evoking a complex chain of emotional and thematic associations — plays of power and control, romantic traumas, and everyday melancholia— that act as the film’s pulse and loose organising principle.

Over the years, Klahr’s filmmaking practice has remained remarkably consistent, working almost entirely alone on his films in a labour-intensive fashion. For the most part, Klahr has worked with cut-out materials, which he manipulates by hand and in turn films himself.1 For someone who is by no means an expert on this particular branch of avant-garde, the closest visual analogue that I can think of is the work of someone like Harry Smith, and his sui generis experiment Heaven and Earth Magic from 1962. Even still, Klahr displays a certain level of dexterity and layered density in his work that goes beyond Smith’s cosmic foray into cut-out animation.

What arguably takes these works beyond the realm of cut-out animation specifically — a term for which Klahr has expressed a certain distaste in reference to his works2 — are what we might call “extended” camera techniques, such as smudging the camera lens, or accentuating the depth of image through the superimposition of cut-outs with three-dimensional objects. This in my mind puts him more in line with other extreme low budget filmmakers such as Paolo Gioli, whose DIY camera manipulations similarly bring to focus the materiality of both the apparatus and the objects it films.3 Though Klahr has worked with the more prosaic and low-budget formats that have historically been associated with avant-garde and experimental filmmaking — namely Super-8 and 16mm — the director made the switch to digital video in 2007, a format to which he has remained faithful ever since.

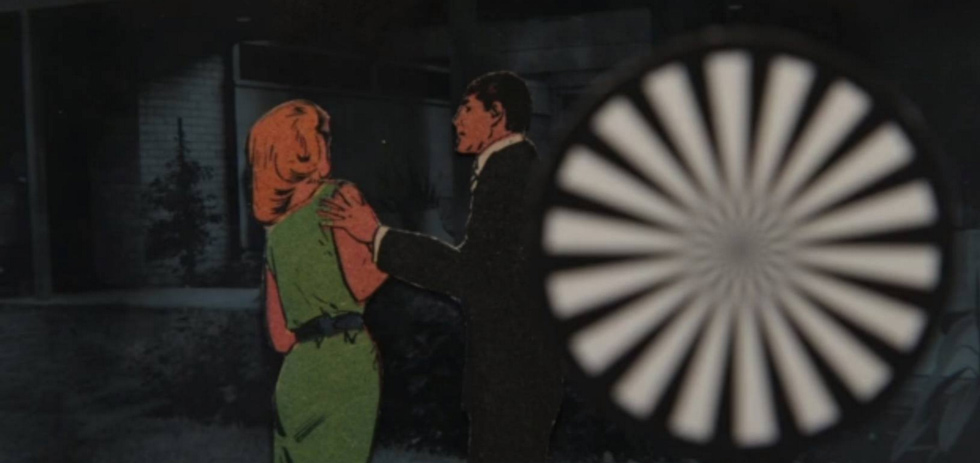

In Sixty Six, Klahr plumbs the depths of an archive that has been the foundation of his distinct visual lexicon: images from mid-century advertisement, comic books, Pop Art figures, Life magazine, and architecture catalogues populate a distant world that seems straight out of a pulp fiction novel or B-grade noir. These “ephemeral talismans of American commerce and popular culture”4 interact in a kind of stop-start choreography that exists at a fascinating mid-point between visual abstraction and elliptical narrative forms. Indeed, part of what makes Sixty Six so interesting is the way that it vacillates so freely between the two poles of narrative and abstraction, inviting the spectator to engage with the film instead through associative, pre-logical patterns. At times, the film’s comic strip characters seem to be fully embroiled in the intrigues that are hinted at in the speech bubbles above the frantic-looking figures of Rauschenberg’s paintings. But these moments — where actions and gestures might be assimilated into a comprehensible chain of events — comfortably cohabit sequences that we’d normally consign to having purely plastic ambitions.

The structural patterns of Klahr’s sound design are similarly complex, with silence a real rarity amidst the heady mix of popular music (Leonard Cohen, a late-period Miles Davis improvisation), music composed for the film, and snippets of sound art. The film’s fourth episode, Erigone’s Daughter, is something of an exception in this regard; Klahr layers over it an excerpt of dialogue from what sounds like a radio play or a film. Here, the somewhat cryptic off-screen references to criminal activity and general film noir subterfuge — a woman offers a man $100 to do a “job” for her — fleetingly overlap with Klahr’s on-screen collage of distressed women, suitcases, motels and prescription drugs.

Elsewhere, in the comical episode Saturns Diary, Klahr cuts together snippets of everyday sounds (cars pulling into driveways, alarm clocks, dripping faucets) into a piece that seems to identify the Roman god of time, and plenty as an older white man in a suit and tie. His mundane day-to-day existence, evoked by a recurring close-up of a calendar, is populated by consumer goods and flits between scenes in upscale modernist apartments.5 There are hints at a romance that disrupt the otherwise uneventful life of the god Saturn: a woman begins to enter into the frame, they are posed in the shot with their backs turned to the camera, another man is seen reaching his arms out in distress. The numbers on the calendar are blurred by what looks like Vaseline smeared across the camera lens, we hear snippets of a string score that sounds like Bernard Hermann circa the Vertigo soundtrack.6 Klahr ends the sequence in full abstraction: a flashing cycle through colours of the light spectrum. Saturn disappears into the colour wheel.

While this description of the above sequence can only partially account for its full visual and aural complexities, it does speak to what the best passages in Sixty Six are capable of evoking: an associative reverie that gives life and emotional weight to these distant cultural objects. Klahr’s film is full of these moments, and this undoubtedly accounts for how affecting the experience of watching Sixty Six often is. More than just a work of exceptional technical brilliance, Klahr’s film is a moving personal engagement with an otherwise remote archive of images.