It’s the nature of collective interest in minority rights to wax and wane, but every so often, we’re reminded of their continuity in spite of their social latency. The fiftieth anniversary recording of Johnny Cash’s 1964 concept album Bitter Tears: Ballad of the American Indian is one such reminder of the historically sidelined fight for Native American rights. The appeal of We’re Still Here seems specific – a look at the rerecording of a little-known Cash album, based on director Antonio D’Ambrosio’s book about it – but the film’s focus on the history of Native American struggle lifts what would otherwise play out like an extended behind-the-scenes featurette.

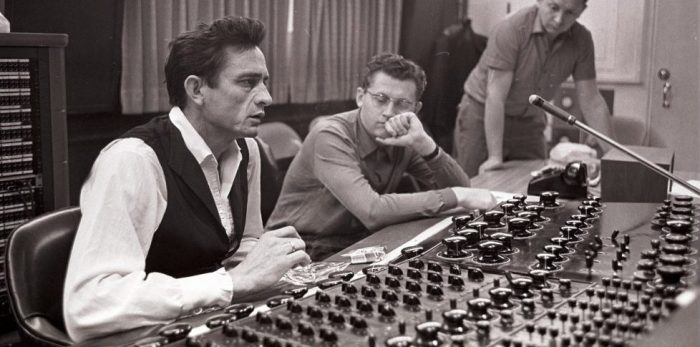

Bitter Tears was signed off on by Columbia records as a half-hearted indulgence of perceived activism, following the commercial success of “Ring of Fire”. The result was a collaboration between Cash and the relatively unknown folksinger and songwriter Peter LaFarge, whose influence D’Ambrosio’s interviewees unfailingly reiterate. The film opens with Grammy-winning producer and musician Joe Henry in voiceover, reading Cash’s letter to Billboard Magazine from May 1964, indicting their refusal to advertise or review his album. This accusatory refrain in Henry’s rough-edged Cash imitation sustains a confrontational tone throughout the film. Cash’s urgency becomes our own, as we mirror his demand to know why. Why were Native American rights denied airtime? The Civil Rights Act was enacted in July 1964, but why were its supporters unable to see the very clear parallels between seemingly disparate minority issues? This undercurrent of indignant inquisition becomes the film’s backbone.

D’Ambrosio’s occasional spotlight on specific issues (like the Kinzua Dam construction on Seneca land) steers the film away from being mere Cash fan-fodder to a comment on music’s capacity to provoke dialogue. D’Ambrosio stresses the idea of Cash giving a voice – lyrically, musically – to the Native American community, in the tumult of the impending presidential election. In the 1930s, Cash grew up in poverty alongside native communities in Arkansas. While the New Deal resettlement programs improved his family’s living conditions, he continued to witness the stark destitution of the native community. In 1964, his commercial reputation finally provided a platform for his lifelong advocacy, meted out with palpable frustration.

The new recording features a host of acclaimed country artists, including Mohican musician Bill Miller, and Onedian singer and guitarist Joanne Shenandoah, both of whom stress the importance of Cash’s willingness to pull these issues into the mainstream. There’s a particular point of pathos in the case of Ira Hayes, the Pima Native from southern Arizona who rose to fame as one of the US Marines in Rosenthal’s 1945 photograph “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima”. Cash and LaFarge’s “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” details Hayes’ postwar alcoholism and his eventual death from exposure and alcohol poisoning outside an abandoned hut. D’Ambrosio captures a collapse of mythos as Cash’s sings Hayes’ painful demise, playing over an iconic image of American triumphalism. The album is rooted in such incongruity – the admiration Cash held for the Native American community, and the utter lack of respect they received from mainstream America.

D’Ambrosio stresses that the album isn’t archival, that the work “asks to be held up”. Though the interviewees’ emphasis on retrospective power becomes repetitive, they make a good point. As musician Rhiannon Giddens notes, there is a tendency to characterise Native American struggle as an elegy to a lost community, but the revival of Bitter Tears found in We’re Still Here is a reminder of persistence. Though brief at 50 minutes, the film doesn’t strive to be more than it is – a half-century celebration of the epiphany that should’ve, but didn’t, come in 1964.