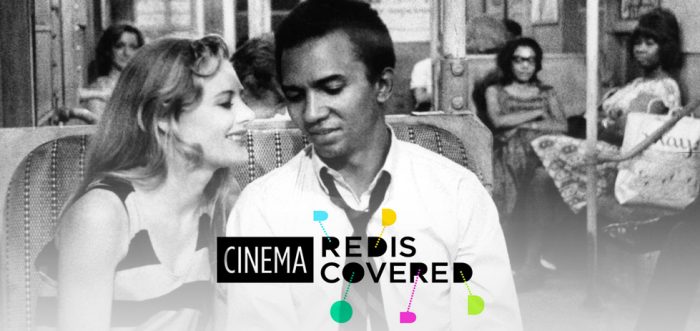

With the launch of the inaugural Cinema Rediscovered, an archive and classic film festival in Bristol, England, we are presenting a series of pieces on the screening program. In the first of these, Tara Judah, a Curator for the festival, looks at Anthony Harvey’s gripping Dutchman, screening in Cinema Rediscovered’s Black Atlantic Cinema Club strand.

I can’t remember the last time I sat in a cinema where the audience collectively gasped with shock and in horror, but Anthony Harvey’s screen adaptation of Amiri Bakara’s play Dutchman is the single most explosive film I’ve ever seen.1

The film, almost twice as long as its source material, yet still a succinct fifty-five minutes in duration, is primarily about race, societal fear and broiling anger – all products of Baraka’s dense and igniting dialogue. But it’s also a character drama of the highest order and it features one of the most impressive and terrifying performances committed to film.

Lula, played by the convincingly psychotic Shirley Knight, is a clear physical inspiration for Laura Dern’s much softer, endearing and yet still slightly deranged character of the same name in David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990). Knight’s Lula is the mould for a sexy middle-class white-trash all-American mix-up. Riding the subway, looking for a good time on a stiflingly hot summer’s day, Knight plays the part with a physicality that is mesmeric and horrifying. She throws her body around the empty train carriage in a sort of hypnotic mating call to entangle and entice an unsuspecting black man. Clay, played with subtle reserve by Al Freeman Jr., is minding his own business, whose error is the brief act of catching the predatory eye and engaging with the exaggerated to-be-looked-at-ness of Lula.

Though other people do eventually appear in their carriage, the uncomfortable and shocking line of conversation stems from its binary engagement; woman against man, white against black, power against powerlessness, control pushed up against forced submission. Knight is so sublime in her performance that she transcends acting and becomes the pure invocation of hundreds of years of bigotry, injustice, hatred and sadistic control. And while Freeman Jr. brings a contrasting believable caution and certain naiveté to Clay, his outburst is passionate, inflamed and guttural when Lula pushes him past his limits.

Learning, in retrospect, that Knight was the driving force behind the production of the film goes some way to explain her truly brilliant performance as Lula – the film is only as impacting and explosive as it is because of the utter believability of her uncontainable performance. But her intermittent outbursts are also enhanced by the perfectly fitting image and sound given to this troubled yet fitting production story. Knight, who was apparently impressed by the L.A. stage play, bought the rights and, in partnership with her then husband Eugene (Gene) Persson, set about trying to get it on screen. Despite the story being set in the New York subway, they couldn’t get permission to film there – the content was far too explosive for a US market, no one wanted to touch it. So, they took it to the UK and shot it in a London film studio for $25,000.

Curiously, they appointed Anthony Harvey as director–and this was his debut. 2The other baffling, frightening and dynamite element is Baraka himself. His life story and transitioning views cast a heavy shadow over the text; at the time of Dutchman he was divorcing from his first wife, a white, Jewish woman named Hettie Cohen. Also around this time, Baraka was also becoming politicised with the Civil Rights Movement, after a period where Baraka and Cohen were involved with the Beat Poets; they published the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac through Totem Press. One thing that is for certain is that Dutchman is a call to arms for young black men. There is a potency to the relationship between a black middle class man and a white middle class woman that hits on not only sore points of history but that also throws a grenade into the heart of the fears of people on all sides of the melting pot racial equation we understand as the US.

Aside from the occasional shot of the dark, dank underground tunnels—with flickering and unkind fluorescent lights, shining unkindly on the true dirt of American race relations—Dutchman takes place entirely inside a single subway carriage. The cinematography (from Gerry Turpin) is stunningly claustrophobic, occasionally widening out to reveal the carriage as either emptiness in empathy from absent onlookers of exploitation (i.e. no one is there) or to show the complete terror and disengagement of others when atrocity is taking place right before their eyes (i.e. as the carriage becomes full it stays empathetically empty).

Dutchman is an unparalleled experience born of anger and hatred, yet it is marked by its passion and determination to cause pause for thought as it shocks and surprises. Painful and extraordinary stuff.