The 69th iteration of Locarno Film Festival marked the first covered on the ground in Switzerland by 4:3. As a festival, Locarno been widely viewed as one of the most experimental, auteur-driven, and carefully curated festivals of its size. Whether it was last year’s Golden Leopard winner in Hong Sang-Soo’s Right Now, Wrong Then, Pedro Costa’s Horse Money, Albert Serra’s Story of My Death, Lav Diaz’s From What is Before, or the late Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie, the few films that have screened in Locarno’s Concorso Internazionale (Official Competition) and ended up playing in Australia have often sat among our favourite works in recent years. This year, there was a noticeable absence in the same amount of bigger names in the competition, and this was refreshing to see. While many of the filmmakers were established in their own right, Locarno69’s competition emerged with a clear interest in building foundations for the future of cinema.

Ralitza Petrova’s Godless, which took out the Golden Leopard this year, was also the director’s feature-length debut. A stark portrayal of lingering depression in Bulgaria, Petrova’s film is an incredibly accomplished debut. The shots throughout the film wrap the film in a palpably bleak atmosphere, with phenomenally nuanced performances that result in an exhausting and overwhelmingly powerful work. The world that Petrova paints is awe-inspiring in the brutality of its realism, as well as ease with which it drags its audience into that world – emotionally, physically – is very likely one of the reasons it took out the top prize. There are clear films within the competition that were always going to have a strong festival run, and while awarding first-time features isn’t remotely some feature exclusive to Locarno, it’s a reminder of the influence festivals can still hold in propelling films and directors – and the way in which approaches to curation can shape that structure.

Concorso Internazionale

Jeremy Elphick:

While Ralitza Petrova’s aforementioned competition winner Godless was a clear highlight, João Pedro Rodrigues’ latest, O Ornitólogo (The Ornithologist), emerged early in the festival as one of the strongest films at the festival. While the work had clear marks of the style Rodrigues has refined over the past two decades, it managed to distinguish itself as one of the his most inventive and dense films to date. While previous Rodrigues films such as O Fantasma or Two Drifters are laden with a clear personal element, there’s a more magical sort intimacy that takes place in The Ornithologist. Built on his early ambition in life to be an ornithologist, Rodrigues goes on to paint a filmic landscape that re-contextualises the story tale of Saint Anthony, the eroticism of religion, and the AIDS crisis in Portugal; all whilst making a stunning case for the transformative power of cinema.

Thai director Anocha Suwichakornpong’s sophomore effort Dao Khanong (By The Time It Gets Dark)—her first since 2011’s Mundane History—was another clear highlight in the competition; a film explicitly reflecting on the process that informs filmmaking, whilst engaging with the broader context and world that shapes this. From reflections on the political past and present in the country, meditations on the saturation of technology and simulation in our lives, to the intersections between capitalism and the existential, the scope of Dao Khanong is sprawling yet focused, with a profound approach to form.

Sitting at the other end of the festival was Katsuya Tomita’s Bangkok Nites, a surprisingly expansive and complex work that used its 3-hour runtime to burrow deeper into itself, pursuing and revealing the intricate and unique relationship Japan and Thailand share. From an initial focus on the sex trade in Bangkok, Tomita’s work quickly changes pace as he ventures to the Isan province, dealing with the ghosts of the past and the lingering effect of colonialism in the region. The oscillation between these parts, both in the pacing as well as the aesthetic, creates a certain film within a film, with clearly distinct sections.

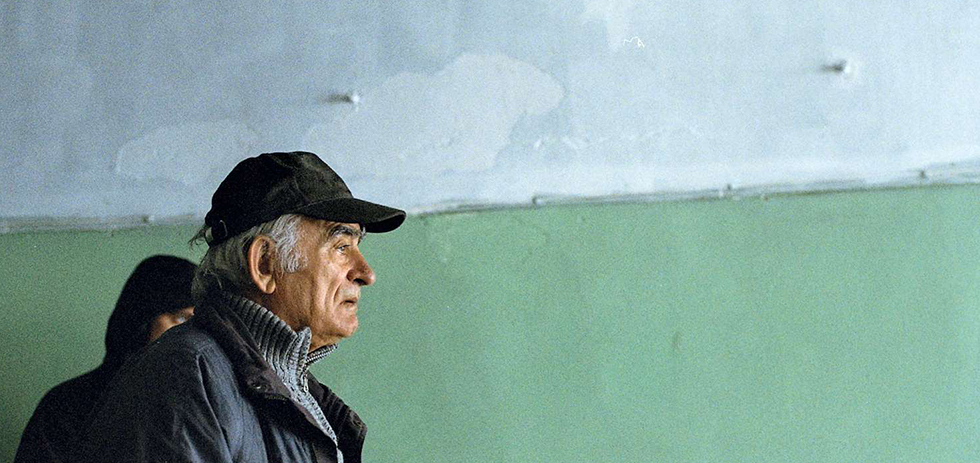

Of the remaining films: Radu Jude’s Scarred Hearts was a spectacular meditation on the life of Max Blecher, with an inherent focus on the potential of cinema, reasserting the director’s place as one of Romania’s most captivating directors; Akihiko Shiota’s Wet Woman Woman in the Wind offered a crisply-shot, modern take (and inversion of) the Japanese 70s pink film sub-genre of the roman porno; Jan Matusyznski’s The Last Family saw the long-awaited debut feature from one of Poland’s most promising directors.

Annabel Brady-Brown:

Angela Schanelec’s eighth feature, Der traumhafte Weg (The Dreamed Path), is a glorious existential sucker punch. Plot-wise, this wonderfully strange, narratively elliptical work from the Berlin School filmmaker moves between two worlds: a young couple’s holiday fling in Greece in 1984 that melts, unidentified, into the lives of an older couple who are separating in Berlin, thirty years later. Shot with chilling formal rigour, Schanelec manages to express everything—heroin addiction, the death of a parent, extinct hopes, solitude—through an intense Bressonian framing of mostly hands, feet, and torsos. The film builds its own trance-like rhythm while cold shouldering on-screen drama. Dialogue is stilted, sparse, each figure wrapped into themselves, and other than a cathartic burst of Flume’s remix of “You and Me”, most of the film passes in silence, stasis. When a young girl breaks her arm we only see her carry the ladder to a window and then her body resting on the floor, as if sleeping. Magnified by these gaps, the gestures of Schanelec’s lonely, aching bodies resonate far longer than any words.

Hermia & Helena is the sixth film by Argentinian director Matías Piñeiro, and the first set outside of his home country. With its action split between a life in Buenos Aires and a fellowship in NYC, Piñeiro’s film sees new friends from the US indie film world (mumble-slacker Keith Poulson, filmmakers Dan Sallitt and Mati Diop) join his beloved ensemble of recurring Argentinian actors and crew. A young woman named Camila travels to NYC to translate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the latest Shakespeare comedy to inspire a Piñeiro adaptation. Part Millennial riff, part po-mo excuse to toy with narrative devices, Hermia & Helena is a freewheeling joyride through the Bard’s classic romance.

Matilda Surtees:

Axelle Ropert’s La Prunelle De Mes Yeux is an unusually self-aware romantic comedy. It’s at its funniest and its most sincere when it takes aim at social and economic failure, inadequacy, pettiness, and loneliness. Touching lightly upon the Greek financial crisis through the Greek identity of the brothers, Ropert seems to reach out directly to a demographic who feel a sense of instability and a fear of impending catastrophe, both political and personal, permeating their lives. While the final romantic scenes perhaps act as the standard fulfilment of the narrative promise of a romcom, they feel gaudy and saccharine compared to the darker strands of comedy. These scenes have less of the enjoyable self-awareness of the earlier humour, almost betraying its premise: the joy and relief is in laughing at the struggle, not subsuming it in a romantic fiction.

Cineaste, Signs of Life, and other highlights

Jeremy Elphick:

Eduardo Williams’ has been making a name for himself in recent years as one Argentina’s most inventive younger filmmakers, as well as one of the most distinct and captivating directors in his own right. With El auge del humano (The Human Surge), however, Williams’ brings together the distinct cinematic style he’s made himself known for in his short films, creating a cohesive debut feature whilst remaining pointedly innovative and experimental. Reusing ideas from his shorts – such as a particular amusing (and largely re-contextualised) scenario where a character is wandering through a village in the Philippines looking for an internet cafe – he builds and coheres 3 shorts, with memorable and alluring transitions throughout.

Wang Bing’s latest, Ta’ang, continued it’s festival one, as one of the director’s—who was on the jury for the official competition—strongest and most focused documentaries to date. Following a group of refugees who Kokang in Burma’s Shan State due to the conflict in the region, Wang tracks their lengthy journey across the border into China, eventually winding up in the Yunnan province. For a director that established himself with a 9-hour epic in Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks, Wang’s entire career has been defined by pushing the limits of the documentary form. Ta’ang continues a trend of intensity in the filmmaking process, perhaps most starkly expressed previously in ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, where the director inserted himself into a mental asylum in China to make an intimate 4-hour humanist opus that simultaneously functioned as a stark indictment of the way in which mental health was dealt with in the country. Wang Bing has established himself as one of the most innovative and uncompromising documentary filmmakers due to this approach to process, and it’s something that he solidifies in Ta’ang as one of his strongest works to date.

A more surprisingly sociopolitical work out of China at the festival was Jia Zhangke’s short The Hedonists – which our own C.J. Prince covered in his TIFF2016 piece. Jia’s film is a brief, fairly comedic look at a group of men who have been laid off due to a factory closure. It follows them trying to find new jobs, struggling to adapt to the changes within the country. While it’s only a short work from Jia, it manages to paint a strong picture of industrial decline, whilst being a concise, accessible, and amusing piece. For those who aren’t in the mood for a 9-hour 3-part documentary from Wang Bing about industrial decline, Jia’s 30 minute short is amongst the best of what the other side of the spectrum has to offer.

Annabel Brady-Brown:

Adapting Albert Camus’ The Stranger (1942) to current-day Poland, Anka and Wilhelm Sasnal’s fifth film, The Sun, the Sun Blinded Me, is a blistering, tight work energised by the resonance of its political agenda. Camus’ famous existentialist Meursault becomes Rafał Mularz (Rafal Mackowiak), a Polish man whose increasing disaffection comes to a head following the death of his mother. Instead of Camus’ shot Arab on the beach, Mularz is induced by the hypocrisy and racism of all around him to murder an unnamed refugee he encounters washed up on the sand, and the film falls into place as an urgent accusation, aided by inventive editing. Mularz is shadowed by the dead man, as if to say: shouldn’t we all be?

Theo Anthony’s debut feature Rat Film is a portrait of Baltimore via its longstanding efforts to combat its rat infestation. Switching in tone between amusing scenes of locals spending their Saturday nights perched in an alley, hobby-fishing for rats, and chilling cartographic histories that illustrate how the city’s urban planning policies have entrenched poverty and racial ghettos, Rat Film is the latest inventive addition to the city-as-protagonist tradition. The lively urban tour journeys with scientists, exterminators (both state-employed and guerrilla residents), and, of course, rats. They become avatars for the downtrodden residents of the beleaguered city and a very real problem. While it falls short of the poetic depth of a work like Deborah Stratman’s The Illinois Parables, Rat Film’s skittish Catherine-wheel structure fizzes gloriously in all directions, occasionally connecting with magic.

Matilda Surtees:

The political, personal and aesthetic projects of Yugoslav director Dane Komljen’s All The Cities of the North align to create a film both persuasive and pleasurable. The film takes us into the rhythms and intimacies of two men living together in an abandoned complex. The cinematography favours subtlety and implication, burrowing into the detail of their lives together: we don’t see the hand that rubs the back, but the rippling shirt. Despite this intimacy, precious and perhaps precarious, their world is not insular: Komljen anchors these two men, their empty complex, their peers, to an international web of collectivity, loss and hope. Komljen uses footage and voiceovers to introduce the audience to the buildings of the International Trade Fair held in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1977, built by a prominent Yugoslav construction company whose projects were largely overseas, and Vila Amaury, a temporary city in the late 1950s built by the workers who were constructing the building for the National Congress of Brazil, and the significance of these historical detours becomes gradually apparent as the film divulges more of the two protagonists to us. Vila Amaury is a particularly potent symbol for what Komljen is trying to convey: a city built by the workers for themselves, the home that they made, was later flooded by the damming of a river – a decision they had no say in destroying their community of choice. The abandoned complex that the two men inhabit is a marker of an economy that has failed them, a society for which they – not working, not paying rent – cannot be ideal citizens. They instead find a community, a society, with each other and their peers. Love replaces labour, alienation to affinity: they are looking for a different way to be, “an empire of equals.”

Interviews

Anocha Suwichakornpong on the influence of Abbas Kiarostami:

“Yes, I know, I still remember the first time I watched Close-Up, on VHS, on a very bad copy of VHS in New York on a TV screen, where I was by myself in the living room. It was a sunny afternoon, I was home alone in my apartment, and I had not expected what it … I had no expectations. I didn’t know what it was going to be about. I had not read anything about the film, and I think actually it was the turning point in the way I view cinema and how it has the power to transform, at least for me. I don’t know if I can change anything in society, but at least for me, it has such an impact on me that I felt, “okay, this is really something that I could give myself. I surrender.””

João Pedro Rodrigues on the religious undertones in The Ornithologist:

“He’s always portrayed with, how do you say, a lamb because he was a shepherd. There’s a lot of religious and biblical mythology in the film. What I try to do is to play with it but at the same time, it’s like religious painting that I think although I’m not a religious person myself, and I don’t have any religious background, My parents were not religious at all so I arrived to religion through painting, I think, and through art, in the writing and the literature stemming from it. I think there’s always this interesting contradiction between how do you paint the saint because the saint is also a man or a woman. It can be also a woman saint but you have to give him or her flesh, and it looks like a real person. At the same time, it can be very voluptuous or very carnal but at the same time, it’s a saint. I like this contradiction between … Even in religious painting like if you think about someone like Caravaggio, the painter, sometimes some of his work was refused. He was commissioned to make several works by the church. They refused his versions. He had to repaint because they were too carnal or, in a way, too blasphemous for the priest’s eyes or for the faith, the church eyes. I like this idea of, at the same time, something that it portrays, a transcendent or being, at the same time, very physical and very … I don’t know, sometimes you feel. You really feel like that you can almost touch that person.

“In a way, religious painting can be very erotic and also religious writing can be very erotic. I don’t know if you’ve read the writings of Saint Theresa of Avila. She describes when she was illuminated. It seems that she’s coming. Also, there’s a very beautiful sculpture in Rome where there’s an arrow that comes and also, it’s almost like she was penetrated. There’s this idea of blasphemy in religion itself, and so that’s what I really try to focus on, because I don’t think also the film … I like to call it utterly blasphemous, but I don’t think the film is blasphemous in the … I hope it is a little bit, but I hope it has some playfulness with that.”

Akihiko Shiota on experience and craftsmanship:

“I said this in my introduction last night, but there was a famous ceramic artist in Japan and when he makes a plate or any ceramic object, he takes three seconds to design it. One journalist interrogated him on it and complained, saying, “If it’s a work that takes so little time to make, why are you selling it for such a high price? You should sell it for cheaper.” The ceramic artist responded, “This work is not made in three seconds. It has taken 20 years of research and effort, plus the three seconds. So it was a work made in twenty years and three seconds. That’s how you should see this ceramic object.” Similarly, I also feel that my film has taken twenty years of research and seven days to write. It has taken twenty years of research and seven days to shoot.”

Ralitza Petrova on the characters in her Golden Lion winner, Godless:

“There is this wisdom about them, or there is something really vulnerable that it’s very, for me anyway, it touches me deeply that it’s … I don’t know; representing the human condition, or the human phenomena of being alive and surviving in this. In some places it’s much harder than others, but as a rule I think life … It’s kind of a strange thing, you know? It’s strange being alive, and then how do you deal with that? I was interested in being very honest with that. Honesty is a big thing for me, being extremely honest without being ironic.”

Katsuya Tomita on the relationship between Japan and Thailand:

“Why did we set much of the film in Thailand? Well, because despite being foreigners when we visited the region, we felt that there was some sort of fundamental foundational connection in particular in these areas. Something we felt that was lost or forgotten by the Japanese we felt existed in these regions. We felt this idea of Saudade with this region, freely by ourselves. Not necessarily something that … How do I put it? We just felt Saudade in that region. What is the secret behind this feeling that we were having? It’s something that we wanted to pursue in the process of making this film.”

Jan Matuszynski on Locarno’s particular approach to curation:

“You know, there’s one absolutely great thing, which I realised yesterday actually. I didn’t have time to go through the program. I’m a fan of some arthouse films. I love Michael Haneke’s stuff. I love a lot of good films, but I’m also a fan of Michael Mann’s films, and Paul Greengrass films, and some other action films also. Because for me a good film is a good spectacle. There’s a definition of both The White Ribbon and The Bourne Ultimatum. Totally different films, but the whole package is… there’s some similarities for me. When I realised that we were screening, the world premiere is between The Conformist, Videodrome by David Cronenberg, and Jason Bourne … I said, “yeah, that’s my place. That’s a place for this film.””

Kristina Grozeva and Petar Valchanov on being influenced by newspapers and real life:

“Yes, yes. It was the real event. It happened many years ago. It was one real railway worker who found millions on tracks, and he gave it back to a group of police officers. Later, the Ministry of Transport … they gave him a new work watch. It also stopped working after two weeks, which is where our story starts from, yes, this point.”

Radu Jude on working with Costas-Gavras and belated influence:

“It’s a strange thing because I was very young when I started to work as an assistant director, I was the third assistant director actually, and one of the few things I was in was Costa-Gavras’ movie, which was shot in Romania. At that time, it was a very powerful and impressive experience … but I felt somehow not very close to his kind of cinema in that moment? But I admired him a lot, and I respected him and he’s way of dealing with people. He’s a really polite and elegant person, but he didn’t impress me then. But now, when doing these two films which deal with history and Scarred Hearts, I started to remember a lot of things from working with him. I would say that only now there’s an influence.”

4:3 at Locarno69