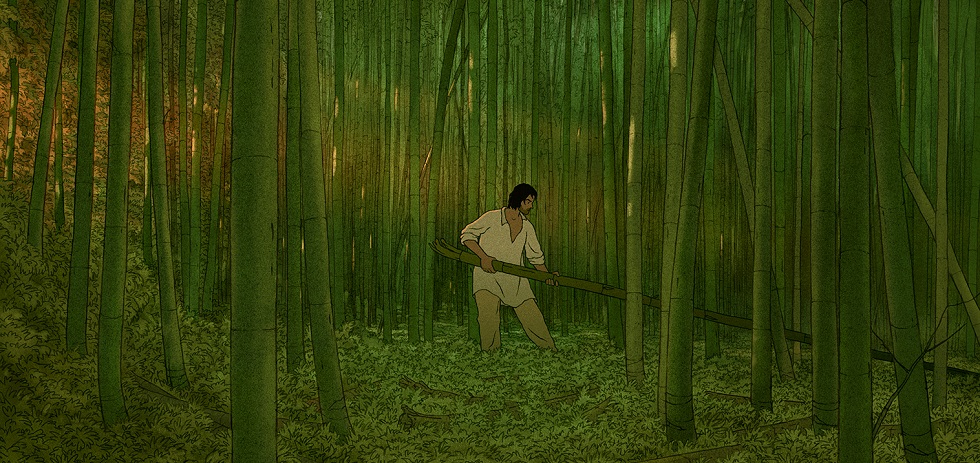

The Red Turtle is a mythical tale about a nameless castaway who, without uttering a word of dialogue, finds his purpose on the shores of a deserted island. It is the first film to carry the Studio Ghibli logo after the company’s ceasing of feature film production, following the retirement of founder Hayao Miyazaki. Making his feature directorial debut with the film is Michaël Dudok de Wit, a Dutch animator revered for shorts like The Monk and the Fish and Father and Daughter, which respectively earned an Oscar nomination and a win. Having earned an Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes with The Red Turtle, he has a great chance of doing the same next year. I spoke to Michaël about what these awards prospects mean to him, as well as the process of finding the film’s striking identity.

The characters in the film don’t belong to a specific country, they don’t speak a particular language, their clothes don’t have any particular symbols on them. At what point in the production did you decide on that universal aspect to those characters?

That was clear right from the beginning. I really like the idea of not telling too much about [the main character]. On the other hand too, we need to have empathy with him but you don’t need to know his background to have empathy, and he really expresses his emotions nice and clearly. I actually like the idea of purity of it, that we don’t know which culture or which century he is from, or which trade he has even.

It’s a beautiful looking film and a beautiful sounding film, as well. I notice as well with many of your short films, there’s music used all throughout, so I imagine the move to a feature must have been a bit of a challenge. How did you and your composer go about bringing together the score?

Actually, the challenge was much bigger than I anticipated because with my short films, I knew which music I wanted to write before I started doing storyboarding. Every time when I had a visual idea, I thought “what would be the perfect music for that?” In every case the music came together, and then the music also set the rhythm and the timing of the film in general. The music was like my muse for the film. And the feature, immediately I knew it was not going to be music from beginning to end. It was not going to be the repetition of one scene like I had done with my short films. It needed more warmth, the film needed to have many parts without music, so suddenly it felt very different. I thought “oh, OK, well, it’ll come to me”. After months it didn’t come, after six months it didn’t come, after years it didn’t come, and I started getting a bit frustrated with that, because I thought I needed again to be inspired by the music, and also to give music to the animators to say “look, there is music you will hear when we see your scene”. That was really frustrating, and people [like Isao] Takahata from Studio Ghibli asked me “so what music do you think you have?” I had a few temporary bits and pieces which were OK, but I always told people, “yeah OK, but we won’t use that, we will maybe use something completely different, we don’t know yet”.

So at some point all the animation was near completion, with not many months left, and I was getting seriously worried about music. The producers immediately started asking dozens of composers to propose something—some new composers, some established composers in France. And one [Laurent Perez del Mar] stood out immediately. He simply did a little melody, which was very emotional, very very pure, and I thought “ah OK, we got him, let’s hope it will work for the film.” At that point I worked in Paris, and he lives in Paris, so we just met a lot, and we talked a lot. I told him “I don’t have an idea for a melody, I don’t have an idea for even a musical style, although I tend to go for the impressionist style, like Debussy. There’s some instruments I don’t want, like for instance, I don’t want any human voices, because I want to emphasise the idea that he is the only human being for a long time.” He did beautiful stuff and it clicked and we got on. You have to have a really good chemistry with composers, because a lot of things you can’t say, you just have to understand each other intuitively, and that I felt right from the first meeting.

But then one day he said to me “Michaël, I want you to listen to this. I won’t say anything, just listen to this music”. He played a piece of music with a female voice on it. It was just an instrument without words, and I went “woah woah woah, hang on, there’s a singer in there!” And we talked about it, my first reaction was “yes, it’s beautiful, but I’d prefer not the voice”, and we listened to it a bit more and I thought “actually, it’s right, it’s really right for this film”. There’s very little ego in her voice—it’s very pure, it’s very emotional, but it doesn’t draw the attention to her too much, so we kept her voice and I’m delighted.

Yeah, I’m delighted as well—that’s probably the single bit of music that I remember most strongly from the film. It lends a lot of power to those moments of transcendence in the film, and notice that there’s similar moments in your other short films as well, whether it’s the Daughter returning to her Father in Father and Daughter or the dot in The Aroma of Tea floating off into the white ether. Where do you think that device of transcendence comes from in your work?

That’s a word no-one has ever used with me before. Thank you very much, I like the word a lot. It’s a natural… let’s say interest. It’s a personal thing, as it is for everybody. I try to express that in film without being preachy, or without even making it into a big message necessarily. It’s more like… if it works for people, then I’m happy. That’s all I can say.

I understand for this film, working with Studio Ghibli allowed you to work under French law, and that was very creatively freeing, but did the studio bring anything creative to the film that no other studio would have done?

Yeah, definitely. I asked them to help me creatively, and they were a bit surprised. They said “hang on, you want our opinions?” I asked them “what do you think of this?” They hesitated a bit, and I told them not only do I want their opinions, I think the film can’t exist without that. Because professionally also, they’ve done many features. Takahata’s not an animator but he has an animation director’s sensitivity and I simply wanted to explore it as much as possible, and their experience. But it’s more than that. Takahata made a film that includes haikus, My Neighbours the Yamadas. We can’t make films like that. No-one can. It’s impossible. Haikus are too pure, too quiet to put into films, yet he did that and it worked for me and I thought “if someone can do that, that kind of support, I want that sensitivity”. He’s very cultured, he’s fascinated by symbols, he’s fascinated by conscious messages and subconscious messages, so I was very interested to talk with him about that. [Toshio] Suzuki had very good intuition. He was a bit more practical but he had a very good intuition too, so I listened to both of them, but Takahata was usually the spokesperson.

There was also another dimension which I didn’t see straight away, but which is now incredibly obvious. When you make a short film, you would explore your most vulnerable parts; your deepest creativity. It’s strong but it’s vulnerable, and especially when you try to be poetic and talk to the finer things. When you make a feature film it’s the same thing, but at the same time there are millions of euros invested in it and you work with a big team. So you are vulnerable to big forces, big egos, ego clashes. People need to defend their position or prove their position. Some people are not creative at all, or don’t understand the creative process—they just see it from a distance and don’t understand it, and they’re quite insensitive about it. Some collaborators are artists and are highly sensitive but also highly possessive about their art, and you have to work with them and get the best out of them. So it’s a big thing for a new feature director like me to work with all these forces and at the same time be incredibly sensitive to my own very subtle creativity, and for that, I literally said at some point to some collaborators “I need to feel the emotionally mature people around me that I can talk with and I can exchange ideas with, [where] I don’t feel like I have to attack opinions or defend opinions, and we can just calmly talk about things”. And Studio Ghibli had that from the beginning. I needed a mature group of people or person, and Studio Ghibli was the first one to just feel like I just need to exchange ideas, and feel free to be vulnerable, so basically they served that role as well.

The film is the first animated feature to win a prize at Un Certain Regard in Cannes, and obviously there is the possibility that it might win more awards in the future, but considering all of what you’ve just talked about with the creative process, what does that kind of recognition mean for you going forward?

Here, I’m very practical. During the production, the producer’s already warned me years ahead of completion that there are too many films on the market. In France alone there are 15 or 20 new films a week, and that includes some re-releases of big classics, but mostly new films. That’s far too much. The audience gets overwhelmed with choice. However well it’s made, if a film comes out, it may disappear immediately, simply because there’s a wave of new films surrounding all the time. Basically it’s a very very competitive market, more than ever, and a film needs to be noticed as soon as it is born, and not just because it’s a beautiful film because that’s not enough. It needs to be noticed whatever way. I am an unknown filmmaker, or in the animation world I’m a little bit known, but basically the audience out there doesn’t know my name. They know Studio Ghibli—that’s great, it helps a lot, but they don’t know me, and it’s my first film. [The producers] said “so let’s get the film finished in time to send it to Cannes Film Festival. If Cannes selects the film, then we are really lucky that we are in, that is great”, and that’s exactly what happened. The fact that it won Un Certain Regard special prize is even better, but in a way the fact that it was selected—and that it got full attention of the press in Cannes itself—was already what we really needed and what we really wanted.

That’s all I wanted to ask. Thank you so much again for the film. I understand it’s premiering at the London Film Festival next month and you’re based in London—that must be a big occasion, so all the best for that as well.

Yes, you’ve done your research! It is a big moment. For me, a big moment was when it was premiered in Tokyo about ten days ago, I was there too. I’ve got a strong relationship with Tokyo, and the fact that I was there and literally could say to the audience “here is my film, I hope you enjoy it”, that was a big moment, I have to say. Another big moment for me: I’m from Holland originally, I grew up in Holland, and to go to Amsterdam and show it to a big audience there was really nice too.

OK, well I hope you have many more big moments like that. Thank you again Michaël, and all the best.

Thank you, Dominic.

The Red Turtle receives a limited release on September 22, courtesy of Transmission. For screening locations, visit their website.