She is looking out from my computer screen in my small bedroom. I rarely feel I have license to look at another’s face like that – a stranger on a train, a friend over for dinner, even a lover in bed might reproach, why are you looking at me?

Here, in her film, I look at her, nothing else to do. She’s only a stranger to me, Chantal Akerman. It’s her 1974 film Je tu il elle, where she cast herself as one of the three characters appearing in three elegant chapters. She is young, shapely; she inhabits a near empty apartment, relocates herself from corner to corner like a lunatic, moves the mattress, takes off her clothes, puts them back on, eats spoonfuls of sugar, arranges sheets of paper covered with writing on the ground, days pass. She lies, listens to her own breath, attuned to delicacy of being. Later, this beastly figure looks out the window and you hear a soft and surprised voice: “When I looked up, suddenly, there were people walking on the street.” Comedy of the poor, fragile brain, locked in a room. There are other people! And then she presents herself in a close-up, with these pressed lips and a cunning look in her eyes, smiling. Peculiar pain shadows her comedy like a gust of wind without a source in a room. She stands, a bare-bones image, plain like a white sheet; I think, why is this so moving, so sad? Wait, am I close to crying? It’s just an image!

*

At last year’s Locarno Film Festival Akerman premiered her final film, No Home Movie. In an interview, critic Daniel Kasman questioned her about the difficulties of presenting a film that is so painfully intimate – the film consists of filmed moments Chantal shared with her dying mother, Nelly Akerman. “And my poor mother, who is not even there to enjoy it. Oof! I found it so terrifying and ironic.” Kasman is uneasy: “Ironic?” “Ironic because that big crowd who is there, who can destroy you,” Akerman replies. “And my poor mother who died and is not there any more.”

When Roland Barthes wrote his final book, the now classic text on photography Camera Lucida, he too was haunted by death. Flat death, he called it, writing on the horrific ‘platitude’ of death: “Nothing to say about the death of one whom I love most, nothing to say about her photograph, which I contemplate without ever being able to get to the heart of it, to transform it. The only ‘thought’ I can have is that at the end of this first death, my own is inscribed; between the two, nothing more than waiting; I have no other resource than this irony: to speak of the ‘nothing to say.’1 Barthes, staring death in the face, is shaken by a blunt and most moving image: a photograph of his mother.

In her Paris apartment, on October 5th 2015, months after Nelly died, Chantal Akerman took her own life. Words signifying this flat fact, along with other facts of her life, were scattered across the internet in repetitive eulogies: she was 65, a film director, a master of 20th-century avant-garde cinema, a Belgian Jew, a nomad, her parents Polish migrants, her mother an Auschwitz survivor.

Months later, I’d still catch myself thinking, she is gone.

Yet there she is, staring out into space in my small room: Chantal Akerman. I know it’s melodramatic, to imagine her as a real being, really in my room. But that’s cinema, it’s strange like that. Akerman left an image in time, a mystery you cannot speak, cannot unlock and cannot break.

Is it just an image?

Sometimes a work of art delivers a feeling of another’s hand reaching into you, a lover’s gripping hand. I guess intimacy has something to do with possibility of love. With film, this longing is strange, tangled. There’s film’s mechanical, collective production, distancing me from the maker and from the film’s subjects. Looking at an image on a screen, what is it that I see? The thing in front of me is not Chantal – it is a ghost, a copy, a picture on a screen. Barthes, for one, was amazed at what he was actually looking at in a photograph. Mythically glued, the photograph and the thing in it are like “pairs of fish which navigate in a convoy (sharks, I think, according to Michelet), as though united by eternal coitus.” How else to explain the spooky relation but with dubious science? And what about in cinema? Nothing is simple, Akerman was fond of saying. Walter Benjamin, in his famous essay The Age of Art in Mechanical Reproduction, thinks a work of art loses a certain aura once reproduced. Benjamin’s aura is somewhat like Barthes’ travelling sharks, something special, ‘glued’ to an original object of art. There’s no original when it comes to film, inherently a film is a reproduction. Barthes, with his romantic imagination, finds aura in photographs. He calls it noeme, ‘that-has-been,’ the quality that photographs have of cementing a moment in time, that something actually happened. He stubbornly refuses this noeme in film – it’s simply not private like a photograph, the image moves, the actors are performing, what even is film!

Aura, privacy, authenticity. Is intimacy in art not predicated on these dreams of ownership? A feeling I secretly harbour that a particular work of art speaks to me in a special way, is waiting to be seen by me, and is in fact conceived for my heart alone, as though it is Mum making up a special bedtime story to get me to sleep? How can cinema, the medium of the masses, with its brutal collective robotics, deliver this delicate illusion?

*

Chantal Akerman decided to make films at age 15 when, inspired by Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou, she realised that cinema could be poetry. After making a short film, Blow Up My Town, she briefly went to Israel, and in 1971 moved to New York. Amongst New York’s burgeoning streets, its dirty squares and mad buildings, film was bursting. For a group of structural filmmakers of the ’70s, narrative was a crusty old winter hat stuffed in the corner on the top drawer – it was time that was exciting, it was space. At age 21, Akerman short-changed customers at a gay porn theatre, amongst other odd jobs, saving cash so that she could make films.

She watched films. In New York’s East Village, Jonas Mekas had established the Anthology Film Archives, an independent cinema and library where the structural experiments were stored, distributed and screened. Here, she allegedly spent a total of 12 hours watching Michael Snow’s three-hour La Région centrale on repeat, alongside her new friend and future collaborator Babette Mangolte. Babette remembers them agreeing that it was “the most beautiful film they’ve ever seen.”2 Snow, a Canadian experimentalist, aimed to abscise the maker’s hand – he left it to a pre-programmed robotic arm to relentlessly record a Canadian mountain landscape, reaching toward a mechanic totality. What Akerman discovered was the “relationship between film and your body, time as the most important thing in film, time and energy.”3 She saw Mekas’ beautiful diary films, too: he caught the literal everyday, the crumbs of life, and crafted the found images into rhythmic visual poetry.

Babette Mangolte worked with and introduced Akerman to Yvonne Rainer, a dancer and a feminist filmmaker with a strange recalcitrant body that she willed into becoming a revolutionary tool. Rainer, who also concerned herself with the tiniest movements that make up a day, once made her dancers move mattresses around a room because she found it hilarious (did Akerman borrow her obscene mattress in Je tu il elle from Rainer?). And then there were the films of Andy Warhol: delirious, irreverent experiments where people simply sat, and breathed, and talked shit.

In New York, Akerman discovered the vertical and horizontal mysteries of cinema’s space-time. Her lifelong experimentation with space and duration left an indelible mark on cinema. The wide, precisely constructed shot held for a long time, in which often, nothing happens, can today feel to film festival attendees like the bane of serious art cinema. It’s easy to forget that this way of being inside a cinematic space was conceived as an act of magnificent resistance – against convention, against the relentless speed of capitalism, against one’s own ignorance and impatience, against expectation.

In 1972, Chantal lay in a bed and Babette Mangolte, the cinematographer, rotated their camera through space, filming; they titled this short work La Chambre. There, Chantal appeared, holding an apple; there again, blinking. The gorgeous room was sort of melting in light, so the lines making up the luscious images flattened; the young woman lay the bed, losing her own body in visual abstraction. Time grew. Chantal lay in bed. Lay? For there she is, now, again, she holds the apple, she blinks. Where am I? In my room, in my bed? Or in the New York room, 1972? Arresting her room in time, Chantal showed us how cinema messes with one’s personal delicate balance of time and space.

“We live fixations, fixations of happiness,” Gaston Bachelard mused on the topic of memories and places in his adored treatise The Poetics of Space.4 But a viewer of Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles—the film that earned Akerman her place in cinema’s history—would not think such happy thoughts about houses. We are given co-ordinates, tethering a woman to her place. At 23 quai du Commerce, Jeanne Dielman lives, an ageless mannequin mother played by strikingly white, precise Delphine Seyrig, and her tragedy is a collapse under objects. Pressing buttons, flicking switches, adjusting saucers on plates and napkins in rings, lifting unruly lids, boiling potatoes – that’s her lonely rhythm. There’s psychology and there’s politics: disconnect with her annoying son, her labour of housework and prostituting. But more horrible is the human body existing in the house. The house is prison. Was it this confronting discomfort of a normal living space that made so many (including, notably, Marguerite Duras) hate this three-hour film at its Cannes premiere?

Jeanne Dielman is a metaphysical thriller, where malevolent props of domesticity stifle an individual slowly and mercilessly, and Akerman’s sustained continuity of the banal leads to an insane explosion. Much like in Blow Up My Town, that first short film in which Akerman literally blows herself up, unable to bear a grotesque kitchen, Jeanne Dielman’s explosion is an explosion of self.

Why did the 25 year-old director see such a profound anxiety shaking the walls of the house? In these early films, and recurring all throughout her work, the room is a horrifically inverted ‘room of one’s own.’ It’s history: “I was obsessed by the way when she went out of the camps she made her house into a jail. That’s Jeanne Dielman,” she told Kasman. Nelly Akerman didn’t speak about the camps (horror and its platitude?), but in her childhood Chantal woke up from nightmares, long before her aunt told her Nelly was interned at Auschwitz.

And so, Akerman studied the room/prison passionately, she knew the many ways one can become prisoner. Rooms are everywhere in her films. “The passions simmer and resimmer in solitude: the passionate being prepares his explosions and his exploits in this solitude,” Bachelard writes. In her rooms you find both solitude and passion, you find people – people in thought, people sitting, people eating, smoking, people speaking and not speaking, people moving, people struck down by emotion, loving and not loving, breaking, breaking each other. Not only fears, but feelings too, can be the stuff lining a prison’s walls. Feet, arms knocking in tenderness and gluttony, two women consume each other in a stark bed, ending Je tu il elle in brief respite from the loneliness of existence. Chantal leaves and Claire sleeps, alone in her bed, and when the film ends she’ll wake to find the loving visitor gone. Bed – another treacherous stage, for in bed there’s not only love-making, like some films will have us believe. Bed is also where we wake up in the middle of the night, helplessly stranded, to discover a uniquely dark small world.

When you google Chantal Akerman, a photograph comes up, the director lies in bed with a cigarette. Is that really her press shot? Sometimes, she directed her films in pyjamas. And even the sweetest of her beds must be escaped – in Nuit et jour the protagonist exists the house in the final shot, throws her heels into a bin, and walks down the street, to liberate herself from possessive male lovers, from repetition and boredom, from her own prison.

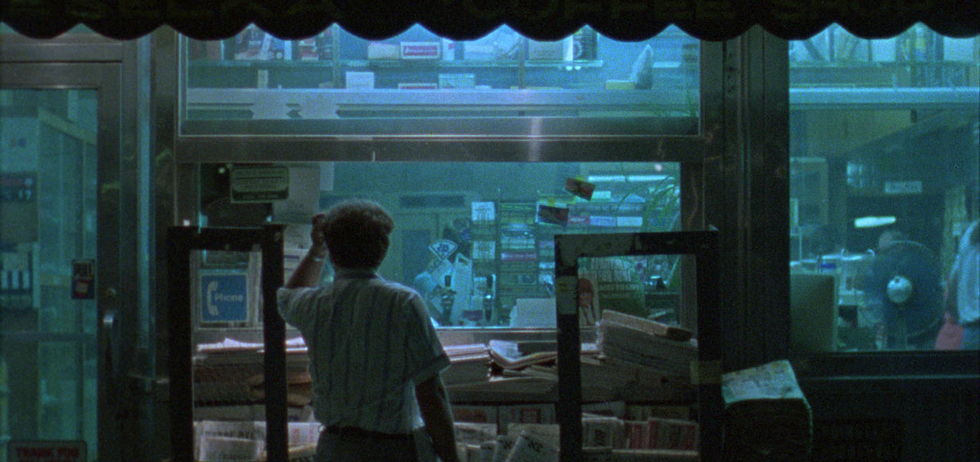

We enter Akerman’s rooms, and wait – we get to know time, the fourth dimension that rules the moving image. Jeanne Dielman peels potatoes. A girl eats a sandwich. The film director lies in bed. What happens when I’m stuck waiting? “Poor people wait a lot. Welfare, unemployment lines, laundromats, phone booths, emergency rooms, jails, etc.,” writes the wry Lucia Berlin in her short story The Manual for Cleaning Women. The waiting of the poor is made visible in Akerman’s documentaries, News from Home and D’Est: the camera floats outside, in New York and through post-Soviet Eastern Bloc respectively, floats onto streets and into train stations and finds people waiting, asks us to wait with them. Lovers, like poor people, also wait: the phone that will never ring, a word that will never be said, an hour turning into agonising eternity (Je tu el elle, Les Rendz-vous d’Anna, Toute Une Nuit, Nuit en jour, Portrait of a Young Girl in the Late ’60s in Brussels).

There’s another kind of waiting, hidden in cinema’s images. It obsessed Barthes when he looked at photographs, and I think of it watching her films: to realise that the faces we look at no longer live (Akerman herself no longer lives). The human face, reproduced as image, an autumn leaf that breaks off its branch and is doomed to roam in the wind for eternity, even when the body it was somehow attached to no longer exists. “What are you waiting for? There’s nothing to wait for in this world,” a woman tells a waiting man on the street in Akerman’s Histoires d’Amerique: Food, Family and Philosophy. Isn’t the ultimate waiting, the waiting that cancels out all the waiting we do in our days, that capitalism with its life affirming positivity would love to deny, our waiting for death? Poverty, love, art, death – are they the opposites of progress? Yet Akerman isn’t lost in metaphor:

“Yesterday, today and tomorrow, there were, there will be, there are at this very moment people whom history (which no longer even has a capital H), whom history has struck down. People who are waiting there, packed together, to be killed, beaten or starved or who walk without knowing where they are going, in groups or alone.”5

History is what haunts her.

*

Cinema may be “death at work”, according to Jean Cocteau, but it also testifies that we once were. Akerman made a private world visible, a woman’s private world. She was interested solely in the quotidian. Reality is irreducible. Things happen, only once – each thing, each small gesture, each life deserves a poet’s gaze. She didn’t buy the old cliché that fiction must tell remarkable stories, a documentarian film remarkable subjects. Being is enough. I think it is a remarkable feat of compassion to construct a film out of a woman’s routine in her kitchen. “We must believe in the reality of time. Otherwise we are in a dream,” said the the French philosopher Simone Weil, who longed for proof that the world exists.6 Doesn’t cinema give us that promise?

An art object’s mystical aura, glued to the original, hasn’t withered in film – I disagree with Benjamin. Aura is in the moment, or rather it is the moment. That’s Akerman’s argument. Cinema is uniquely real, and therefore uniquely intimate, actual people, actually living. And perhaps, had Barthes known and understood Akerman’s work, he would’ve considered that cinema, too, can assert the intimate actuality of life, his noeme, as powerfully as photographs. Her legacy is proof that cinema can be lived experience.

I really love her very simple, unadorned documentary One Day Pina Asked… , about another kindred spirit with a passion for the everyday, choreographer Pina Bausch (who had great influence on Akerman’s work from the ’80s onwards). “My film is about her unwavering quest for love,” Akerman says as the film opens. Akerman’s films face death, but they also resist it, in the simple fact of their own existence. In her tender attention to people, as they are, Akerman herself was on that quest.

And what about intimacy? Of course, nothing is simple. After all, why do I long, why should I long, for intimacy in cinema? Why should I, like a baby, wait for Mum’s bedtime story; why should I greedily imagine that Akerman’s images touch me like a lover touches me; I am dreaming, am I blind?

Walter Benjamin was not sad about the withering of aura; he hoped that mechanical reproduction would offer radical political renewal. What’s important is not the old aura, but the fact that images rise anew in the act of watching: “In permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced.”7 His ideas call for a political relation to images, “a tremendous shattering of tradition.” Reactivation is exciting, it breathes life into the technological age and empowers the beholder’s interpretation.

*

Germaine Greer is suspicious of women artists’ repeated use of their own bodies in their work: “The woman who displays her own body as her artwork seems to me to be travelling in the tracks of an outworn tradition that spirals downward and inward to nothingness.” It is a short and flawed opinion piece, yet don’t we feel a subconscious unease that Greer has a point? Is the feeling of intimacy in art entwined with narcissism, somewhat opposed to Benjamin’s shattering political hopes? And is it stereotypically, abjectly female?

Akerman is spoken of as a cinematic narcissist, as well as one of the most intimate film artists. It’s the repetitions, the claustrophobia, the relentless circling, it’s her mother, her self. Even when we are not locked in one of her rooms, she seeks out distinctly personal images, like the waiting queues in D’Est. We listen to her reading from her mother’s letters even as the camera coolly traverses New York streets in News from Home. She always placed her camera at her own height with narrow subjectivity, exercised obsessive control of the frames. In an insightful and sensitive essay for LOLA journal, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum can’t avoid it: “Most of her films, regardless of genre, come across as melancholy, narcissistic meditations charged with feelings of loneliness and anxiety.” So intimate was the experience of watching No Home Movie at Locarno, Daniel Kasman reported it “felt almost indiscreet.”

Even in the privacy of my own room, streaming No Home Movie feels indiscreet. This is her most personal film, the most real; intimate to the point of discomfort. Like Barthes, obsessively returning to the photograph of his mother (the photograph that truly moves him), Akerman returns to her own mother’s home, the actual quotidian: curtains swaying, fridge opening, closing, Evian water bottles, drying sheets, an iron on the window sill. What suddenly strikes me is that the little Nelly Akerman’s nails are finely painted red, even though she hardly has energy to stay awake during the day. I think of the impeccable Jeanne Dielman, not as a fictional character in Chantal’s film but a real woman, confronted by the real passage of time. There’s a rueful introspection to the film, it’s hard to pin down. Cinema, cinema, cinema, Akerman seems to be questioning. What does it matter, in the face of real life? In this final film, she can’t ward off the platitude of death, all over her mother’s apartment, creeping behind doors.

In the Locarno interview, Akerman frankly recalled that after a premiere of her film Almayer’s Folly, her mother told her, “You have all that, and I had only Auschwitz.” I found the next confession chilling: “And then I realized that same moment that I could not speak on her behalf, she was the only one who could speak, and if she didn’t want to speak, that should be it.”

Akerman wanted to speak. She unashamedly made work about her own life, used her own body. Insistence on self was her resistance. She resisted everything: traditions, stereotypes, categories. She resisted being seen as a feminist or LGBT filmmaker, objected to Je tu il elle being screened at a gay and lesbian film festival in New York (even if she became increasingly important to both feminist and LGBT movements). Here she is, telling Nicole Brenez that she loved Robert Bresson’s classic film Diary of a Country Priest, for the priest’s ear: “In my whole life I’ve never seen such a great ear, I stared at it endlessly. This is why ‘Catholic filmmaker’ [Bresson was a Catholic], ‘Jewish filmmaker’, ‘woman filmmaker’, ‘gay filmmaker’ – all these labels have to be thrown away, that’s not where things really happen.” She wanted to rise above women are ‘this’ and men are ‘that’. Women are, men are, and what the camera does is frame them. It’s what one chooses to frame. Her narcissism emerged from the force of this conviction. She desperately wanted to be, simply, Akerman.

She was. ‘Jewish filmmaker,’ ‘woman filmmaker,’ ‘gay filmmaker’ – that’s our interpretation, each viewer’s irrevocable reactivation fraught with our personal and collective politics. No work of art is universal; ‘universal’ art is a farce. She just stands, staring out from my computer screen. Akerman lived Godard’s ‘cinema is truth at 24 frames per second’ motto. Aura is the moment, she breathes. Reactivation of an art object is possible because something was arrested in time and space. Images, whatever you and I make of them, assert the possibility of life and with it, possibility of love.

If cementing ‘personal as political’ is one of feminism’s great achievements of the last century, Akerman’s work does exist in the feminist project. And while 20th-century feminism clarified the slogan in mass media, the idea was first defended by the poet Sappho, who in 7th Century BC swept Homer’s epic concerns away with:

“Some men say cavalry, some men say infantry,

some men say the navy’s the loveliest thing

on this black earth, but I say it’s what-

ever you love”8

*

I sit in my room. Nothing much is happening, I’m simply breathing. I look up, the ceiling is up there, around me are walls. Passions simmer and resimmer in solitude. Nothing much is happening, except—I am alive. I look at the screen, I look out the window, I know – there are other people. I think about women’s unwavering quests for love. Perhaps it’s melodramatic, to imagine intimacy of images. Intimacy, love, isn’t it what we long for in art, in life?

Alena Lodkina is a Russian-born experimental filmmaker based in Melbourne. Her short film There Is No Such Thing as a Jellyfish premiered at the 2014 Melbourne International Film Festival and her latest short film Lightning Ridge: The Land of Black Opals will have its Australian premiere at the Antenna Documentary Film Festival in October.