The Grab Bag is an annual piece here at 4:3, where we write on things that falls outside the ambit of any ‘best films’ list. The guidelines for submission were intentionally vague so what follows is an amusing and eclectic group of highlights, from scene transitions to Indian film music, and the state of the horror genre itself.

Virat Nehru: Indian cinema often gets a bad rap for using music in its own methodological way. The majority of film-based music that gets released does not necessarily feature a film’s score. The main attraction in terms of Indian film music still remains the kind of choreographed song and dance numbers most global audiences associate with commercial, mainstream Bollywood. Hence, I thought I’d take this opportunity to highlight a couple of interesting experiments that happened in Indian film music this past year.

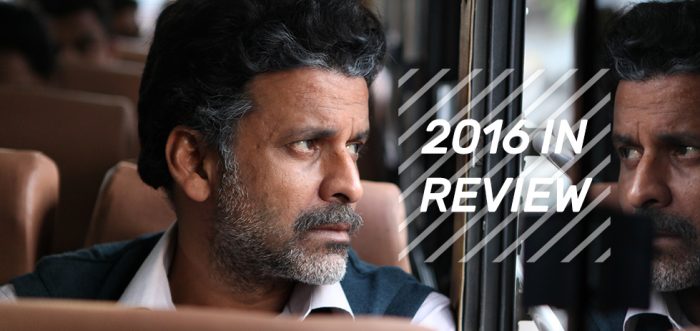

First, let’s turn to Hansal Mehta’s Aligarh (pictured above). It’s perhaps the most nuanced film made to date about the Indian male queer experience. This is a landmark in itself because of two reasons – the Indian legal system recently recriminalised homsexuality, and also, representations of queer characters in mainstream Indian cinema have often been reduced to caricatures and negative stereotypes. The film’s highlight is this three-and-a-half minute sequence that occurs somewhere in the middle. In this scene, the film’s protagonist – struggling to come to terms with his own sexual identity and the social stigma that comes with it – is locked away alone in his room. An old song starts playing on the radio – “Aap Ki Nazron Ne Samjha”, a song about submission to your beloved and submission to the circumstances you find yourself in. Manoj Bajpayee, who plays the aggrieved protagonist, acts out the entire emotional arc of the narrative within these few moments. The impact is almost Shakespearean – the ebb and flow of the song on the radio mirroring the inner emotional turmoil of the protagonist. And yet, despite the dramatic nature of the scene, the execution is refreshingly understated. Bajpayee is my pick for the best acting performance this year based on this sequence alone.

There is perhaps no better example of the diversity of Indian cinema this year – and subsequently, the need to widen the default focus from Bollywood – than Nagraj Manjule’s Sairat. It was shown at the Berlinale this year and has now found it’s way onto Netflix. It became the first ever Indian film to record its music score at Sony Scoring Stage (previously MGM studios) in Hollywood. The film has four music tracks, all of them backed by a symphonic orchestra comprising of sixty six musicians – including a forty five member string section, six-piece woodwinds, a thirteen member brass section and a harpist – all led by conductor Mark Graham. The soundtrack brings together elements of Indian Maharashtrian folk music, Celtic tunes and Western classical music, providing a fresh and innovative dynamic to fusion sensibilities between Indian and Western musical influences. The compositions themselves are rebellious experiments, going against the established trends in Indian music today. However, western audiences would find much to like in the soundtrack – as it is a lot closer to the sensibilities of what a ‘film score’ has come to mean globally – than the expansively choreographed song and dance numbers that remain peculiar to mainstream Indian cinema.

Conor Bateman: Adam Curtis’ latest, the 166-minute HyperNormalisation, was released through the BBC iPlayer in October. I found it to be a fairly disappointing online venture for Curtis; where last year’s Bitter Lake was a relatively pared back affair that felt like a self-contained film, HyperNormalisation is a sprawling mess that feels like a series of short episodes clumsily strung together to form an ultimately unconvincing patchwork analysis of global trends. What’s striking, though, is that short sections within the film, taken on their own, are quite extraordinary. Chief among them might be Curtis’ compelling counter-history of the West’s involvement with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, which renders the Bush-Blair “War on Terror” little more than Wag the Dog. Another impressive sequence, one which harked back to the near-perfect merger of sound and image in Curtis’ It Felt Like a Kiss, is the “Dream Baby Dream” montage. Curtis pairs the Suicide track with clips from pre-9/11 Hollywood disaster films, zeroing in on the casual barbarity of big-budget spectacle and the collective fantasy of self-destruction. Yes, it’s not a particularly original sequence, considering that a feature-length version of this premise exists in The Anti-Banality Union’s Unclear Holocaust, but it is certainly effective.

The best piece of editing I’ve seen this year, though, isn’t in Curtis’ film. Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson jumps between places and decades, collating clips from documentary films and their making on which Johnson was cinematographer. This anchors the entire film within Johnson’s point of view, making it a singular work of film-as-memoir. The film’s editor, Nels Bangerter, is able to stitch together disparate focuses in a way that has a powerful, unexpected resonance. The editing moment that has stuck with me for months involves linking footage from an understaffed and resource-poor hospital in Nigeria, as a newborn baby struggles to breathe, and footage from a boxing match in Brooklyn. The losing boxer storms out of the ring and into the locker room, shouting and smacking the wall. Johnson follows him the whole way. He moves into the shower room as Johnson stops. We hear him shouting again. Then: he emerges, rushing past the camera, down the hall, into the crowd, through the aisles until he finds his mother, who embraces him and tells him “You did a great job, baby.”

Two short segments I want to also point out here that I omitted in my end of year list, solely because of their unusual modes of release. Andrew Infante’s omnibus film I Want a Best Friend premiered on Kinet, a free online publishing platform for low-budget avant-garde and experimental cinema. Alexa Harrington’s segment in the film really stood out to me, a fascinating and powerful short in the desktop documentary mould. From another online publisher, Now! Journal, I want to single out Dan Albright’s Baton Rouge to Jackson ‘63, which displays found footage side-by-side in two channels. As the title suggests, the video we see is from Baton Rouge in 2016 and Jackson, Mississippi in 1963, but the film is potent in just how similar the images are. Riot police attack young people on private property, but where the 1963 footage is from the perspective of a journalist standing amidst the police, the 2016 footage is from a mobile phone, one of the young protesters capturing the needless violence that ensues. Making things even more startling: in 1963 the police are armed with batons, in 2016 they have large guns, fingers ever-poised on their triggers.

Jeremy Elphick: One of the most recent memories from film in 2016 is a single, sustained shot from Midi Z’ The Road to Mandalay. Inside a textile factory, a camera lingers as light refracts and bounces off strands of white silk gently being tugged by one of the film’s protagonists Lianqing, the other, Guo, watching from the other side. Midi Z paints a contrast in this single shot that frames the rest of his film, as well as offering one of the most beautiful images in cinema of the year. The shot echoes how these characters are revealed and covered up, over and over again, as their cycle of labour continues throughout the film. I remember hearing an audible gasp of awe which was something I’ve rarely, if ever, heard in response to such an otherwise muted scene.

Eduardo Williams has been making short films – my personal favourites: Could See A Puma, The Sound of Stars Dazes Me, I Forgot! – that have constantly pushed their formal constraints, and offered something genuinely thought-provoking in the way they make aesthetic choices within the medium. Considering that he’s been doing it since 2006, there was a certain anticipation to his feature-length debut, The Human Surge – which has gone on to become one of my favourite films of 2016. Watching Williams’ transpose his stylistic and technical ideas about cinema into a full-length setting is made more fascinating by the structure he’s chosen, and more so, the way in which he moves within it. Each of the 3 sections of the film sustain themselves as their own peculiar stories, however, Williams’ approach to the transitions between these narratives offers one of the most original and fascinating approaches to film this year. A camera fixated on a group of young men doing a live cam show in Buenos Aries suddenly jumps through the screen; as the narrative then shifts onto a group watching a show in Mozambique. Later, one of them takes a piss, with the camera panning to face to dirt, before going far beyond: zooming in on an ant, then deeper… eventually emerging at the location of the last narrative arc Philippines. It’s easy to see what Williams meant when he told Mubi’s Notebook that “nature is a kind of technology” – it’s a statement that encompasses a huge chunk of how his films bounce these two massive spheres against one another. With The Human Surge, he’s articulated this concept better than ever, and it’s difficult to imagine how he would’ve achieved this without the unique coherency afforded by his sharply unique approach to space; which is epitomised in these shifts between stories arguably better than anywhere else in the film.

While this last point doesn’t exactly fall into my favourite elements from a film, I thought the nature of the way we do the Grab-Bag would give some malleability. There were a few independent film journals, that offered really interesting modes of engagement with specific focuses on cinema this year. Fireflies #4, focusing on Pedro Costa and Ben Rivers, is the latest in a series of huge improvements on previous issues – putting it next to issue #1 of the journal really shows how far this publication has come. My favourite new publication to arrive this year is NANG – with the 1st issue of 10 focusing specifically on screenwriting, within the magazine’s broader focus on Asian Cinema. The presentation is beautiful, with a precise attention to detail throughout, and a clear skill when it comes to building the grounds for later issues to come. In terms of broader approaches to film criticism, Fanta Sylla’s initiative of The Black Film Critic’s Syllabus is one of the most impressive film resources to emerge in 2016, with the cooperative use of ‘google docs’ to make it indicative of how databases, reference, and knowledge around areas of film and criticism neglected by mainstream discourse.

Dominic Barlow: INT. CINEMA – NIGHT. Swiss Army Man is screening, i.e. the “farting corpse” movie starring Paul Dano as a desert survivor with a beard and Dan Radcliffe as an actor with an apparent career death wish a cadaver with several applications for Hank’s survival. You are there, for whatever reason: festival hype, bored hatewatch after scoffing at the plot synopsis, residual Little Miss Sunshine/Potter nostalgia. It’s directed by “Daniels”, a cute mononym that screams of a PR agency but actually refers to music video directors Daniel Scheinert and Daniel Kwan, who are as competent as that industry tends to make them – handsome framing, distinctive title cards, decent sound design. More than that, they’re quietly aware of themselves. The score (newcomers Andy Hull and Robert McDowell) is every badly-hummed “can you do this kinda thing” directive thrown by an amateur director at their composer, with placeholder lyrics ripped from one of those Literal Music Video gags (“now we killed a raccoon / we are using your body like it’s a machine gun”). It’s woeful in theory, but next to competent editing (Matthew Hannam of Enemy and Antibirth) that straddles quiet dialogues and whiplash-heavy action sequences, it’s gratifyingly impossible to take seriously.

Still, your jaded self says that will go south somewhere around the 40-minute mark, where the college-screenwriter drama and romance will be dropped. And yet, that’s not how it goes. Scheinert and Kwan are wise to the way hapless men’s importance is overinflated by non-studio filmmakers – they would have to be to get Mary E. Winstead, Faults producer, in the cast – and better still, they are willing to look hard at where their gross patchworks of the opposite sex come from. Hank’s journey down from the clouds is their own: unlike so many starry-eyed film students before them, they aren’t lost in the montages conjured by their egos. Instead, they rip them off like band-aids congealed over their whole young adulthood. A late twist only proves their self-scrutiny. The ending, baffling and hilarious, proves their artistry. The sum total, stronger in such gestures than in emotional heft, doesn’t dwell in your mind for too long after you’ve left the theatre. At the year’s end, though, it’s an odd moment amid “respectable” remembrance – a fart from the rolling tide – that’s worth holding onto.

JD Caruso: Films which broadly sit within the horror genre have had a particularly interesting year in Australia, perhaps most notably in their treatment by distributors. Kicked off by the theatrical success of Rialto’s It Follows last year, a fair few choice indie-horror films that would have previously been relegated to a few festival screenings or immediate home video release – ranging from Rialto’s fantastic Green Room and Monster Pictures’ I Am Not a Serial Killer, to Universal’s overhyped The Witch, to Roadshow’s downright unwatchable Kevin Smith trash-fest Yoga Hosers1 – have seen a domestic theatrical run. While these films’ financial takes don’t hold a candle to It Follows’ success,2 this trend looks to be continuing into the new year, with a theatrical run of Julia Ducournau’s well-crafted cannibal-focused debut Raw in the works, off the back of its premiere at this year’s Kier-La Janisse-helmed Monster Fest.3 Additionally, the entry of players like JBG Pictures and Cinema Asia into the market has seen an influx of theatrical releases for niche Asian horror, with The Wailing4 and Train to Busan seeing success in limited release in spite of the lack of any substantive English-language marketing materials from JBG.

While Blumhouse releases seem to be going from strength to strength internationally, in Australia the picture is a bit more murky, with only one film on their release slate (Mike Flanagan’s franchise-redeeming Ouija: Origin of Evil) making it to the big screen compared to last year’s six wide releases.5 The Purge: Election Year was a notable absence, although it’s worth noting that no Purge film has seen theatrical release in Australia, despite their international and home video success. Blumhouse looks to have been experimenting with their traditional release model this year; about half of their release slate (including another Mike Flanagan-directed film, Hush) went straight to VOD platforms, with only a few garnering an additional limited theatrical release. Next year sees the release of M. Night Shyamalan’s Split, James Gunn’s The Belko Experiment and new entries into the Insidious and Amityville franchises, signalling a return to their traditional release strategy.

Don’t Breathe surprised both critically and financially, taking just shy of $148 million internationally and $5 million domestically on a $9.9 million budget, while Adam Wingard’s Blair Witch sequel/remake hybrid underwhelmed both critically and financially (despite, I’d argue, being a fairly strong film in its own right), Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon got a cursory run in indie houses (pretty much compulsory, given its director), The Shallows brought shark-terror back to the screen and reignited the flame of Twitter’s most incessant vulgar auteurists (sorry, the film isn’t very good), Lights Out marked another instance of non-Blumhouse operators aping the Blumhouse model to moderate financial success,6 10 Cloverfield Lane conned audiences into thinking it was a good movie, Underworld: Blood Wars demonstrated the franchise could become even more convoluted, The Conjuring 2 reminded us that filmmakers have an inability to discuss working-class Britain without slipping London Calling somewhere onto the soundtrack,7 and the oft forgotten Pride and Prejudice and Zombies echoed its woeful US run, bringing in a limited release-level box office in wide release, despite not being a particularly bad movie (all things considered).

As always, some of the best horror content was relegated to the festival circuit and home video, with Safe Neighborhood, We Are The Flesh, Killing Ground, Always Shine, The Devil’s Candy, Trash Fire, Baskin and Under the Shadow failing to garner even a limited release, upsetting as Safe Neighbourhood, Killing Ground and The Devil’s Candy have Australian directors. I guess it’s important to make room for Spin Out and its weak equivalents, although with a life on the international festival circuit on the horizon for some, including Killing Ground, there’s still hope. Internationally, boutique labels demonstrated themselves to be far more equipped to deal with studio content than the studios themselves, with Shout! Factory releasing a definitive (and director-approved) fan-edit of Raising Cain and bringing Australian Geoffrey Wright’s absolutely bizarre teen-orgy laden Cherry Falls back into public consciousness, Bad Robot’s remaster of Phantasm finding a home on Well Go USA,8 and Arrow Video continuing to out-Criterion the Criterion Collection, albeit with a trash-cinema focus (this year’s release of Ozsploitation flick Dead End Drive-In is a notable example).

VOD platforms like Vimeo have proved once again that there can be a home for independent oddities which fulfil a highly specific niche to find their audience – Scott Schirmer/Bandit Motion Pictures’ enviro-fungal love-host softcore-lite experiment Harvest Lake and last year’s Night of Horror Best Film winner Be My Cat: A Film for Anne, a post-found-footage Anne Hathaway stalker-flick from Romania, are notable examples. While Australia hasn’t quite caught up to the standard of international labels and streaming services in terms of boutique content – Glass Doll Films and Monster Pictures are starting to get there – horror is definitely alive and kicking in Australia and its fan base and mainstream appeal looks to be, on the whole, broadening rather than contracting.

Keva York: In an alternative version of present day London, humans have embraced their bestial origins, exchanging language for grunts and shrieks and the customs of surburban life for the law of the jungle. Such is the premise of Steve Oram’s directorial debut Aaaaaaaah!, an unholy cross between a sitcom and a nature documentary. That Oram took an idea that sounds like it should be a two-minute sketch and spun it out into a truly bizarre and disarming feature-length film is noteworthy in itself. However, I’d like to single out Julian Barratt’s performance as Jupiter, the usurped alpha male of the family, as a particular highlight.

Shunted from the house, Jupiter is camped out in the backyard, nursing his physical and emotional wounds. He approaches his former home, gazing through the kitchen window, and his daughter passes him out a battenberg cake; a token of sympathy. Jupiter does not eat the cake but curls up with it, gazing with deep sadness and tenderness at the little frosted loaf. Barratt is very good at manifesting such weirdly poignant moments in a film mostly propelled by varying levels of gross-out ludic madness (though he can do that too). Certainly Aaaaaaaah! is not a film for everyone but aficionados of perverse and brutal British comedy à la Jam and Brass Eye will most likely appreciate this savage satire.

Kate Prendergast: After a prank call sends a plane crashing into an orphanage, the Delta Bi frat boys are suspended to a sorority house in Old Parchtown, whose inhabitants they also managed to accidentally turn to gristle. Brent (along with bullied cross-dressing Asian vegetarian, Sizzler) is the new pledge – but what he’s really in for is to avenge his identical twin Brock, who had his throat ripped open by serial dude bro killer Motherface. Hyperviolent, heads-exploding, guts-down-the-loo shlock horror, Dude Bro Party Massacre III9 has got to be the hammiest of surreal send-ups on white male college humour and white male American ‘innocence’ out there. It’s crude (see: man humping child’s gravestone), misogynist (see: Samantha and her plate of cookies), offensive (see: talking ghost embryo) and so so dumb (see: previous brackets, and the film). The self-reflexivity punches you in the kidneys. It’s great.

I could pick out so many elements of this 5-Second Film kickstarter to be wrapped in the sacred threads of Grab-Bag. There are the endlessly creative methods of gore (“Look, ZQ’s overcome his fear of heights!” the dudes beam in the river below, before a torso sails overhead on flying fox). There are the time-warping flashbacks, the no-budget props and sets, the uncalled-for animation, the weird Italian spectre that hijacks the subtitles to tell his wife he loves her, and the Darkplace-worthy editing, which made the hostile attic dance sequence between a replicant and Brent the most tensely joyous thing I have seen all year. And whichever of the nine writers (the same nine that make up the main cast) gave County Chief character Patton Oswalt the line to not-a-pedo-but-implied Officer Sminkle: “Bop the dude bros on the nose and turn them back into bags of fucking oranges”, well. He deserves an Oscar-shaped inhaler.

But it’s the ‘Morning Messages’ that are the punctum, if you would, as it were, permit me to apply Barthes to like, a scrabbled 3-second advert for vagina cleansing preceded by a man shrieking “all these bills!” Interrupting the broadly conventional story arc (emphasis on ‘broadly’), these deranged omens rip through the seams of the ever-imperilled, frantically-glorified dude bro myth, showing it to be nothing but the welter of absolute illogic.

Like trying to grab at snatches of a fever dream or look directly in the voidic heart of trauma, it’s difficult to remember any of these ads. My short-term memory would just short-circuit, and I’m even talking seconds after the ad had rent its terrifying gash. My memory is shit, but not quite that shit. It’s only through investigative re-play that I can describe to you the shot of a lady complaining about “lame coffee” followed by gremlin hand bursting through a wall towards a businessman cowering beside a pot plant. Grab some bags of fucking oranges, watch this film, and consider why the in-movie ad of a man plunging to death over a cliff after a screamed realisation he forgot his car keys is its genius metafictional kernel. Quoting Brent: “Cluuuuueeess!”

Other things I liked in films released this year:

- The pearly bleached achromatic grace of Embrace of the Serpent, the film that Fitzcarraldo is not

- The gorgeous costume design worn by Samantha Robinson in The Love Witch, with every stitch sewn by understandably over-controlling director Anna Biller

- Herzog describing UCLA’s corridors as “repulsive” in Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World

CJ Prince: I’ve decided to waste this opportunity by pointing out some stuff related to cinema from this year that I felt was worth mentioning.

Slamdance Roolz, Sundance Droolz: If you’re like me and know about the Sundance Film Festival, then you know it’s a flaming pile of garbage. Every year critics and people in showbiz flock to Park City, Utah and heap mounds of praise on top of terrible films, and every year we eagerly wait to be let down and pissed off that we trusted the opinions of people willing to spend thousands to travel to a cold city so they can sit in dark rooms for two weeks. But did you know that there’s another festival going on at the same time in Park City? The Slamdance Film Festival dedicates itself to profiling first-time filmmakers, but due to the hubbub of Sundance it’s often neglected by a lot of press outlets. 2016 was the first year I had a chance to delve into what Slamdance had to offer, and I came away both excited by what I saw and disappointed that little attention was being paid to them. Examples include Nathan Williams’ taut and impressive If There’s a Hell Below, Daniel Martinico’s baffling, hypnotic Excursions, and Claire Carre’s underseen/underrated sci-fi Embers, which I hope will get its proper due someday. They’re all some of the best discoveries I made this year, and did something to me that Sundance hasn’t done in a long time: it made me excited about independent cinema in the US.

Too Long: Blame it on Cannes: With the 3-hour Blue is the Warmest Colour and 3.5-hour Winter Sleep winning Palme d’Ors back-to-back, lengthy running times are back in style. This year, the festival saw lots of its competition titles pass by the 2-hour mark, but only a few of them justified their runtimes. Andrea Arnold’s plotless American Honey feels neverending at 160 minutes; Cristi Puiu’s Sieranevada shows that serious craftsmanship doesn’t mean shit when your 3-hour film goes on way longer than it should; and Toni Erdmann ambled about for over 2 and a half hours, to the point where even some of its biggest fans noted that it overstayed its welcome. But don’t let me limit this plague of overlong movies to just Cannes, as we also saw films like the 7.5-hour O.J.: Made in America, the 5.5-hour Happy Hour (which got a US release after a 2015 festival run), and Lav Diaz delivering not one but two long-ass films at 8 hours and 3.5 hours, respectively. It’s great to see filmmakers breaking free of the restrictions that duration brings, but Jesus Christ, I’m only one person.

TV is Cinema. Cinema is dead.: I tend to watch a lot less TV than I used to, possibly because movies have been getting so goddamn long, but I feel the need to point out some of my favourite television shows/episodes this year that got drowned out by the overabundance of new TV. I’ll get the obvious out of the way and say that yes, Black Mirror’s “San Junipero” episode is one of the best things I’ve seen all year, and the best Wachowskis film of 2016. Brett Gelman’s Dinner in America was ignored when it quietly aired over the summer, but it’s one of the sharpest and funniest takedowns I’ve seen of the insidious, pitying racism that tends to come from white, self-described progressives. Another deranged comedy from this year everyone should be watching: Jon Glaser Loves Gear, which starts out as a slightly absurdist reality show spoof before turning into something completely unhinged from reality, with its “Fishing” episode resembling a Lynchian Matryoshka doll (the less said about the episode’s surprises, the better). Finally, the second season of Ash Vs Evil Dead may have tanked its finale due to behind-the-scenes drama that made its way on screen, but the nine episodes before it were a series of one creative, hilarious, and disgusting set piece after another. It was a show that had no right being as entertaining as it was.

I liked other things, too. Here are a few of them:

- Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, for single-handedly getting me out of a brief depressed spell

- Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women, for making me forget about how bad Night Moves was as I shed tears over Lily Gladstone driving for 4 hours

- Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion, for out-witting the overrated and slight Love and Friendship while breaking my heart in the best way possible

- Mike Flanagan and Perry Blackshear, whose films Ouija: Origin of Evil and They Look Like People show a promising future for horror films

- The Cannes 2016 jury, for letting me know that even my worst life decisions are far from the worst decisions one could make

- That theatre marquee describing Moonlight as “A Frank Ocean song for the eyes,” for being the catalyst that made me give up on 2016 entirely

- This lovely website, for giving me the opportunity to write about the things that interest me (which is becoming narrower and narrower with each year)

Ali Schnabel: This year, I only watched fourteen films (yes, I am the worst, but you’ll have to rip my AFCA card from my cold dead hands). I have a legitimate excuse, because this was the first year of my Doctorate, but I’m still bummed about it. I can only think of four films out of that fourteen that I would put on a top ten (or four, as it were) list.

What’s interesting to note is that I saw all four of those films at MIFF. So, shout out to MIFF 2016 for giving me Personal Shopper, Happy Hour, Sonita and Helmut Berger, Actor. It is with a heavy heart that I accept my transition to the other side; to the troves of people who say “oh, I’ll probably only be able to get to a couple of films at the festival this year. Bit busy with assignment marking.” It’s bleak out here, y’all.