It is an unspecified time in the future, and people are ditching Earth to go live on shiny new planets, which are insanely far away but presumably have less traffic and fewer telemarketers. On a spaceship bound for one such Whole New World, a glitch in the system causes two passengers to be awakened from their hibernation early – 90 years early. Luckily the passengers, who happen to be Chris Pratt and Jennifer Lawrence, are very attractive, so they fall in love and then they don’t mind so much that they are doomed to live out their lives on a luxury spaceship. When a lot more things on the ship start malfunctioning, however, the spaced-out lovebirds are forced to take action in order to save themselves and the thousands of unconscious people on board.

This is the plotline for Passengers according to the advertising materials for Passengers. But, as has been duly noted by a number of critics, this is not exactly what happens in the movie. In a plot tweak that really fucks with the film’s moral compass, viewers find that it is only Chris Pratt, aka scruffy mechanic Jim Preston, whose hibernation is accidentally truncated. After a year of exploring the ship (cue the montage of Jim drinking and playing hologram DDR), our hero finds himself suicidally lonely. So he goes and wakes up Aurora (Lawrence), a beautiful writer with whom he has become obsessed in his isolation-induced funk. He sets about courting the disoriented young woman, a process which includes encouraging her to believe that her rude awakening, like his, was the product of a technological failure. What a meet-cute.

The film’s deep thought is this: what would you do if you found yourself in Jim’s terrifying position? In dramatizing this tricky but frankly stupid conundrum, writer Jon Spaihts seems to be attempting to say something about the fundamental sociality of the human race. However, any potential moral complexity is obliterated by the ham-fisted way the film works to justify all of Jim’s super creepy manipulations of Aurora, in order to ultimately valorise a grossly patriarchal vision of ‘love.’

From beginning to end, Aurora is thoroughly objectified: to start, Jim makes a ritual of ogling the dormant woman in her hibernation pod. He repeatedly watches her passenger profile video, where she speaks about her life and reasons for leaving Earth, and decides that she’s the “perfect woman.” So unconscious, so perfect, Jim! Then, Arthur (Michael Sheen), the “gentlemanly” android bartender at the ship’s luxe bar (What? Why?), and Jim’s only outlet for conversation (Oh, that’s why), also gets in on the objectification: he tells Jim that Aurora is an “excellent choice” after meeting her for the first time. Talking about women like they are cocktails is so gentlemanly, Arthur!

Once awake, Aurora is technically free to roam the ship, but she is relentlessly tracked and subjected to the male gaze. When Jim decides that he’s been in the friend-zone for long enough, he devises a ‘cute’ way to ask her out on a date: he modifies one of the Roomba-esque bots that rove around the ship to be controllable via remote, tacks on a camera, attaches a note suggesting dinner, and sends it off to find her. There’s something vaguely icky about Jim surveilling Aurora as she takes the note, unable to see him. The ick factor gets scaled way up, however, after Aurora discovers Jim’s deception. Rightfully furious at her captor, she attempts to avoid him – but without much success. From a control room, Jim broadcasts his sorry-not-sorry message all over the ship, the wall of screens behind him displaying Aurora from multiple angles as she goes for a jog. She can run, but she can’t hide.

Aurora isn’t even allowed to stay mad at Jim, because it’s right around this point that the ship’s glitches start to get serious. The imminent danger means that the two must work together, and Aurora’s wariness about joining forces with Jim gets framed as petty within the context of these much higher stakes. Like, oh my god, Aurora, just get over the fact that some random guy stalked you and then condemned you to die on this ship for his own personal gratification because now there’s a whole 5000 lives under threat and also he said he was sorry already! And besides, things were going really well between the two of you before you found out that he’d been lying to you for a year! And he’s Chris Pratt!

Spaihts further punishes Aurora for her anger by forcing her to put Jim’s life in danger to save her own, just as Jim put her life in danger to save his (remember, he was suicidally lonely). Realising that the only way to prevent the entire ship from exploding is to vent a certain fusion reactor, Jim discovers that the vent door is stuck and must be held open – a task that he bravely insists upon doing, even though he will almost certainly die as he is enveloped in the ball of fire being expelled. Aurora must pull the lever that will release the flames, but reveals that she is afraid of life on the ship without Jim. She had insisted that Jim pulling her out of hibernation constituted “murder,” but comes to find herself in a position where she too must put someone’s life on the line. Now she understands his original dilemma: living alone is scary, and also sometimes murder is ok.

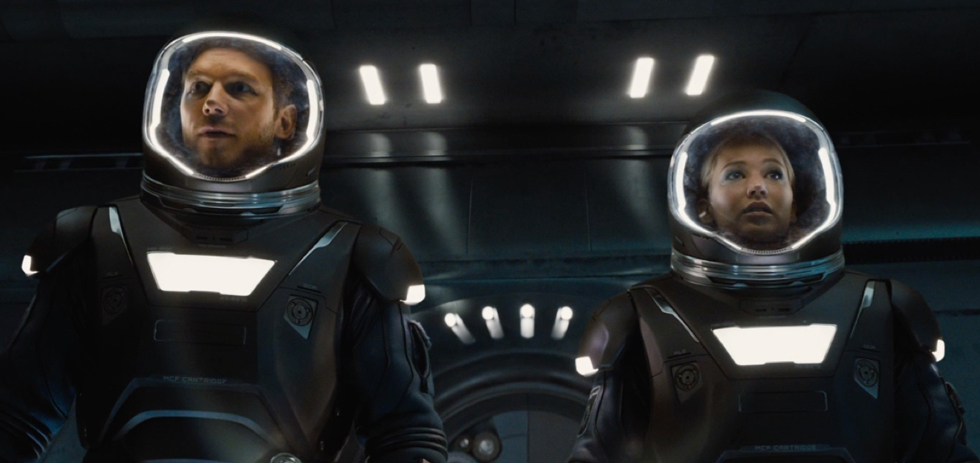

Of course, they save the day and Jim survives, and then the two of them live out the rest of their lives in blissful harmony aboard the ship, alone together 4ever. Yuck. Passengers treats its viewers like Jim treats Aurora, tricking them into thinking it’s just a fun escapist fantasy by misrepresenting its central premise. Once the viewer discovers the film’s hidden ethical snafu, they’re assured that it doesn’t even matter, because it turns out that Jim and Aurora really do ‘love’ each other and all’s well that ends well. Passengers could have been a great, claustrophobic horror film, if its second half was devoted to Aurora hunting Jim down; it could have been an interesting psychodrama if Jim was intentionally crafted as a morally ambiguous character, rather than having all his disturbing behaviour exonerated by the filmmakers. As it stands, though, it’s a dumb, poorly written piece of CGI spectacle, the eye candy on display sullied by the sexism that riddles its minimal plot.