January 24, 2017: “Movies are other people’s dreams,” says Lee Hayden (Sam Elliott) in The Hero. It’s a beautiful sentiment in a film that looks and sounds great, a lovely moment in a film about a film star that comprises a portrait of a man, using reality, film history, and dreamscapes. His is a nice thought, when there are so many films that – as noted in my first dispatch – find an horrific relevance in the current age. Dee Rees’ Mudbound, for example, depicts rural Mississippi in the 1940s, and its honesty stings sharply. It’s difficult to determine which is a more significant grief; whether it’s the horrific and widespread racism, the unrecognised postwar trauma, or the emotional and oppressive cruelty of husband towards wife. Terrific performances from Garrett Hedlund, Jason Mitchell, and Mary J. Blige make this depiction of struggle seem brutally, but also tenderly, real.

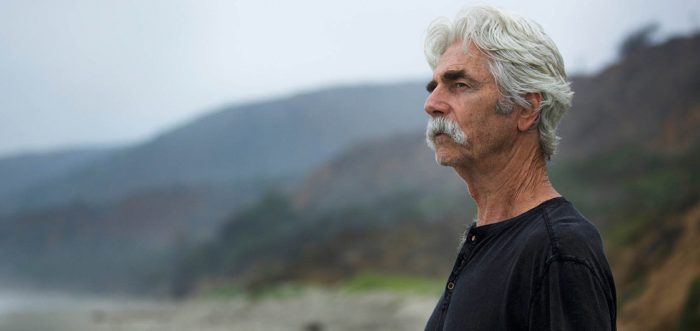

The Hero is about an ageing Western film star, played by Sam Elliott (and his moustache), who struggles with a nearly dried-up career and a possibly fatal cancer diagnosis. For much of the film, it’s unclear which is worse for Lee, and it refreshingly resists sentimentality for the most part. The overall plot is rarely surprising – a typical failed-father-and-husband narrative – but certain moments were full of energy and delight, and the scenes between Lee and his drug dealer pal Jeremy (Nick Offerman) recapture their clear chemistry from Parks & Recreation. I couldn’t help thinking, though, that it would be nice if we were done with the older-man-younger-woman-romance films, but here I certainly do give The Hero credit for Lee’s initial aloofness and discomfort with the issue. Some of the plotting is clichéd and distracting, like when Charlotte (Laura Prepon) spontaneously recites poetry to seduce Lee in the back of a limo. Sure it’s sweet, but I couldn’t help thinking of Slate Culture Gabfest’s recent episode in which the hosts mock the idea of having weaponised lines of poetry in your back pocket ready for such purposes. When they first meet, Charlotte tells Lee that he seems sad, and there’s a cut to Buster Keaton’s famous sad face on the television. Respect for the business, and film history, is what makes The Hero special.

Landline, the highly anticipated follow-up to Gillian Robespierre’s 2014 film Obvious Child, is a wonderfully energetic comedy with a heartfelt and believable exploration of a family dynamic. While the cinematography by Chris Teague is impressively engaging, the film’s strength lies in its script, written by Robespierre and Elisabeth Holm, which offers us three fully drawn characters in Dana (Jenny Slate), her sister Ali (Abby Quinn), and their mother Pat (Edie Falco). Dana and Ali constantly bicker, and they bicker with their mother, but all three also constantly reaffirm their love for each other. That the film offers three rich roles for women – as well as for each of their male partners, especially the father Alan (John Turturro) and Dana’s fiancé Ben (Jay Duplass) – makes it a pleasure to watch. There’s a moment, brought on by Pat’s marital despair and desperation, when she arrives home, immediately takes off her underwear, and sits on her husband’s lap. We have been given cues to understand that their marriage is under threat, so when they finish fucking and the refrain “but I’m lonely” echoes out from a television program, it is significant as subtle emotional commentary from the soundtrack. Despite all the romantic and emotional cheating, this is an incredibly tight family, alternately dependent and independent, and a collection of small intimate moments – rather than the overall story arc – are what makes Landline special.

Marianna Palka’s Bitch is a strange genre mash of horror, thriller, and domestic melodrama, that begins as a tale about a woman’s depression and domestic entrapment with her husband and children and ends as a tale of redemption for the pathetic and querulous husband. It starts off as a sharp black comedy but once past the opening scene, its abstract and emotionally interfering score immediately turned me off. It does develop and its cinematography can be impressive, and its final scenes are sincere and warm, affecting a slow-burning intimacy as the camera watches a renewal of understanding between the couple. If this came at the end of a different film, I’d like it much more, but here it was too little too late. Still, I’m glad I resisted the urge to walk out.

Not so with Janicza Bravo’s Lemon, an absurd comedy clearly trying to channel the work of Samuel Beckett (he gets a mention), with characters and dialogue whose deadpan humour drew laughs from the audience. It opens with an incredible shot, a digital clock flashing twelve o’clock amidst a cluttered, brown living room, as the camera pivots slowly. A very muted Judy Greer meant that my main reason for seeing this film let me down. The press notes begin: “Lemon: a person or thing that proves to be defective, imperfect, or unsatisfactory.” I left at the halfway mark.

I was really excited about Roxanne, Roxanne, a narrative feature of the biopic variety, about a young teen from the Queensbridge projects who becomes a rapping sensation as a teenager in the 1980s and, to put it simply, grows up too fast. The writer/director attempts to balance comedy with drama, and it begins with a great energy and beat, but this is quickly drained out. An interesting portrait of a time and place, of a black community in the projects, but for a film ostensibly about an artist, director Michael Larnell doesn’t show enough of her art: Roxanne Shanté’s (Chanté Adams) freestyle is often cut short as the film cuts to another dramatic scene. Shanté enters a relationship with the much older, charismatic (Mahershala Ali), and domestic violence becomes a key part of the plot, but it is not given enough dramatic attention. The film’s length is the problem here, because with its fantastic musical and editing rhythm, it could have moved much faster. Adams, though, gives a strong and stunning performance.

I haven’t watched a new television show in a while, and possibly a highlight of the festival was the opportunity to see three episodes of Jill Solloway’s new series I Love Dick – only the pilot has been released on Amazon to this date. It’s witty, hilarious, beautifully shot with an energy reliant on the chemistry between Kathryn Hahn, Griffin Dunne, and, as the third in their fantasy threesome, Kevin Bacon. This is definitely a show to watch out for, and is a great addition to popular dramatic fiction that understands female sexuality, and does not judge women (or anybody) for owning themselves and their bodies. As part of Chris’s (Hahn) dreams about a world that appreciated women’s art and filmmaking, the show features clips from Chantal Akerman’s Je tu il elle and Catherine Breillat’s Romance. Plus, it has the cinematic landscape of Marfa, Texas, to work with, so this show is pretty much exactly my thing.

As is A Ghost Story. It’s hard to discuss the plot and while it may have been revealed in film copy already, I don’t really want to try. In some ways it might be best to just say that it’s about a ghost who haunts an area of land for hundreds, thousands, of years, and by the end of the film is wearing a really dirty sheet. It’s a fascinating exploration of the passage of time, both as a concept of the universe and as a personal experience, and director David Lowery is not afraid of letting scenes, shots, and mundane moments linger, inducing a desire to leave and also enter the film space. It’s an emotionally violent experience, but the film itself contains no violence, only the fallout of it. Such a considered and considerate exploration of time is not something we have enough of in cinema; this is something very special.