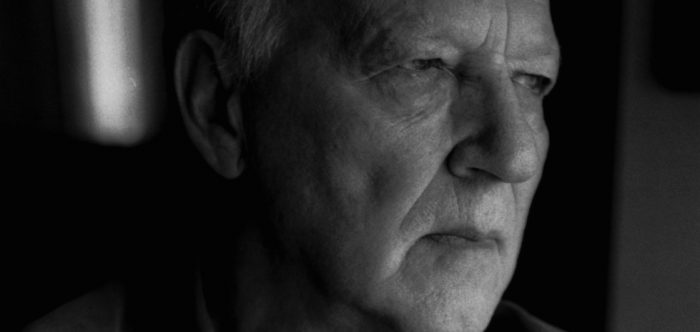

Werner Herzog’s dark paean to the internet, Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World, probes the rapidly shifting and expanding technological horizons of the 21st century. Ahead of the documentary’s run this week (15 to 22 Feb) at ACMI, we spoke to the inimitable auteur about the interplay of the virtual and the physical that propels our connected world, and how to best shield ourselves from its more insidious features. (The short answer: keep reading books. The long answer: see below.)

Lo and Behold didn’t come out that long ago, but a lot has happened in the world since—I’m thinking particularly about the election of Trump. There’s the idea that the proliferation of ‘fake news’ on the internet was central to his victory—

No, no, no, no, no. It was not essential to his victory. I think essential to his victory was the single fact that—and I know it from personal experience, friends in Boston, friends in San Francisco, for years, would talk about the “fly over”—I say it in quotes—what’s in between San Francisco and Boston, or Los Angeles and New York. The “fly over.” And I always complained; I said, “This is a cynical attitude.” This is the heartland you are talking about, the heartland of America. Those who have been neglected, those who have no real voice, those who have no coverage in the media. And all of a sudden, the heartland of America gave a fairly organized answer. It was what created Trump’s victory.

I would agree with that—but I think there’s still the issue of how the internet is able to spread information on an unprecedented scale, and almost instantly, and how there’s not yet a filter on that. Do you think that we should be working toward creating a filter or is the beauty of the internet in its absence?

Well, that’s something good, that there’s not much filter around. However, of course I’ve been in North Korea recently for a film on volcanoes [Into the Inferno, 2016], and there’s an almost 100% filter. The internet is only available for the political elite and for the secret service, and for some university institutions, but that’s about it. So it’s not a cloud that is around us, like particles of mist—it’s actually servers, and routers, that are land-based and you can shut them down. And so, at the same time, we have to be cautious that we do not start some sort of censorship informed by complete political correctness. Something is good about the anarchy in the internet. We simply have to—instead of asking for the censor—we should rather be developing our own filters. Every single one of us. Where we would recognise, ‘Oh, this is junk mail and they’re just trying to make you download a Trojan and read your emails,’ and things like that. But for that, you have to go and do some old-fashioned thinking. You have to go read books, for example, and not just read tweets and Facebook entries. That’s what is real and necessary.

I think that’s an important idea in the film: it’s not about whether the internet is ‘good’ or ‘bad’—that’s the wrong question—but how to develop an ethics around it. It’s a tool, and at the moment we’re still in the infancy of understanding how to use it.

There’s a certain intelligence that we have developed by walking the streets in heavy traffic. We learn because of experience with traffic, how to behave and how to cross an intersection with the necessary caution.

But, of course, there are casualties.

Yes—and there will be many more casualties of the internet coming at us. And yet we cannot stop it unless we take an attitude like North Korea.

Speaking of which, that footage of North Korea in Into the Inferno is incredible. I wondered if you had any interest in going back, or if you’ve captured what you wanted to capture.

I was only allowed to capture the collaboration between Cambridge University and North Korean scientists studying the volcano. However, I talked—I bamboozled them into letting me shoot much more—the subway station, shooting the kindergarten, the stadium, and so on—but that was my street wisdom, to persuade them.

It’s something that comes in handy.

Well, sometimes I have to. But the only thing which would bring me back… I sent a message to the young leader, Kim Jong-un, to speak on camera about the importance for the Communist Revolution, or Socialist Revolution, in his country and the importance of the dynamics of the volcano, the mythology of the volcano. If I get invited to speak with him on camera, I would return. Otherwise, I wouldn’t.

I would look forward to seeing that, if it ever became a possibility.

No, I don’t think so. But that would be the reason to return.

It is quite an unpredictable nation. And Kim Jong-il, as you mention in Into the Inferno, was a huge film buff, although I don’t know if Kim Jong-un shares that.

I know the father wrote screenplays, and was a film buff. But North Korea in my opinion is not really totally unpredictable. There is a very coherent worldview—it’s quite apparent—but nobody cares to look into that. And there’s a very coherent sort of politics of, let’s say, self-reliance, including self-reliance in terms of military achievement, in weapons.

Yes, there’s a name for that policy—

Juche, yes. Anyway, I can only say there’s a very coherent worldview, and we’d better look into that. Demonising the country doesn’t get anyone anywhere.

Well there’s definitely a link there to what’s been happening in America.

Right, you’d better study the enemy, study them well.

In Lo and Behold, Lawrence Krauss suggests that if the internet were to go down, people would not remember how they lived before, and that he probably wouldn’t survive. I know that you’re relatively ‘unconnected’ on a personal scale, but we’re all reliant on systems that are deeply connected. Do you have your own contingency plan for the potential internet apocalypse?

No, no, I don’t have a bunker. That is the last thing I would like. But I would probably be a better survivor than Lawrence Krauss—because I have travelled on foot, I’m good in a jungle, I’m good in the snow, I’m a good hunter, I can make fire without matches… and a few other things. I would be a fairly good Neanderthal.

Talking about survival in hostile scenarios—in your conversation with Elon Musk, you gamely offer to go to Mars. I wanted to ask if you feel personally invested in the expansion of human life beyond this planet.

No, it’s curiosity, of course. Elon Musk is an extremely shy man. Very introverted, very taciturn. And just to make conversation lively, I challenged him. I said, “Well I would come along.” Of course I would come along to Mars if I have a camera along with me, and I could send images back to Earth. Otherwise, colonising Mars, I think is an ill-conceived idea. We have nothing lost up there. Even building a colony at the bottom of the ocean would be a thousand times easier. We should rather look into improving the habitability of our planet rather than improving or creating the habitability of Mars or whatever—Pluto, or Alpha Centauri.

In the film, Lucianne Walkowicz espouses a similar view. She suggests that moving to Mars is not the solution to problems we’ve created on Earth.

It’s an ill-conceived idea. We should rather look out for making our planet more habitable.

I’m a good hunter, I can make fire without matches… and a few other things. I would be a fairly good Neanderthal.”

After watching the film for the first time, I found myself wondering where the material on social media was… for many, these platforms are such a central part of the internet. Did you feel the topic was too worked-over, or maybe too prosaic?

You see, everybody knows about it anyway, and everybody’s into it. I do not have to describe it, and I do not have to go into it. I’m asking much deeper questions—”Does the internet dream of itself?” for example. Some very disquieting sort of things. A few elements, for example, like self-driving cars, I’m fairly quickly going over it, because everybody talks about it and it’s described very well by the media nowadays. I left, of course, a few things out, and a few things, I couldn’t achieve in the short time. Like for example, I would be fascinated by this artificial currency, Bitcoin—things like that. So there’s maybe other aspects that are quite fascinating but the film is not encyclopaedic. The film is not pedantic. It would have made a five-hour film.

You’re right, social media is something that we all know about, and that has been covered, but at the same time I think it has very disquieting aspects. And in the film you do touch on the idea of the avatars that we create for ourselves online, such as the “malevolent druid dwarf.” When we craft these identities, in games or on social media, we’re projecting a curated self. I wondered if you had any thoughts on our culture’s increasing obsession with our own image—this sort of hall of mirrors that we’re creating.

Well, it is not new, but it is much more pronounced nowadays because we have Facebook and all the self-presentation has become different. It has become more obvious, and it’s more organised, embellished, in artificial selves. And it’s fascinating because so much self-representation is on the internet. Fashion, for example. The kind of dress that you wear has become unimportant. And when you look at the very, very big fashion distributors—and my friend is one of these people, who is very, very deeply involved in the garment industry—she tells me, because of the permanent self-representation on Facebook, for example, it doesn’t matter anymore whether you wear a wonderful suit, a wonderful evening gown. It’s enough that you wear a t-shirt.

In what sense?

Whatever it is, self-representation is on Facebook and not so much in your dramatic entry when you go to the Opera House and wear a wonderful evening gown. That becomes not important. It’s a different kind of self-representation. And for me it’s kind of bizarre, because you find me on Facebook, but it’s fake. There are imposters out there—I have at least 30, 40 doppelgängers. I’m on Twitter—it’s not me, it’s an imposter. You find voice imitators; you find me doing counselling to broken hearts… it’s all not me. I have the feeling it’s my unpaid bodyguards out there. Let them do battle.

Do you remember your first encounter with one of these doppelgängers?

I think it was mostly voice impersonators, and then, I was told by friends, “Have you seen what you said on Facebook and all the responses?” I said, “No.” I haven’t seen them until today, I can’t even access it, because I don’t have a Facebook account. I get it second-hand. And of course, some things went viral, like “Werner Herzog’s Letter to his Cleaning Woman.” After half a line, you can already tell this is the wildest form of satire. And there were really wild responses against me, this creep who doesn’t treat his cleaning woman well. And number 104 of the commentaries notices that the author of this letter even outs himself: “Werner Herzog’s Letter to his Cleaning Lady” and then under it, by Scott Fellow. Yes, everybody can see it’s somebody else, but people do not understand satire anymore because they do not understand text in a wider context, which you only learn when you read books. It’s interesting that people do not understand context anymore, because there’s not enough reading.

In my Rogue Film School, which is a guerrilla-style, wild, sort-of anti-position against what you normally see done in film schools, I have a mandatory reading list—part of it poetry from Roman antiquity, it’s the Warren Commission report on Kennedy’s assassination, it’s Hemingway, and also other things—because even young filmmakers do not read anymore, and that’s a very serious thing.

To jump back to the idea of these selves of yours, that exist apart from you and which you can’t even access in some cases—do you have thoughts on a future where you won’t exist but your doppelgängers will?

They are ephemeral. You see, they follow very, very short-lived little trends. They’re very ephemeral, and what really has substance is going to remain. I remember, about a good half year ago, I made some sort of funny remark about Pokémon, and everybody worldwide was into it, and people were completely appalled, and there were hundreds of thousands of comments on me and Pokémon. Today, nobody speaks about it anymore, and it was only a few months ago.

I guess people stopped playing Pokémon.

Yes, it vanishes like a quick ephemeral fad. And you see why my presence in the internet is so intense, and why I’m so noticed, because the internet collectively knows about all the fake personas, and all the embellishments, and collectively the internet seems to have a sensory organ for authenticity. They know I have moved a ship over a mountain, and they know I have been shot during an interview, and they know I have cast a film with midgets, and they know I have hypnotised an entire cast of actors for a film, Heart of Glass. And I have travelled on foot from Munich to Paris in winter, and on and on… so authenticity is something that sticks out like a sore thumb.

Well I guess that’s a good note to end on. It’s been an honour and a pleasure speaking with you.

Thank you very much.

Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World screens at ACMI from February 15-22.