Queensland Film Festival and the Institute of Modern Art (IMA), in Queensland’s Fortitude Valley, have partnered to screen a series of experimental film programs in 2017. The IMA, an independent arts centre established in the mid-1970s, was a venue for the inaugural Queensland Film Festival in 2015.

All three of the announced programs are concerned with landscapes, whether physical, digital or mental. The first program strand, Sheltering Islands, screened in February this year. The second, Speleogenesis, screens Saturday 29th April. The final program, The Unity of All Things, screens on June 3rd.

In this feature piece, Phoebe Chen and Conor Bateman write on the films featured in the first two screening programs, Sheltering Islands and Speleogenesis.

Program One – Sheltering Islands

Phoebe Chen: For some, “experimental film” has become shorthand for “difficult viewing”. Difficult is slow; difficult is lacking discernible narrative; difficult is the absence of cues that ordinarily structure our attention. With its emphasis on landscape, the first of the experimental film programs, Sheltering Islands, has tasked itself with communicating the complexities of colonial historiography without relying on conventionally relayed subjectivity. In islands, there are the promises of alternate histories, timelines we need actively seek out lest they vanish under the weight of dominant global narratives. The films in this series begin at a perceptual distance from the islands, then gradually burrow beneath their topographies into caves, forests, vestiges of colonialism.

The program opens with Christopher Becks and Emmanuel Lefrant’s I don’t think I can see an island (2016, pictured above), a series of brief sequences featuring an unidentified island shot on 35mm. The footage mostly consists of disquieting, red-tinted negatives, filmed by an aerial camera panning land and sea, roaming through low cloud. Becks and Lefrant set the images to ominous ambient sounds that further distort whatever coherency the grainy images manage to convey. As an opener, the film functions as an obvious semantic primer. What are we looking at, it asks us, behind all the obscure visual and sonic planes? Formal inquisitiveness is a useful mindset to carry throughout this series, as questions of construction float to the fore.

The remaining three films address the colonial histories of their respective islands, each with a distinctive syntax. Joana Pimenta’s An Aviation Field (2016) is a surreal 16mm mapping of a landscape, dreamed out of existing histories. Pimenta offers magnificent vistas of Pico de Fogo, an island in the former Portuguese colony of Cape Verde, off the West African coast. Colonial intrusion is signaled in visual and aural motifs of aviation. Aircraft, it seems, have now replaced the conquerors’ ships that once came gliding across the sea. Inevitably, new heights have restructured our regimes of looking and moving. Pimenta oscillates between the disorderly lines of nature – mountain slopes, creeping fog – and the hard angles of nondescript urban sites. This composite landscape is a ghostly one, entirely lacking human presence save for a long shot of two figures traversing Fogo, so distant and rhythmic in their movements that they could easily be machines, trailing dust or smoke. There are no obvious temporal demarcations in the film, as Pimenta doesn’t seem interested in representing or metaphoricising chronology. In one shot, a rotating camera captures silhouetted mountains in possible time-lapse, the sky fading from the lucid orange of dusk to a deep purple night. The moment is revealing – Pimenta tells us of Fogo’s forgotten past with poetic rather than narrative intent. It’s fitting that poetry also traffics in the otherwise-unsayable.

The excavation continues in Samuel M. Delgado and Helena Girón’s Burning mountains that spew flame (2016). Briefly, we rove the grassy surface of an island, somewhere in Spain (likely Tenerife), until a voice issues a warning through coded whistles (and explanatory subtitles) –“Watch out! It’s getting closer!” From here, we burrow far down into the island’s volcanic tunnels. Delgado and Girón situate us at a temporal crossroads with a combination of analogue and digital footage, some shot on expired 16mm colour negative, and some in 4K. A vivid tactility links the different media – extreme grain from the expired film flits across shots of cave interiors, distorting already ambiguous shadows into fields of colourful static. The 4K footage substitutes film physicality with the haptic immediacy of intensely detailed, high-resolution images. These sequences play out like a secret life of rocks, camera drifting across the textural minutiae etched onto these formations by unwitnessed forces. In these tunnels, there are intimations of the illicit, the mysterious. These frames often feel emptied of empathetic objects, which makes it difficult to anchor our perspective. If these tunnels house contraband histories, we have to consider the privileged site of our gaze. But that’s precisely the challenge here – it’s only through the self-reflexivity of the cameraperson’s presence that we are reminded of our subjectivity.

The final film in the program, Alexander Carver and Daniel Schmidt’s The Island is Enchanted With You (2014), makes for a wild, tonally divergent conclusion. This is the most narrative-driven of the four, peopled with actual characters propelling actual events. Even so, there is no latching onto predictable subjectivity here. The island in question is Puerto Rico, and the main narrative strands a smallpox vaccination scheme, enacted in 1803 by one Dr Javiér de Balmis, and the mass production of pharmaceuticals in 2014, subsidised by the US. Carver and Schmidt humorise the colonial gaze by presenting the island as a sentient, sexual object. The island’s consciousness is embodied in a bizarre range of metonyms – multiple actors (sometimes in the same scene), a voiceover, and of course, the glowing cartoon of a headless, naked male body with a face embedded in its torso. Not that the island’s seductive, natural abundance needs further emphasis, but Carver and Schmidt lay it on anyway. The film is, appropriately, very wet and blue – water is always present in some form, from the soft lapping of the ocean to thundering waterfalls and their plunge pools. The island too fertile to be rejected. In these scenes, colonial greed is translated as lust; lust is hyperbolised through humour; humour functions to destabilise power dynamics.

Program Two – Speleogenesis

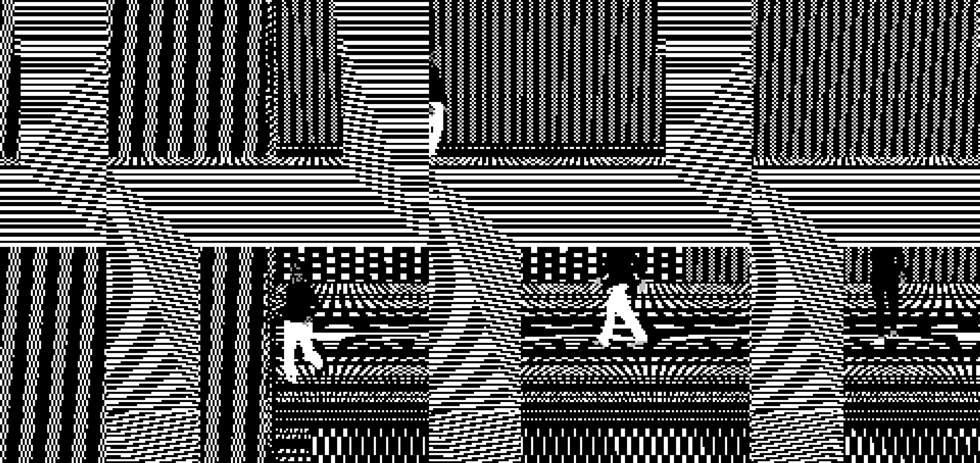

Conor Bateman: The second program, Speleogenesis, moves from the island to the mainland (and the mainframe), with works fixated on networks: physical tunnels and caves, digital connections, and mental mappings (referents, words, leaps in logic). The first film, Peter Burr’s Pattern Language (2017) signals a sharp move away from the celluloid stylings that marked the Sheltering Islands series. We open on what appears to be a geometric parsing of television static; shapes move along parallel lines at a mechanical pace, one set by the minimalist beeps and boops of John Also Bennett’s musical score. There’s an uncanny distance between the analogue origins of the scrambled visual signal and its computer generated facsimile, one that feels less at home in the world of cinema than video games. Fitting then, that Pattern Language emerged from the production process of Aria End, an experimental game that situates the player in “an endlessly mutating death labyrinth”. The game, much like Pattern Language in a gallery setting, is a multi-channel presentation. A series of screens envelop the player/viewer’s field of vision, the sense of containment a fascination within and without the image. In the film, a fixation on patterns gives way to a palpable voyeurism; at one point we take the perspective of surveillance cameras spinning across a room, watching a faceless person move their hand through a miniature constellation. This doesn’t mean the film jettisons the game’s labyrinthian ambitions, though, with a recurring sequence set in what looks to be the insides of a shopping mall, rendered as an endless series of hallways populated by an unceasing stream of people, mindless drones who themselves become indistinguishable from their surroundings.

Where Pattern Language keeps us contained, Anouk de Clercq’s Thing (2013) sends us careening off into the distance. The digital ruins of an imagined city, floating in space, are less the titular thing than a prompt to consider the idea of ‘things’ as they relate to one another. A disembodied voice, apparently the architect of these virtual constructions, delivers philosophical ruminations in a tone refusing to commit completely to drollness. There’s a nakedness to the architect’s buildings, not due to their apparent ruin but rather their hollowness. Over time, the clustered pixels begin to resemble less imprints of buildings (which, as 3D scans, they are) than structures caught in a broken game, where a player can pass through the world, which itself hovers precariously over an enormity of nothingness.

Colossal Cave (2016), from Graeme Arnfield, is concerned with game-making of a different nature. The plot, though relayed through entertaining, matter-of-fact subtitles, is a historical chronology. We hear of William Crowther, a computer programmer whose Kentucky caving adventures with his wife Pat led him to create Colossal Cave Adventures in 1976, a command-based computer game widely considered to be the first work of interactive fiction. While this story is about the birth of a genre of computer game, the visual track in Arnfield’s film refrains from both digital animation and the gleefully kitsch era-specific camerawork found in Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess, instead only showing footage of contemporary cave exploration from amateur cavers. The use of found footage and audio echo the way in which the actual Kentucky cave network, via the proliferation of games, became primarily an idea of landscape, one fought over by and rewritten in the image of whoever happened to play through it.

Just as in the first program, the final film in Speleogenesis is the most narrative-driven, though it could have used some of The Island’s enchanting abstraction. Entangled (2014), from Italian filmmaker Riccardo Giacconi, presents a series of portraits of townsfolk in the Colombian city of Cali. He connects these through imagery rather than spoken content; shots are linked by leaps of logic, visual similarities or shifting perspective within the one space. It’s the mapping of a train of thought, as twisty as the anecdotes our various storytellers tell. Among them: the sudden appearance of a lion and the eerie disappearance of a cow. Underpinning it all is the notion of quantum entanglement, which a young physicist explains to camera. Fascinatingly, a near-identical sequence to this one is in Kirsten Johnson’s documentary memoir Cameraperson. Where Johnson uses the quantum entanglement anecdote to emphasise the fundamental connection between decades of footage (the presence of her as cinematographer), Giacconi uses it to needlessly clarify the links between his shots, which are almost always immediately clear. Still, as a slice of life tetraptych it is unique and its place in this program returns the digital connection to the physical. That seems an appropriate trajectory, as the final program in this series, screening at IMA in June, features Alexander Carver and Daniel Schmidt’s feature The Unity of All Things (2013).

The second experimental film program, Speleogenesis, screens for free on Saturday 29th April at the Institute of Modern Art. For more information you can head to their website here.

The third program strand, The Unity of All Things, screens on June 3. We will be covering the films featured in that program in a later piece.