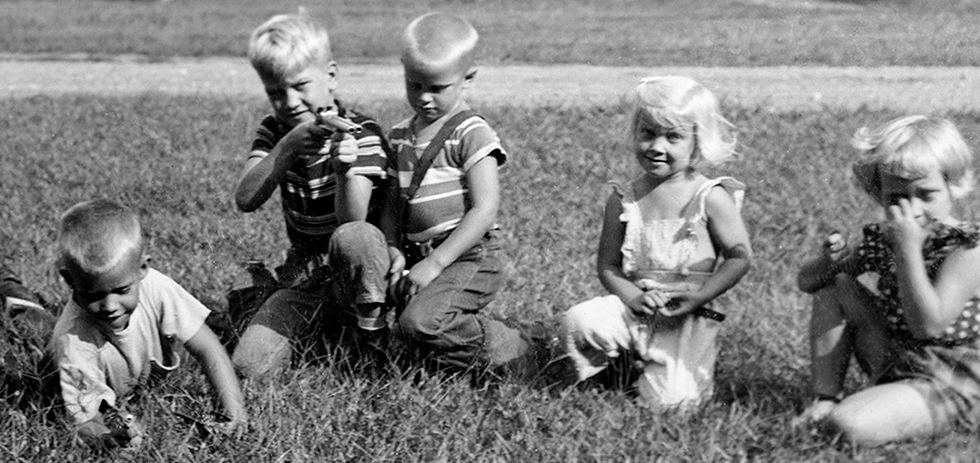

“I think every time you do something, like a painting or whatever, you go with ideas, and sometimes the past can conjure those ideas and colour them,” muses David Lynch. “Even if they’re new ideas, the past colours them.” David Lynch: The Art Life oscillates between past and present; stories from Lynch’s early life and career ensconced within a portrait of his contemporary fine art practice. This meditative documentary indicates the evolution of that (moody, contorted, dreamlike) sensibility now so instantly recognisable as ‘Lynchian,’ grounding it in a personal history — the past shown to inform the present. In between sequences showing Lynch at work in his studio, viewers are offered glimpses into the septuagenarian auteur’s youth, from his apparently idyllic childhood to his art school days in Philadelphia, cutting off at the beginnings of his directorial career. Lynch himself narrates (in a suitably episodic and enigmatic fashion), his recollections vivified by snippets of old home movies and photographs. Images of his paintings and photography are also mobilised as illustrations for his stories — the present colouring the past. Naturally, time moves both ways in Lynch-land.

This is not the first time Lynch has been the subject of a documentary. The Art Life is preceded by 2007’s Lynch (one), which is loosely structured around the making of INLAND EMPIRE (2006), and presents ‘Lynch, the filmmaker’ in action: he jokes with — or reprimands — his crew and collaborators; he delegates, deliberates, directs. The film is a freewheeling peek ‘behind-the-scenes,’ in which Lynch is positioned at the centre of a complex creative organism. Although The Art Life features some of the same crew, it is in many ways a counterpoint to Lynch (one), both in scope and tone. Here, Lynch is portrayed as a solitary figure: the ‘contemplative artist,’ secluded in his studio/residence nestled in the Hollywood Hills. The film’s only other human presence (aside from those who appear in the archival materials) is Lynch’s young daughter Lula, who makes intermittent cameos, more often playing alongside her father than with him. Whereas Lynch (one) is a lively and exploratory bricolage, The Art Life is more polished and cohesive, and the Lynch it portrays more composed, his location fixed.

Lynch’s elliptical story-telling mode lends the film a hypnotic quality, his measured voiceover complemented by a liberal use of slow-motion. Sometimes shown labouring over a large canvas, smearing viscous paint around with a gloved hand, sometimes in repose, gazing into the distance — and smoking, always smoking — Lynch’s movements are considered, imbued with stoicism, often shown in close-up. A kind of claustrophobia attends the scenes depicting Lynch’s creative process: his world seems circumscribed by the boundaries of his studio. And yet, the studio is also the point of departure for his excursions into the past, memory becoming a mode of transportation. As much as The Art Life is concerned to show how the past is contained in the present (and perhaps vice versa), it is also premised on the assumption that small things contain much bigger things — a tighter focus can produce an expanded vision.

Lynch describes the world of his childhood as extending only a few blocks from his house – but those few blocks, he asserts, contained “huge worlds.” Coming from a man whose films are all, in one way or another, journeys inwards, this ostensibly paradoxical statement makes sense. His narratives are often inaugurated by a slow zoom into a darkened orifice – e.g. the severed ear in Blue Velvet (1986) — which acts as a portal into a seamy and uncharted realm: an ‘inland empire,’ if you will. In The Art Life, directors Nguyen, Neergaard-Holm and Barnes present a restricted view of their subject, eliding his Hollywood fame and his involvement with Transcendental Meditation in order to concentrate on the relatively ‘small’ topic of his fine art practice. Of course, Lynch’s “art life” colours and contains his other lives, past and present, those “huge worlds” lurking below the surface of this minimalist but compelling film.

Around the Staff

| Luke Goodsell |