To call David Lynch’s Twin Peaks a cultural phenomenon feels too feeble a descriptor to capture just how deeply this television series about a murder mystery in small town America has sunk into the popular consciousness. Like much of Lynch’s work in feature-length cinema, it is a screen artefact that demands — and at times even mocks our near-impulsive drive towards — in-depth criticism. Dedicated fanzines such as Wrapped in Plastic (recently rebooted under the new name The Blue Rose) were launched as early as 1992 , and Twin Peaks tourism — honing in on the locations used in the series such as Snoqualmie, North Bend and Fall City in Washington state — is still a micro-industry in its own right.

At the time of the series’ initial broadcast in 1990, Lynch had built a reputation on films like Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980), and Dune (1984), and would rise to the status of weird-yet-accessible cult icon with Twin Peaks arriving on the back of Blue Velvet (1986) and 1990’s Wild at Heart (which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes). Twin Peaks first aired a month after the release of Wild at Heart, amplifying excitement levels around the filmmaker’s work even further. Yet what remains most fascinating about Twin Peaks and its popular appeal is how it has transcended its zeitgeist: 27 years after it first appeared, a mood of outright hysteria among fans surrounds the series’ reboot, a 16-episode continuation of the story featuring some of the key original cast that will stream worldwide from May 21.

Author Franck Boulègue’s continued fascination with Twin Peaks is a welcome deep critical exploration of this phenomenon, not only in regards to the inner workings of the series itself, but how it fits into Lynch’s broader status as an artist and filmmaker. His second book on subject,Twin Peaks: Unwrapping the Plastic (2017), has recently been released, supported by a detailed blog that offers a diverse range of critical ways into the show. Boulègue seeks not to ‘solve’ the puzzle of Twin Peaks, but rather to deepen the terms of our engagement. He speaks to us here about the work.

You and I initially crossed paths professionally in an altogether different professional context than film criticism: that of dance studies. I confess a real fascination with the intersection in your work (often with your regular collaborator Marisa C. Hayes) between dance/choreography/movement and cinema. There is something about Lynch’s work — not merely Twin Peaks, but I think across the board, from the earliest shorts right through — that really privileges the notion of bodies-in-movement: those beautiful slow, deliberate gestures that mark some of my favourite images in his work. What do you think more broadly about the relationship between Lynch’s filmmaking and movement and/or choreography?

I think it is fundamental to remember the etymology of the word cinematography: the art of writing movement. As early as the first films, cinema, dance, and choreography have been strongly linked, from the Lumière Brothers and other early filmmakers’ Danses Serpentines shorts to Méliès’ pantomimes and dance films, evolving at the beginning of the 20th century into Germaine Dulac’s Thèmes et variations and René Clair’s Entr’acte. In a way, one could even go as far as saying that cinema was invented to film dance.

In Lynch’s case, one has to keep in mind that he started his artistic life as a painter. But then, he explains, one evening he stood back from a painting he was working on and had the following revelation: “I’m looking at this figure in the painting, and I hear a little wind, and see a little movement. And I had a wish that the painting would really be able to move” .1 His films are really paintings in motion, which generates an obvious relationship to the world of dance and choreography.

Do you think that is specific to David Lynch?

I would argue that it’s impossible to be a good film director without also being, to some degree, a good choreographer. The movements of the actors and of the camera are so important in cinema that anyone who does not think choreographically is doomed to fail as a filmmaker. Lynch definitely has a choreographic sense: dance, movements, gestures play such an important role in his films — from the idiosyncratic way Henry walks in Eraserhead to the opening dance sequence in Mulholland Drive, without forgetting Sailor and Lula’s power dances in Wild at Heart. In Twin Peaks, several characters are seen dancing — Audrey Horne at the RR, Benjamin Horne and the dance of Louise Dombrowski with her flashlight, Leland Palmer and his sudden choreomaniac outbursts after Laura’s death. Beyond that, important and recognisable gestures and movements are performed by various characters throughout the series and film — the shaking of hands which seems to prefigure the opening of the Lodges, near the end of the show, to name just one.

At one point in Twin Peaks: Unwrapping the Plastic you talk about even the natural movements in the opening credits being a kind of choreography (the waterfall, chimney smoke, etc.)…

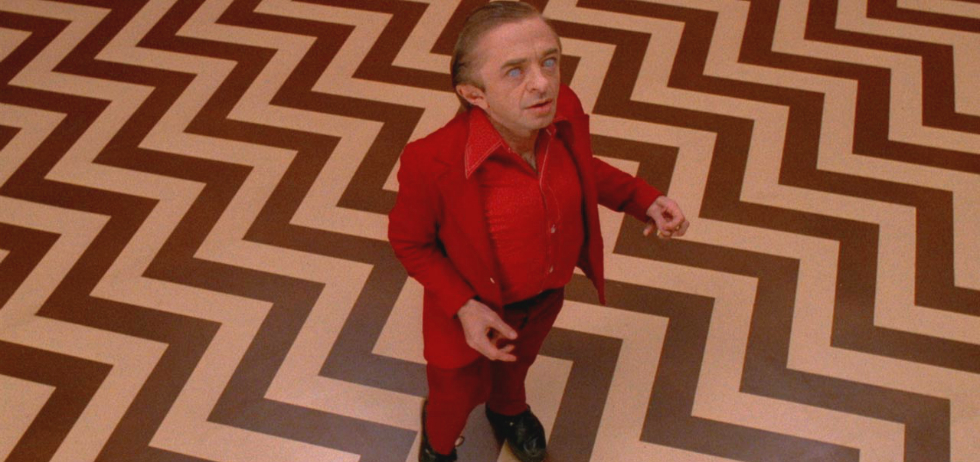

This interest in choreography is not limited to people in motion, it also includes the movement of the world at large, both natural and industrial, as exemplified by the opening credits of the series. But it is of course the dance of The Man From Another Place that is best remembered by audiences, because it was shot backwards, which gave it a surreal quality. I think it’s appropriate that this specific dance remains the best remembered because in the Twin Peaks universe, the Red Room and the Lodges are closer to the roots of the mythological cosmic tree on which the town of Twin Peaks is built. The Lodges are the place of origin, the place of unity (to borrow the monistic vision of the universe developed by Transcendental Meditation) from which emanates all vibrations that set things in motion.

So you can see traces of Lynch’s interest in Transcendental Meditation in Twin Peaks through these kinds of movements?

These wave-like vibrations can actually be visualized in the chevron motif on the floor, and they indeed permeate life in Twin Peaks as a ripple effect. Indeed, everything is interconnected in Lynch’s conception of the world. He uses the concept of the “unified field” to describe this phenomenon, a term originally coined by Albert Einstein, but which, in Lynch’s version, is colored by spiritual considerations from Transcendental Meditation.

This notion of vibration is found repeatedly in esoteric texts (even up to the psychedelic “good vibes” of the ‘60s) and it plays a fundamental role in Twin Peaks in particular, in addition to Lynch’s filmography at large. His universe is a continuous process, from unity to vibrations, and from vibrations to choreography. He even went so far as to direct a (dreamy, of course) dance film of his own entitled Ballerina in 2007. Lynch likes to explore what’s beneath the surface, perhaps he calls on dance and movement in order to bypass language and everyday dialogue to find a deeper, more primal form of expression through the movement of the body (here I’m thinking of Lil’s dance in FWWM, among others). Walter Benjamin discussed how the body is capable of expressing the unconscious, for a filmmaker like Lynch obsessed with dreams and interior worlds, movement is the perfect tool for this.

So speaking of obsessions: why Twin Peaks? What lead you here, 27 years after its first episode went to air?

Like Dale Cooper, who first entered Twin Peaks more than a quarter of a century ago and got stuck there, I never really left this universe myself. It has been present with me at every turn of my life, and I have watched the series and film so many times that I have actually stopped counting (more than 50 times, I believe, in the case of Fire Walk With Me). Both the series and the film are like a bottomless well. No matter how many times I view them, I always discover something new. Twin Peaks is a gigantic puzzle, so rich with material and possibilities. In a sense, I have always thought of myself as the “1” at the end of the population of “51,201” that’s mentioned at the bottom of the “Welcome to Twin Peaks” sign. It was obvious to me that I would have to address Twin Peaks in my writing sooner or later, and the book Twin Peaks: Unwrapping the Plastic constitutes the first step for me in this process of making sense of the series and film.

But you had previously worked on a book about Twin Peaks?

Marisa C. Hayes and I edited a book entitled Fan Phenomena: Twin Peaks in 2013, a collection of various texts written by fans of the series from all around the world. But that project was mostly by the fans and for the fans within a format that Intellect Books proposed, and I felt like I had to address several themes that had been left unexplored due to the format of the book, perhaps less from a fan studies perspective and more in keeping with various aspects of film analysis.

There is a vast mythological background to the Twin Peaks universe that begs to be approached from a variety of angles. I am tempted to say, to paraphrase David Lynch, that there is a surface story to Twin Peaks that revolves around the murder of Laura Palmer, but that if one wants to catch the big fish, the ideas that fuel this surface story, one has to dive deeper towards the depths of psychoanalysis, surrealism, transcendental meditation and theosophy.

What has made Twin Peaks so enduring, for you personally and professionally, and for contemporary audiences today?

Especially now that the show is set to return to the small screen for a third season, the mark it has left on contemporary culture has continually brought new generations of fans to the show, people who have grown up with this mythology that has influenced so many films and television series since it first aired, from the The X-Files to True Detective or Bates Motel, or Lake Mungo to Donnie Darko in cinema. Also, the fact that Twin Peaks ended on a cliffhanger probably helped foster the cult status of the series. Since it never received closure, especially not with the prequel film Fire Walk With Me, public interest never dwindled. And now that we are witnessing a great conjunction of opportunities with this new wave of auteur television — a conjunction somehow similar to the cosmological one that opens up the doors to the Lodges in Twin Peaks, when Jupiter and Saturn meet in the sky — all the elements are in place for an exciting return to this universe.

Twin Peaks is often brought up as a key example of what is now broadly (and somewhat hazily) considered “cinematic television”. In many instances it is considered really the first of the kind of “auteur” TV linked often to later HBO produced series like The Sopranos, but including things like Lars von Trier’s Riget. This in some way feels like a narrow history to me because it really ignores what came before Twin Peaks, such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Ingmar Bergman’s work for television. But what in this bigger historical picture do you think made Twin Peaks so special in this historical narrative of “quality” television?

I think the answer lies in the dual nature of Twin Peaks itself. Contrary to the various series you mention above, all directed by a celebrated filmmaker, Twin Peaks not only had David Lynch at its head, but also Mark Frost. While David Lynch brought the “auteur” side of things to the show, Mark Frost brought a more traditional narrative approach and an intimate knowledge of the workings of television along with him. He was already well established as a scriptwriter for several successful shows, notably Hill Street Blues, and knew how to capture and maintain the interest of a wider audience. The works that Fassbinder, Bergman, and von Trier (who acknowledged that Twin Peaks was one of the major influences on Riget) directed for TV were all excellent in many ways, but they did not, as far as I know, have the same cultural impact over the population at large that Twin Peaks had (and still has, more than 25 years after it first aired).

Twin Peaks is “quality” television in the sense that it is “cinematic television”, but it also borrows some of the specificities of the televised medium narrative to achieve its aim of gathering a large audience, including tools often shunned by some who might associate them with the lowbrow side of things. David Lynch’s unique cinematic approach combined with Mark Frost’s knowledge of storytelling and television made for an interactive auteur whodunnit that generated a strong bond between viewers and the series, as well as among viewers themselves. To decrypt the show was a puzzle given to the nation at large, sparking much discussion among viewers. To my mind, that was a first in auteur television. I should also note the importance of the series airing on a major American network (ABC), allowing it to reach a large public and setting it up for future distribution abroad.

The relationship between “auteurist” television with the Twin Peaks series surely was made nowhere more explicit than when the film Fire Walk With Me was released. I’d be fascinated to hear your thoughts about the nature of this transition in terms of exhibition and the effect it had on audiences…

Fire Walk With Me was done without Frost. It was pure Lynch, perhaps his most experimental film to this day (lest we forget the catastrophic reception it received from audiences and critics alike when it was first released). The film retained all the auteurist potential of the series while leaving its most accessible elements behind. This was a shock for many people who were not ready for the darker avant garde tone of FWWM. The cyclical and rather peaceful nature of the series was abruptly shattered when Twin Peaks was transposed to the big screen. The film also had to get to the heart of the matter in a little over two hours in contrast to the temporality of the series, and the surrealist moments that could be distilled here and there within the narration of the series were much more concentrated within the film. This is both the strength and weakness of FWWM, which is a masterpiece in my opinion, but one that had to do away with much of what gave the series its quirky charm.

Did this shift between the TV series and the film FWWM also influence the way its broader (addictive!) mythology was represented?

The film focuses strongly on the influence of the Lodge entities, which makes perfect sense in the context of a prequel because they set everything in motion. Their quest for Garmonbozia is similar to Hindu mythology’s soma food that allows deities to remain immortal. It is their desire for this food that leads to the murder of Laura Palmer; they are the puppeteers who manipulate everything in Twin Peaks, a “northern-passage” (the original title of the series) towards their realm. This mythology will likely engage with Hollow Earth theories in the third season if Mark Frost’s latest book, The Secret History of Twin Peaks, is any indication.

This increased focus on the murderous actions of the lodge entities in the film led to a more horrific tone while the soap-opera elements of the series were tuned down. Fire Walk With Me definitely gave Lynch the possibility to be more experimental visually speaking, making more connections to paintings (one needs to remember that he is originally a painter himself) and his favorite films (especially Hans Richter’s Dreams That Money Can Buy). Suddenly, the works of Max Ernst, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Jean Cocteau and others were exposed, though slightly filtered through Lynch’s own approach, in a mainstream movie linked to a popular television series. This was the perfect recipe for the implosion that FWWM created upon its initial release! The fact that a TV show was able to produce such a puzzling work of art, an incredibly rich and dense film on so many levels, is an amazing tribute to what Lynch and Frost initially created.

From the cast of many familiar faces to a number of key personnel behind the camera, Twin Peaks of course continues Lynch’s collaborations with a number of individuals he had worked with in his films. For you, what are the most important ways that Twin Peaks connects to Lynch’s previous feature filmmaking projects?

There is a strong sense of continuity in Lynch’s films thanks to the recurrence of certain actors. One can say that this helps create a “Lynchverse” of sorts, which transcends the distinct narratives, whether they are filmed for television or for the big screen, in order to create a flow that carries us along the years. In Twin Peaks, for instance, we recognize many people who had already appeared in various projects of his — Jack Nance from Eraserhead, Kyle Maclachlan from Dune and Blue Velvet, Catherine Coulson from The Amputee, etc.

Lynch seems to appreciate creating a trustworthy family around himself, one that is radically different from the generally negative vision he has of the family unit in his movies, particularly in Twin Peaks where it is a source of trauma and perversion. It seems to me that he is able to generate this continuity with his cast because he does not really hire actors, but rather people. Contrary to what is usually done in the movie business, he does not ask them to read a part for him when he is looking for someone to play a role, he has an informal discussion with them. He gets to truly know them, the people behind the masks. In a sense, he does not really ask them to perform for the camera, but to be themselves. This is why, in my opinion, they sound so real and also why he is able to use them from film to film.

Twin Peaks is also strongly connected to the rest of his filmography from a thematic and symbolic point of view. In my book, for instance, I suggest that the famous Red Room, an antechamber to the White and Black Lodges, might be understood as a psychoanalytical and alchemical secret garden, what Carl Jung calls a “temenos” — a place where people can explore their unconscious so as to progress towards individuation. The presence of birds, water (the chevron wave motifs on the floor), statues, etc. seem to indicate that this might be such a place. What is interesting is the fact that this motif can also be easily found in several other films by Lynch. Arrakis, for example, the desert planet in Dune, is a garden to be and Paul’s quest will consist in turning the arid wasteland (which could also be understood as his own unconscious) into a lush garden. Blue Velvet starts and ends in a garden — it’s about a fall from Eden (the father’s) and about what ensues in order to gain back mastery of this oedipal paradise.

Of course, gardens are only one such thematic link to the rest of his filmography, one can find many others. These links are not only aesthetic, but also relate to his own personal beliefs. Lynch has made it clear to the world during the past ten years or so that he is a strong follower of the Transcendental Meditation teachings of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. It does not really matter if we share or not his belief in TM. What matters is the fact that Lynch’s creative process is influenced by TM (as he acknowledges in his book Catching the Big Fish) and as a critic or scholar, one needs to address this when analyzing his films. In my opinion, there are clear links between TM and Twin Peaks, but also between TM and the rest of his films. The series and film are part of a continuum of references, both aesthetic and spiritual, hidden under the surface of the narrative that connect his universe into a greater whole, which also includes his paintings and his music.

Franck Boulègue’s Twin Peaks: Unwrapping the Plastic (2017) is available from Intellect. A companion blog, Unwrapping the Plastic, can be found here.