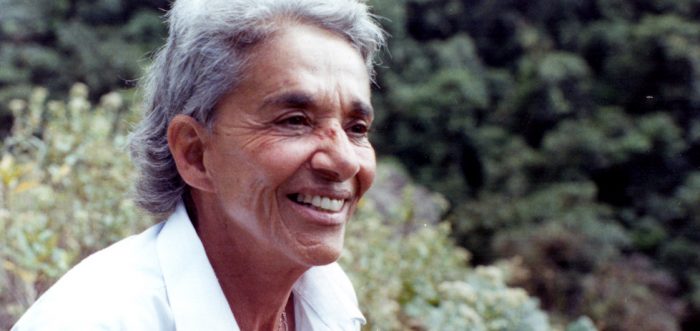

“Silences in my songs come from emotions that make me mute.” So said the singer Chavela Vargas, a complex trailblazer in the world of Mexican music who passed away in 2012. With their documentary Chavela, filmmakers Catherine Gund and Daresha Kyi give voice to these emotions, turning her story into an engrossing portrait of not just the artist herself, but the culture out of which she arose. Despite adhering to a conventional documentary framework, Gund and Kyi’s selection of interviewees signals an admirable refusal to descend into straight hagiography.

Like most biographical documentaries, after some brief exposition we start at the very start. Born in Costa Rica, Vargas left for Mexico City and gained recognition for singing rancheras – passionate songs that were traditionally the domain of men. She became iconic in part because when she burst onto the cabaret scene she “wasn’t just a little fountain,” as one of the talking heads here puts it. Instead, she “sang like a man”, wearing pants and drinking heavily. As the singer Eugenia León says, she “got rid of all the embellishments” in rancheras, turning it “into the music of the soul.”

In an intriguing conceit that they make good use of, the filmmakers intercut stock standard archival footage and talking heads with a previously recorded interview Gund undertook with Chavela in the 1990s. The distance between the time of these interviews allows the filmmakers to flesh out the complexities of Vargas’ character, fact checking her as they go.

On the ample evidence presented here, Vargas gave her all, and then some, in her performances. It was an approach that, while cementing her status within the pantheon of Latin American music, clearly took a toll on her personal life. In particular, she spent decades as an alcoholic. Her condition was, according to Alicia Pérez Duarte (her partner at the time), “severe, very severe.” She famously drank whole towns dry of tequila, embarking on massive benders with not just fellow performers but anybody she could rustle up. The way Vargas tells it to Gund in their previously recorded interview, the drinking finally stopped when she visited some Shamans in a pilgrimage through the wilderness that cured her alcoholism.

“That’s not how it happened,” Duarte simply states immediately afterwards. She argues that Vargas sobered up only after she intervened following an incident where a drunk Vargas forcefully taught Duarte’s son how to shoot a gun. Duarte says that Vargas explained herself by arguing that she was teaching him how “not to be a faggot”.

It’s a revealing statement, an illustration that Vargas’s relationship with her sexuality was complex. The episodic nature of Chavela works to emphasise just how intense her multitudinous relationships, both sexual and platonic, were. The film chronicles everything from a fling with Frida Kahlo (“her eyebrows together were like a swallow mid flight,” Vargas marvelously notes) to her waking up in bed with Ava Gardner to a summer encounter with the writer Betty Carol Sellen. Sellen notes with a sense of resigned sensitivity that “I always knew that it wouldn’t matter to her if she saw me again.”

In the film’s final act, the director Pedro Almodóvar appears, both as a talking head and in archival footage. His late but weighted appearance reflects the key role he played in Vargas’ late career revival. Not only does he continue to use her music in his films (most recently employing “Si no te vás” in last year’s Julieta), he played an instrumental role in organising a successful run of performances across Spain and Paris when she was in her eighties, after some fifteen years in the wilderness.

Despite her trailblazing status, Gund and Kyi suggest that Vargas never came to terms with her early parental abandonment. Her deeply conservative and religious mother and father would literally hide their confounding daughter from visiting guests, treating her “like a rabid dog”. She only publicly came out very late in her life. The conservative culture that she ended up challenging exerted its grasp on the singer for decades. It’s with this central insight that Chavela becomes not just a revealing, if mostly conventional portrait of one remarkable woman, but also the culture which at various times embraced, abandoned and then embraced her again. As a cabaret owner aptly puts it at one point in the film, “Mexican society is deeply hypocritical. You can do whatever you want, as long as it’s not in the open. As long as it’s on stage.”