In 1985, Donna Haraway’s influential essay A Cyborg Manifesto made a chilly declaration: “By the late 20th century,” she wrote, “our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized, and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs. This cyborg is our ontology; it gives us our politics.” One year earlier, President Ronald Reagan had unveiled the Strategic Defence Initiative, an elaborate program to develop missile defense systems to protect the United States from nuclear attack. The mainstream media quickly nicknamed it ‘Star Wars’. Later that year, Reagan won the 1984 US Presidential Election in a landslide victory. Just 11 days before the election, on October 26, a film called The Terminator was released in American cinemas. It was the first feature written and directed (to completion) by James Cameron, then a 30-year-old Canadian special effects designer and Roger Corman alumnus.1

Cameron claims that his original concept for the Terminator came to him when he was suffering from a fever and had a dream in which he visualised “a chrome torso emerging, phoenix like, from an explosion and dragging itself across the floor with kitchen knives.”2 When he woke up, he immediately began sketching the figure on hotel stationery. Inspired by various science fiction sources, most significantly the writings of Harlan Ellison and his work on the television show The Outer Limits (1963-65) as well as upscale B-movie action films The Driver (1978) and Max Max 2 / The Road Warrior (1981), Cameron’s story of a cyborg assassin who is sent back in time from the year 2029 blended high-concept genre filmmaking with comic book violence and a pulpy, low-budget urgency.3 While it operates with different goals, Cameron’s project shares many of the same cultural concerns as Haraway’s, setting the tone for her manifesto.

The Terminator was a significant financial success (both for Orion Pictures in America and globally) and made a superstar of former bodybuilding champion Arnold Schwarzenegger. Cameron capitalised on his breakthrough with his next two films — Aliens (1986) and The Abyss (1989) — but he would begin the new decade with what is arguably the most interesting film of his career: Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991). Originally exhibited in both 35mm and 70mm film formats, T2 recently underwent a digital 4K restoration and 3D conversion and was re-released in cinemas globally in 2017, more than 25 years on. This contemporary presentation adds an extra ripple to Cameron’s existing analogue-digital hybrid: a high-tech artefact from the celluloid age, reproduced by an even more advanced machine for 21st-century consumption.

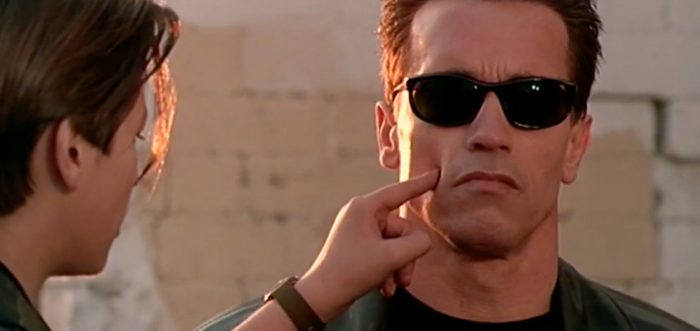

Set in Los Angeles a decade after the events of the first film, the story follows 10-year-old John Connor (Edward Furlong, in his first acting role), the future leader of the human resistance in a war against Skynet, an artificial intelligence system instrumental in engineering the apocalypse. His mother, Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton), has been locked up in a mental institution for her belief in this post-apocalyptic future, which she predicts begins with a nuclear holocaust occurring on August 29, 1997. Skynet send an advanced Terminator back in time from the year 2029, the liquid metal T-1000 (Robert Patrick), to kill John and prevent his future actions, while the human resistance capture and reprogram a less advanced machine, the T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger), and send it back with instructions to protect him.

Terminator 2 was, at the time, the most expensive film ever made. Compared to the first film’s modest budget of $6.4 million, the sequel cost a whopping $102 million. Filmed over 171 days, it covered over 20 locations across California and New Mexico and employed over 1000 crew members. The ambitious computer-generated images were overseen by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) and took a team of 35 animators, concept artists and computer scientists ten months to produce. No longer influenced by the Roger Corman school of efficient independent filmmaking, Cameron was now operating at an unprecedented level and creating his own brand of cinematic maximalism.

I first saw Terminator 2 when I was six, staying at a family friend’s house in New York. My parents were out and their friends were in the kitchen. I remember watching it alone in the lounge room and seeing the opening sequence, which presents the future war against the machines in the year 2029. These images of a post-apocalyptic world — metal and human skulls crushed together under tanks in a barren, burnt-out wasteland — frightened me so much that I hid behind the couch. When the story entered the present day I managed to calm down and return to my place in front of the television, hypnotised. It’s the first film I remember understanding was designed for adults, and the impact it had on me was profound. When Schwarzenegger’s T-800 — the film’s surrogate father figure — sacrifices itself at the end and is lowered into molten steel, it had a primal emotional effect on me (and still does).4 When it finished, I immediately rewound the VHS and watched it for a second time. In writing this piece I have realised that, in one way or another, I have been thinking about this film for 20 years.

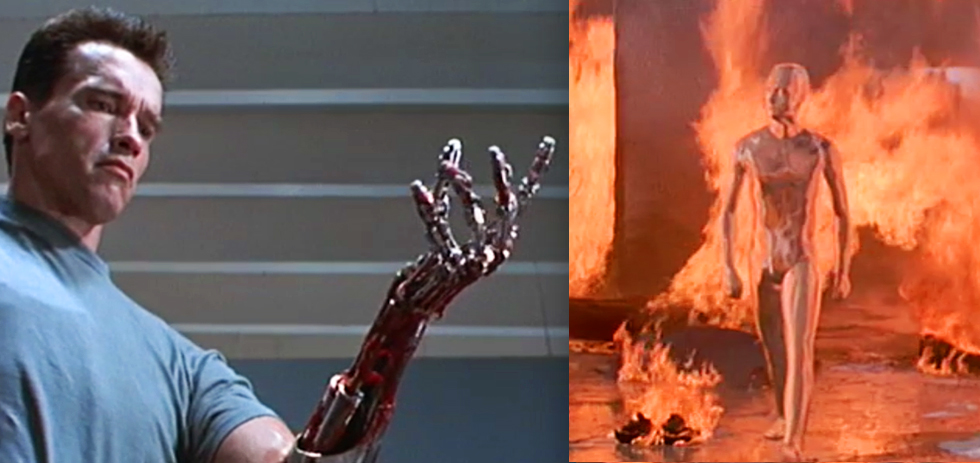

Revisiting the film now, I am struck by the curious tensions that exist between the analogue and digital elements, in both its formal construction and the narrative itself. While made in an analogue era, the film presented groundbreaking CGI technology for its time. The effects were the combined work of the Stan Winston Studio, who designed the practical puppets, prosthetic make-up and models, and ILM, who created the digital effects. These two aspects of production were both working at extremely advanced technical levels and it is this collision that gives the film its singular energy. T2 lies at a unique transition point, strongly invested in both its analogue forms and digital innovations.5 While ILM had made significant developments in CGI while creating the morphing underwater alien in Cameron’s The Abyss, T2 is arguably the moment digital effects went supernova, at least in the public eye.

As a cultural product of the early ’90s, it is easy to be drawn to the analogue artefacts of T2: video arcades, cassette players, monochrome computer monitors and payphones are littered throughout. The environments they exist in feel similarly tactile. Unusually for a studio film of its time, T2 was entirely shot on location, with no sound stages used at all. The opening shot — of a Los Angeles highway traffic shimmering in the sun — sets the tone; from that point on we experience the city as a series of urban non-places: underpasses, shopping malls, alleyways, hospital corridors, stormwater drains, gas stations, corporate buildings and factories (with a brief excursion into the Mexican desert). These landscapes are cold, threatening and strewn with detritus. Beautifully lit, they possess an almost uncanny quality; grounded in reality and yet completely cinematic. These real worlds establish a strong foundation for the science fiction spectacle to play out, as two machines seek to destroy each other in the LA wastelands.

Indeed, much of the film feels real. This has a lot to do with the fact that the bulk of it is in fact live action, unaugmented by special effects. Even though it is still perceived as a special effects-driven film and considering the amount of time it took to develop them, the actual screen time of the CGI is just five minutes. There are only 42 CGI shots in the film (as a comparison, Avatar had around 2800 and even Mad Max: Fury Road, a film praised for its practical stunts, had 2000) and these are almost solely devoted to the visualisation of the T-1000. The rest of the stunts, crashes and explosions have a visceral effect. A tow truck did actually drive into the ground during the stormwater drain chase, Schwarzenegger was on top of the tanker as it slid into the steel mill and they did blow up the four-storey office building that doubled as the Cyberdyne headquarters.

As opposed to many contemporary blockbusters, these action sequences do not feel like they have been edited in a blender. They have a dynamic, striking quality; the elaborate clash of materials creates a powerful kinetic experience. Sarah Connor’s apocalyptic dream sequence was created by building a model of downtown Los Angeles which was then destroyed. The tangible images of the atomic blast: cars being blown off the road, palm trees on fire and ashen bodies blown apart help lend the scene a vivid, hallucinatory tone. When the T-800, wanting to prove to Miles Dyson that it is a machine, cuts open its own arm and reveals the metal endoskeleton underneath, the practical design remains as vividly lifelike and difficult to stomach as it was in 1991. In comparison, much of the CGI feels dated.

The cyborg concerns of the story — those of organisms that are part human, part machine — mirror this clash of analogue and digital technologies. This dichotomy is also present in the narrative, as represented by the two terminators: Schwarzenegger’s heroic, mechanical T-800 (analogue) and its advanced prototype, Robert Patrick’s villainous, liquid metal T-1000 (digital).6 The T-800 is a robotic endoskeleton disguised by living human tissue and, in its initial role as the villain in The Terminator, is emblematic of what Susan Jeffords describes as a Reagan-era model: the Hard Body, a foundation of the hyper-masculine 1980s action movies of Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone.7 In Terminator 2, Schwarzenegger, as the protector of John Connor, is a warm, paternal figure. In her critical study of James Cameron, Alexandra Keller argues this role reflects the film’s position in the political culture of the United States at the time, moving from the Reagan Administration (1981-89) to the Bush Sr Administration (1989-93):

“[Cameron] may be symptomatic of some crucial shifts in American masculinity from the ethos, ideology, and policies of Reagan to those of Bush 1, who famously spoke of wanting a “kinder, gentler” nation and, implicitly, national character.”8

The analogue T-800 is an exemplary father figure to John: solid, dependable and receptive. In contrast, the T-1000 is completely untrustworthy: made of ‘mimetic poly-alloy’ (liquid metal), it is able to mimic the appearance of anything it touches. Cunning and amorphous, it is a digital disruptor. In a making-of documentary, Cameron described the contrast between the two terminators in vehicle terms: “If the 800 series is a kind of human Panzer tank, then the 1000 series had to be a Porsche.” As the less advanced of the two models, T-800 is the underdog. The image of its battered body at the end is rousing: arm torn off and wires hanging out as it drags itself heroically along the ground. The audience is placed to cheer on the analogue force as it ultimately destroys the digital.

Taking into account the financial success of the Titanic 3D rerelease, which grossed $343 million dollars worldwide in 2012, it is easy to look cynically at the current rerelease of Terminator 2: 3D as a pure money-spinner. It is unclear whether the idea initially came from the studio or James Cameron himself. In the press release, Cameron diplomatically stated that “it would be fun to see it and fun to get it back into cinemas 25 years later, because you’ve got a whole audience that only knows the film from video, DVD and Blu-ray”. The conversion process was managed by Lightstorm, Cameron’s production company and involved scanning the original 35mm negative and restoring it in 4K, which was then converted into 3D. This took around a year to complete, with Cameron reviewing the changes as they were made and personally supervising the final colour grade.

Cameron has said he often shoots with shorter lenses and is very concerned with distance within the frame. While it was not composed with 3D in mind, he apparently found T2 relatively easy to convert to the format as there were a lot of depth cues. The 3D seen in the T2 rerelease doesn’t jump out of the screen and is more concerned with creating a greater sense of depth and space within the frame. The natural texture and definition of Adam Greenberg’s original 35mm cinematography provides some nice moments in the conversion early on, but after a while it is easy to forget that the 3D is even there. It is an inoffensive addition, suggesting that the rerelease should primarily be seen as an excuse to see the film in a theatre. Which leaves one to wonder, why bother in the first place? Cameron has said in 1991 that he considered the 70mm release of T2 to be the “gold standard” of cinema experience, but now believes the 4K conversion is the best the film has ever looked. Well known as a technical innovator (his work in creating underwater cameras for The Abyss alone resulted a series of patents), one could see Cameron treating the T2 3D conversion as a kind of large-scale personal project. However, these material concerns of digitising the existing artefact have resulted in a conversion that is curiously undistinguished. In the trailer for the 3D rerelease, Cameron speaks about how “the images feel more real in 3D” and that “there is a lucidity to it, you really feel like you’re there”, ignoring the fact that it is the practical construction and analogue spirit of the original film that give it this sense of realism. Cameron has said that if he were to make T2 now, much more of it would be done digitally, and it is this characteristic compulsion to explore state-of-the-art technology that has ultimately proved to be detrimental to his craft.

T2 ends with the camera moving along a highway at night as Sarah Connor reflects in voiceover:

“The unknown future rolls toward us, I face it for the first time with a sense of hope, because if a machine, a terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can too”.

T2 changed the course of how large-scale Hollywood films are made and what was expected from them visually. This special effects-driven blockbuster mentality eventually led, 18 years later, to James Cameron’s Avatar (2009). That film’s 3D release in December 2009 prompted many cinemas to invest in digital projection systems and is considered a turning point in the winding back of traditional celluloid projection. The kind of science fiction digital dreamings found in Cameron’s analogue-era films had now become a reality. Ironically, in ushering in this new digital age, T2 ended up unleashing a monster that would seek to destroy itself.

The digital conversion process that has redelivered T2 to cinemas contributes nothing of value to what was already great about the film. In the current era of digital cinema dominance, it is easy to look at the death of analogue processes as being inevitable. But with many recent large-scale productions being shot on celluloid, as well a gradual increase in analogue and practical effects, it might be possible to face the future with a sense of hope. Maybe both these analogue and digital approaches, unlike their android characterisations in the film, don’t have to work in opposition.

In an age where drone strikes and artificial intelligence are now a reality, Haraway’s manifesto on the politics of a cyborg world is now more relevant than ever. T2’s 1991 vision of a post apocalyptic future where Skynet runs the scorched earth remains unsettling, though the film’s hopeful ending can be viewed in 2017 as a work of warm, comforting nostalgia. Rewatching the film in an era of blockbusters overrun by photoreal yet lifeless computer-generated imagery, it is clear that T2’s analogue approach, with its consummate human craftsmanship, is an intrinsic part of its enduring reputation.