Senator. How are you going to counter Mr. Humphrey in his, uh, backgrounding you as far as the delegate votes go?

Senator Kennedy has been… Senator Kennedy has been shot! Is that possible? Is that possible? It could… Is it possible, ladies and gentlemen? It is possible he has… not only Senator Kennedy… Oh my God! Senator Kennedy has been shot.”

This is a transcription of a reel-to-reel tape recorded by radio reporter Andrew West on June 5th, 1968 — the night of the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles, California. It was transcribed by poet Kenneth Goldsmith and published in his 2013 book Seven American Deaths and Disasters.

In the above excerpt, Goldsmith’s transcription omits a crucial detail — the question of delegates precedes the shock of the gunshot by roughly half an hour. Here, as elsewhere in his book, the flattening of time and removal of any sounds other than speech adds to the sense of the uncanny: this written text, once spoken by eyewitnesses, reporters or news anchors, is all at once intimate and impersonal. These disasters — from the two Kennedy assassinations to the Columbine shooting — happened as people watched on. The act of recording turns history into media event and the eventual transcription of media output both preserves and sanitises recollection: the pain and panic of others contained in a small white paperback on my shelf.

Beyond sound and image, what Goldsmith also removes is context. Our memories of these events — or our understanding of them — are already mediated by film and television, and in the case of the book’s final chapter, on the death of Michael Jackson, the internet. These malleable transcriptions build on our knowledge of events but never challenge them. The near-verbatim eyewitness accounts of the Kennedy shooting give us an expected sense of panic and dislocation, but can’t adequately reflect on the fact that his death was arguably the first major act of retributive violence in the conflict between Palestine and Israel to take place on American soil.

Memory Jackets, a screening of three short films at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art, tethers historical dislocation to violence. Though the series, curated by Queensland Film Festival programmer John Edmond, was not planned to closely coincide with the 70th anniversary of Al Nakba (the mass 1948 expulsion of Palestinians from their land), the films selected gain new resonance in light of the horrific acts of violence perpetrated in Gaza this past week.

All three films are, on the surface, concerned with surveillance, and challenge the primacy of the image in documenting history. They provoke through acts of withdrawal — the first film lacks any soundtrack, the second any context, and the third any moving images. The elisions stunt any simple search for ‘truth’.

Hold him! Hold him! Hold him! We don’t want another Oswald!”

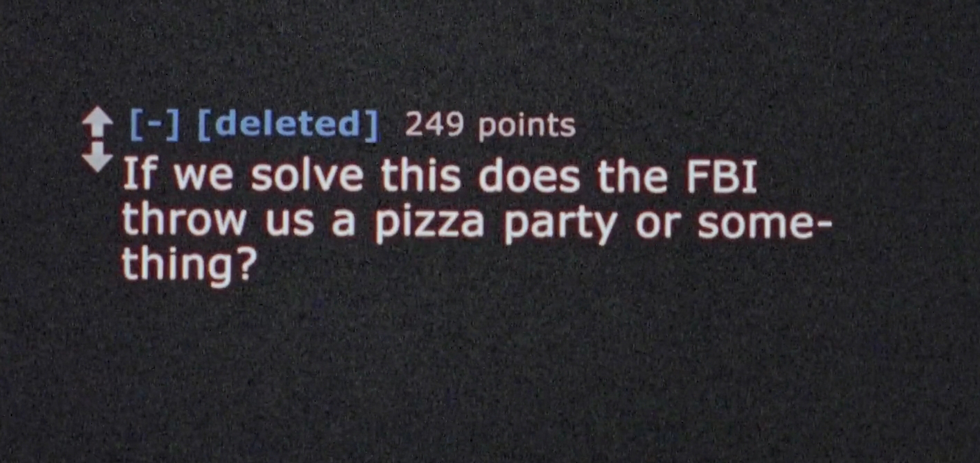

Chris Kennedy’s Watching The Detectives is like one of Goldsmith’s chapters written in static images. The event it depicts is the Boston marathon attack from 2013. Instead of an eyewitness account, we’re shown screenshots from Reddit. Users like ‘prostate_massage’ analyse crowd photos released by law enforcement and bystanders; for once, the FBI shirts they kept in a dusty drawer took on the official acronym. Men are targeted for their skin (“2:BROWN” is an early note on one photo), backpacks (intense debate about the potential sag of a rice cooker) and their supposedly inexplicable reasons for standing around for too long at a major sporting event. The fixation on identity is a pattern: ‘anons’ get credit for spying something pseudonymous users hadn’t and their suspects are identified by the colour of the shirts — that is, until the viral Reddit thread lands photos of two of the young men uninvolved with the attack on the front page of the New York Post.

The screenshots have been cleaned up and transferred to film, giving off the feel of old classroom slides and making a reasonably recent internet event seem decades old. The effect of links to the parent post and permalink anchored under almost every comment is much the same. We’re continually reminded that this thread, despite the shitposting, is history. But like all histories, it bends to the whims of who tells it. Kennedy accelerates through a deluge of theories, ‘evidence’, and refutation like it’s snappy dialogue. The calls for calm and rational thinking — few and far between — play out like speed bumps. The tempo encourages us to get invested in seeing what we know to be wrongheaded, defamatory claims through to their end; I had completely forgotten about the missing Brown student who was momentarily internet suspect number one, and the act of remembering it brought on a very strange sense of nostalgia: while wholly dislocated from disasters like these, we’re able to follow every morsel of information online. We remember not the horror, but the experience of perverse fascination.

You heard a balloon go off and a shot. You didn’t really realize that the shot was a shot. And yet a scream went up.”

The second film in the series is more of a direct provocation. Unlike Kennedy’s film, in which we parse the reactions of others, Johann Lurf’s Twelve Explosions rests entirely on our ability to figure out what’s wrong with his series of vignettes. It operates like a structural film, cutting between shots of small fireworks explosions in the Vienna streets on the cue of sound, rather than image. Across six minutes, we’re exposed to distinctly different patterns of cutting: at first the image and sound seem perfectly synced, to the extent that I thought the first shot contained no hint of an explosion at all. The next one has a delay of about a fifth of a second, allowing me to see a connection more clearly, but in turn prompting doubt about my remembrance of the explosion thirty seconds earlier.

Shot in what must have been the early hours of the morning, Twelve Explosions gives off the air of an evacuated urban centre, or a facsimile city built for military testing. Few cars pass by throughout and as we move closer and closer to the heart of the city, the wide, vacant streets — at a late point seen from above — reinforce the disconnect between these incidents and the surveillance footage that emerges from small-scale bombing attacks in the West. In Lurf’s film, there is no panic, no response, no acknowledgement of any of these ‘explosions’ by anyone. The human element in their construction — one of the primary fixations in Kennedy’s film — is likewise absent. We can’t track any clear pattern as the explosions rage on, revealing a mechanical randomness that gives way to absurd humour.

He still has the gun. The gun is pointed at me right at this moment. I hope that they can get the gun out of his hand.”

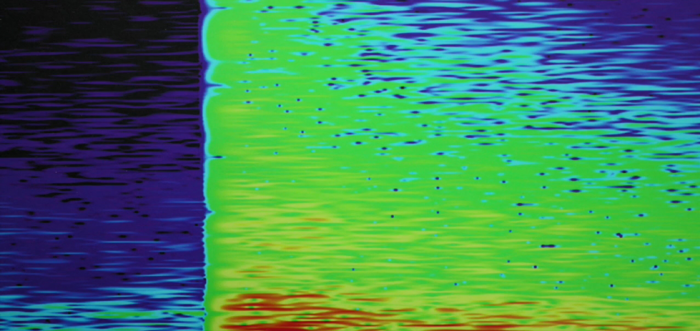

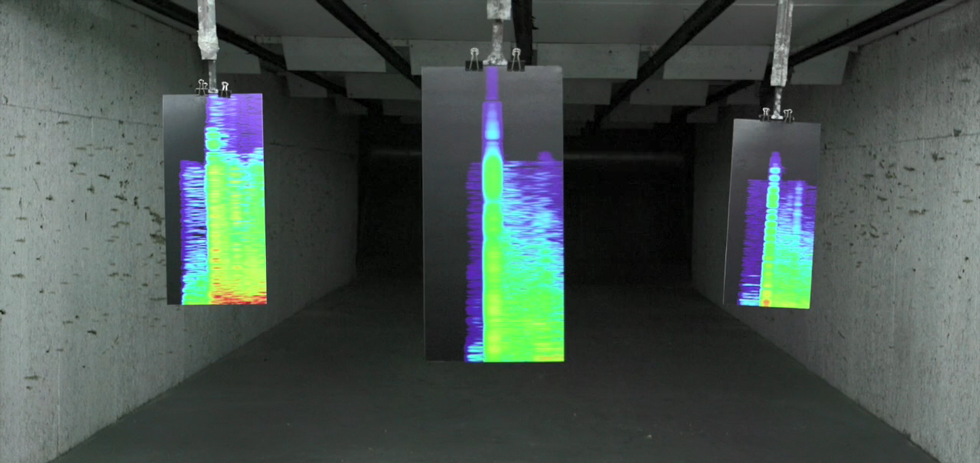

After the literal spark of Lurf’s short, the final film in the series is a sobering reminder of the impact of violence on communities and the way in which sound, over image, can present previously unconsidered evidence. Rubber Coated Steel emerged from the intersection of activist journalism and legal evidence. The Turner Prize-nominated organisation Forensic Architecture was commissioned by Defence for Children International Palestine to assist in the investigation of the murder of two unarmed Palestinian teenagers on Nabka Day in 2014. Forensic Architecture provides “advanced architectural and media research” to legal teams looking to prosecute human rights abuses; many of their projects involve using 3D rendering software to recreate zones of conflict. In this particular case, the artist and forensic audio expert Lawrence Abu Hamdan worked to distinguish between sounds of rubber bullets and live ammunition fired from the guns of Israeli soldiers.

Forensic Architecture provided a three-minute video report to DCI Palestine in late 2014 and published a more extensive account of the incident on their website in 2016. Hamdan’s short film, from that same year, is an artistic account of his very real evidence. We are informed at the start of the film that we will witness a reinterpretation of a fictional court case, in which Hamdan’s audio evidence is presented to an Israeli tribunal. What that amounts to is silence: in the setting of an underground shooting range, we read a transcript of the ‘trial’ at the bottom of the screen, and relevant images and sound excerpts (the latter presented in graph form), move towards the camera on target holders. The bounds of the fictitious trial are elastic: much as the defence attorney decries irrelevant evidence and hearsay, the picture presented by Hamdan is damning not just for the border guard (who was indicted on manslaughter changes but last month took a plea bargain) but for the Israeli military at large. The charge that the in-film Hamdan seeks for the border guard is murder, and the intention of the guard to kill seems fairly well established. Though definitely affecting, the short is most effective as a muddying of the waters around journalism and art. It adopts the restrained, text-heavy approach of certain Field of Vision shorts, converting the facts of a case into a wide-reaching metaphor for the underground and closed-off nature of justice under authoritarian rule.

One man has blood on himself. We’re walking down the corridors here. Repetition in my speech. I have no alternative. The shock is is so great. My mouth is dry.”

It is a jarring sense of specific contemporaneity that gives this series of films an unexpected resonance. Also jarring is the reminder that no regular screening series of this calibre exists here in Sydney.1 Memory Jackets is the fourth IMA screening this year presented by Queensland Film Festival, a reflection on the commitment of both institutions to the screening of boundary pushing cinema — particularly contemporary film — outside of a festival setting. May there be many more.