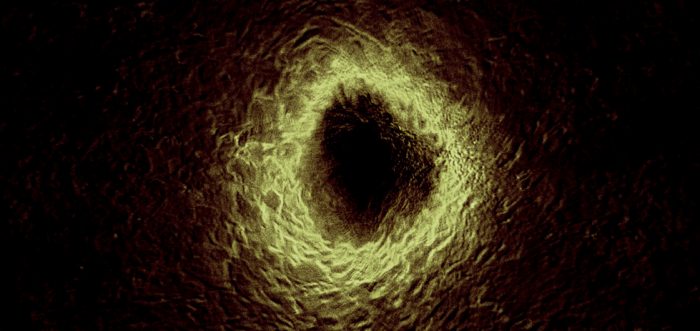

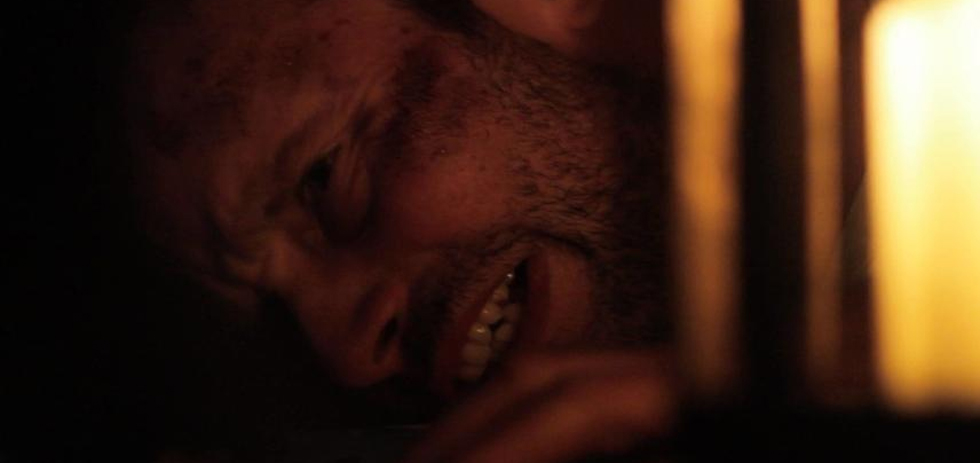

Scott Barley’s films are hard to see. Not in terms of accessibility — many of films are available to stream on Vimeo or as free downloadable DCPs on his website — but literally; his films are bathed in so much darkness that it’s sometimes hard to define exactly what’s on screen. When the screen does light up, it’s often frightening – violent strobes and raging fires that shatter the earthy calm before them. In between those extremes come gorgeous portraits of the natural world: forests and waterfalls, the occasional lone animal in the moonlight. It’s only when humanity intrudes on these scenes that Barley’s films approach something like ugliness, and, even then, the compositions are made with such care for aesthetics that it can be surprising to learn that all of his films are shot on an iPhone.

Barley’s feature film Sleep Has Her House feels like a culmination of his aesthetic and thematic interests, resulting in a haunting cinematic experience that would be meditative if it didn’t feel so post-apocalyptic. In anticipation of the Environmental Film Festival Australia’s screening of Sleep Has Her House at ACMI on October 13th, I reached out to Barley over email, and we discussed filming on an iPhone, the spectral qualities of cinema, and Death Grips.

You shoot your films primarily on an iPhone, which sometimes gives a painterly aspect to your images; you utilise digital blur in a way I find quite astounding. From this base, you often merge multiple shots together to create collages of motion and stillness. I know you don’t like to discuss the exact process behind this, but I wanted to know what drew you to the phone as a tool in the first place? Especially since, having been to film school, I imagine you’ve had access to more professional equipment?

It was in fact because of film school that I decided to move to shooting on iPhone. In my last year of my undergraduate studies, we had the opportunity to use an ARRI Alexa, with which I made Shadows, a short film about my grandmother Doris’ deterioration and social immobility in old age.

I suppose it was my first film where I was really trying to paint with the light and create a world through sound. I used the 6 channels of audio to play throughout the film as if they were separate rooms of her house. These ambitions were there in my previous short films, but not as pronounced or as well-crafted. We re-enacted scenes that had recently happened to my grandmother, such as her suddenly losing ability to move her legs while in the bath and becoming trapped there for nine hours. The whole ordeal made me feel guilty, like I had been a bad grandson, like I hadn’t been there for my grandmother as much as I should have been whilst studying. She was lonely and was getting frailer. We decided together to make a film re-enacting the event, to hopefully bring us closer, and provide a sense of closure and catharsis to the ordeal. Through re-enacting, through creating, it would help us forget and build new memories together as grandmother and grandson.

As I say, the ARRI Alexa was a terrific camera, but each shot took a long time to set up. All the equipment was big and very heavy and made the set cramped; all the lights made it very hot; and progress was slow. I also couldn’t shake the feeling that we were trying to convey this vulnerability – this authenticity – and here we were with £200,000 worth of equipment in my grandmother’s own home which was worth not much more than half of that. It felt wrong. I wanted to take what I had learnt – visually, sonically and humanly – from that experience and apply it to something where I could harness the immediacy and lightness that only a smaller device can deliver. I also believe that the best camera is the one that is always with you; in this case, my iPhone.

Do you ever feel a dissonance between the rather populist tool of your choice and your subject matter, which often presents a world without people at all?

I don’t think the populism of the camera I choose to use matters. I use my iPhone because it’s light, and freeing and enabling for the way I wish to work; it is also the camera I always have on me. Somebody else may always carry a DSLR around their neck, or even something bigger. And of course, it doesn’t have to be an iPhone, it could be any phone with a camera. Now, I always begin a film almost like one would keep a diary. I have no idea, or agenda to make a film. I simply document. I shoot what attracts me: random things, animals, variances in light, the water, the stars; simply what draws me in on different days, different nights, in different places, both using video and still photography on my phone. Once I have built up a body of footage, I start to see connections. These pieces of footage could be taken months or even years apart – and miles apart too. Once these connections are established, a narrative – through images – begins to germinate.

In a sense, I think that my filmmaking is an ongoing journey of failed attempts to get as close as I can to [a] sense of tactility within a digital medium. I studied fine art before studying film, and that’s really where my filmmaking process began. My first love was painting. I was very inspired by Frank Auerbach, and how he was essentially creating sculptures out of paint, due to the incredibly thick relief and texture of his applications. To me, his paintings are like a moment, or motion captured in time in a much more corporeal sense than a photograph, which are more like an interruption of time, with a few exceptions, such as Antoine D’Agata’s work. In 2011, I began sculpting with paint, often with my hands, and combining earth, stone, ash, spider’s silk and insects into my pieces. From there, I combined that with video installation. I love the tactility of working with paint and other materials in this way. It brings me a sense of wellbeing and peace. [Film] is a different language – a new language – and I’m always learning; learning through making. Each time, I try to get a little closer [to that tactility].

As a filmmaker who generally avoids traditional narrative – I think one of your early works, Ille Lacrimas, is the closest to your films having what could be described as a plot – you are often categorised as an experimental filmmaker, sometimes more specifically within Re-modernism. Do you find such genre labels confining or reductive?

I find compartmentalised terms very reductive. At best, they’re simply redundant to me. I have my inspirations, of course: Nathaniel Dorsky, Phil Solomon, Michelangelo Antonioni, Robert Bresson, Maya Deren, Jean-Claude Rousseau, Béla Tarr, among others, and their work is profound to me. But I find myself inspired more by music for my films: Grouper, Ligeti, Scott Walker, Swans, and Death Grips.

I find Death Grips an inspiration for several reasons, particularly in their career up to and including the release of the first half of their double album, The Powers That B. Up to that point, I believe describing them simply as a band would undermine their scope and intent. I see them as a multimedia art installation, a continuous art project comprised of three people that embraces the autodidactic; that celebrates and utilises an anarchism on thought, intent, creativity – and how that is communicated and shared. They seem to be almost entirely driven by their own impulses. In other words, they are completely doing their own thing. For the most part, they are not concerning themselves with what people like or want them to do, similar to Throbbing Gristle before them.

I suppose that what I am trying to do with my work – the democratisation of distribution and shooting on a phone – isn’t that unlike what [Death Grips] are doing with releasing and making of their music and music videos, particularly up until 2014. There is a mysticism embedded in their process, i.e. releasing music in alignment with rare lunar activity. I try to invite a mysticism, a oneness with otherness in my own filmmaking process. There is a lot of mystery to them as a group, and many deep, obscure oscillatory allusions (perhaps illusions in some cases) between their music and other culture. Their work follows a logic of sensation; we feel the viscera first, and we intellectualise it later. No matter how visceral the music is, though, there is a deep, well-thought, cerebral and poetic underpinning to what they are doing.

Many of your films feel post-humanistic. Your work often presents a world without the touch of humanity, a place of primordial nature. Sleep Has Her House especially feels, at times, like it takes place after the human race has disappeared. And I often find that your works which delete the human presence entirely – like The Green Ray, Closer, The Ethereal Melancholy of Seeing Horses in the Cold, and Evenfall – are much more calming pieces than ones that show humans. Womb, Hunter, Nightwalk, in particular, make the human form feel positively sinister. Do you find the struggle between nature and human progress to be a point of intention in your process?

I think my films are about that struggle, in some sense, because I believe we, as human beings make it a struggle. The human race is hell-bent on superseding nature itself, which is laughable when you think about how inane and ridiculous a folly that is, but the results of this folly are profoundly devastating. I don’t make political films, but in some sense my work is concerned with the anthropocene; humanity is yet to truly realise that we are nature in an active sense, and our attacks on nature will lead to a horrendous end. It won’t even be a pyrrhic outcome. The devastation caused if we continue the way we are going will be beyond all language and current imagination. In part, I want humanity to lose its ego by conveying how vulnerable it is in the face of the elements, but my films are more about the mirroring, oscillatory qualities of the phenomenological and cosmological than anything else.

Speaking of malevolent forces, light is sometimes shown as such in your work. Violent strobe lights often punctuate your films, throwing the previous calm imagery into flux. The fire at the end of Sleep Has Her House upsets that balance of nature presented before it. Save perhaps for Shadows, darkness is an often purifying force in your filmography. As a filmmaker who is a constant student of the interplay between light and darkness, do you find yourself rooting for one over the other?

Light and darkness are inextricable. I am drawn to darkness for many reasons. Darkness has always been a prerequisite to truly enter the world on the screen, and its importance in granting experiential resonance cannot be overstated. In the auditorium, the lights go down. We wait in a darkened room for a world of light to open up to us, and while our body may remain in our seat, the incorporeal essence in all of us wades toward the flickering light, haunting it as it haunts us. Our souls invest, they search in curiosity and hunger in the images and sounds. To enter a film’s world is a very spectral thing.

With so much of cinema’s power coming from its unique distinction as a bastardization of two arts—image and sound— the creation of vivid audio-visual scenarios often doesn’t leave enough room for the spectator to dream, to imagine, to question. Darkness and obfuscation—both visual and metaphorical—can assist in creating an environment where one’s imagination can coexist and harmonize with the film’s body, creating an utterly unique, polysemic experience for each individual.

The importance of darkness and the underexposed image also come from my desire to bring a tactility to vision – to go beyond figuration, beyond the object, and to feel the liminality between light and darkness as its own subject, to feel the weight of what is known and what is unknown.

I want to come back to something you just said, about a lack of room for the spectator to “dream, to imagine, to question.” Do you often find contemporary cinema overwhelming? Have audiences lost the patience to give themselves to works that demand it?

I don’t believe that most spectators have lost patience; not permanently anyway. I would posit that some modern day audiences have been taught to lose patience as a consequence of what is primarily being made available to them. If all one can practically see in the theatre is a Marvel film, then eventually, for many, that’s all they will know, perhaps even all that they think they will want to know. This is a huge problem. It is an undoing of what cinema is and can be, as well as an undoing of the freedoms of both the creator and the spectator. The cinema of today has, for the most part, become a miasma of artistic regression and oppression; one of endless remakes, of a bludgeoning repetition of the same clichéd stories; and one of rampant ignorance, carelessness, and stupidity. The cinema of today is, in a sense, the nullification of all that is and can be cinema.

I know that there is more of a hunger, or at the least, a curiosity for unorthodox cinema than what is made available – or rather, made accessible – to the masses. All of my short films are available for free to stream on Vimeo, and I often receive emails from people who have little to no knowledge of experimental cinema who reacted positively to my work. I have heard from people who have said that a Harry Potter movie is their favourite film, but Hinterlands or Nightwalk really resonated with them, and it galvanised them to begin pursuing other, more unorthodox cinematic approaches both as a spectator, and in some cases, as a creator. I think it’s essential that art cinema in general does more, working with communities to introduce novices, or self-proclaiming “film-buffs” – particularly young people – to a different kind of cinema. This is not about turning art cinema into a populist phenomenon, rather it’s about engaging with our present, fighting oppression in all its guises, nourishing the freedoms of authors and spectators, and enabling a future that continues to celebrate different methods of filmmaking and art practice, as well as the diversity of people’s interests.

In an effort to go beyond the individual and the internet space of Vimeo, and do something that could potentially be community-based, I have recently started making Digital Cinema Packages (DCPs) of my short films available for anybody to download for free from my website. They can be screened at any venue that can play them, in any part of the world, and as much as one wishes to screen them, for free. My hope is that it may lead to more of an empowerment in communities over what is screened in theatres and ease access to different types of filmmaking and short films in a cinema environment. I hope some other filmmakers follow suit. It certainly isn’t about making artists poorer. If a filmmaker just shares one of their shorts this way, it could be the beginning of really opening things up. It’s early days, and I have no idea whether the experiment will be fruitful, but I think it’s something worth trying.

I’ve brought this film up multiple times already, but I want to talk about Ille Lacrimas, as for some unknown reason it feels like a key to your work. I understand it was a student film, and as such had a crew, which is unlike how you usually work. Still, beneath the rather crowded (relatively speaking) narrative, it feels very much of a piece with your later ones. Did Ille Lacrimas have more planning, compared to your later, more free flowing work? From that, do you feel like your gradual paring down to something more elemental mirrors your subjects?

Ille Lacrimas (2014) was a relatively small project, but still the most ambitious film I had worked on at the time. The shoot was short, but the days were long. The first day of shooting was mainly at the cliffs, overlooking a beach in West Wales. I left my house at 12:30am to drive to the location and pick up other crew members and equipment, and I think we started shooting around 4:30am. I don’t think I got back home until 1:30am the following day, and each working day was almost as long as that for the following two days. When I am working on set, I have infinite energy and enthusiasm. It’s that feeling that I miss now, working alone within a more casual and unplanned process. Nowadays, making a film feels like a long journey out to sea where I almost constantly feel lost and vulnerable, interspersed with fleeting moments of feeling my feet brush against something beneath. So sometimes I do miss that collaboration, but there’s a lot I don’t miss. Collaboration is a really interesting process. Things happen and develop in ways that they never would if you work alone, for better and for worse.

I think that my later films can feel more free-flowing, as you described, but that takes just as much work, if of a different sort. As I say, my filmmaking process nowadays is certainly less planned. Ideas develop much more slowly and organically, and its more so now than ever that the film truly comes together in post-production. Hinterlands, a short film I released towards the end of 2016, was around eleven months of tinkering on and off in post-production. Work on Sleep Has Her House (which also had a year and a half of post-production) really began seven years ago if I were to include the use of the drawings I superimposed into the film. It’s a much more lonesome, gradual process, but one I find incredibly rewarding, because I feel my solitude and intimacy in the making of it is palpable in the end result.

When you sent copies of your films to me, you requested that I watch them in complete darkness with headphones. These films feel naturally suited to an art gallery or a cinema, but just that note suggests that you are actively considering your work for presentation on someone’s laptop. On the one hand, I imagine watching one of your films in a public space is a much more interactive and communal experience, albeit one where complete and utter immersion is expected. For someone on their laptop, the experience becomes more personal and singular, but the pull of distraction is stronger. Are there different versions of your films, one for each exhibiting platform? Are you worried about immersion on the smaller screen?

All the films are the same, whatever platform they are being exhibited on. The immersion doesn’t worry me. I have faith that people who care to will be able to enter that world, respond to it, and hopefully find resonance, whatever method they are watching the film. The films were made to be seen on the largest screen possible with the best possible sound, but that isn’t a good enough reason for me to omit certain people from seeing the film if they wish. I try to make my work immersive, regardless of what screen you are watching the film on. Just don’t watch it on a phone. Making a film on a phone is fine in my view, of course, but watching a film on one is a really tragic, empty experience.