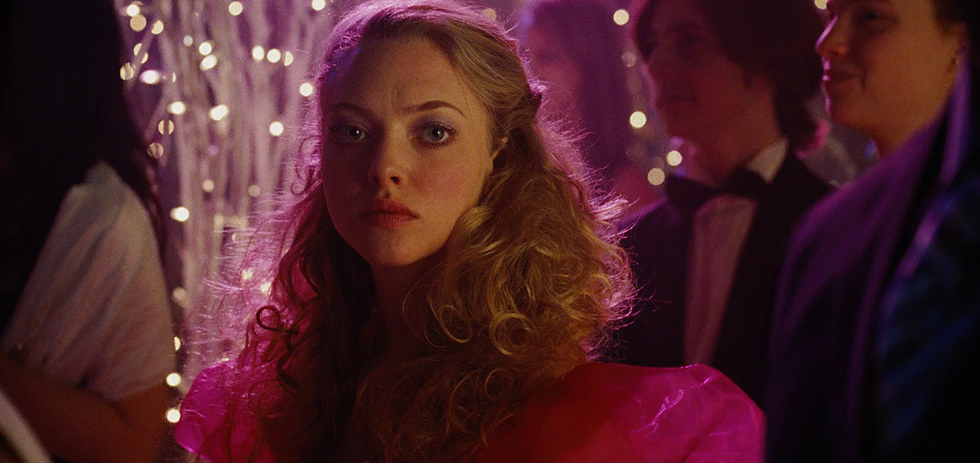

A tale of turbulent teenage friendship and demonic possession at the hands of treacherous men, director Karyn Kusama’s horror-comedy Jennifer’s Body — named for the 1994 Hole song and written by Diablo Cody (Juno, Young Adult) — stars Megan Fox as Jennifer Check, a high school cheerleader whose dark rendezvous with a careerist indie band leaves her with a carnivorous taste for teenage boy flesh, and Amanda Seyfried as her best-friend-turned-reluctant-vanquisher, Anita “Needy” Lesnicki. Finding that unusual sweet spot between hormonal horror, grotesque social satire, and genuine pathos, it’s the rare film that vividly evokes — with the help of some black magic, demonic ooze and serrated fangs — the combustible dynamic of teenage girls bound together in an environment designed to drive them apart.

But the world wasn’t quite ready for Jennifer. Released to a degree of hype in the American fall of 2009, Kusama’s film was greeted with a less-than-favourable reception from critics and audiences alike. The backlash against Cody’s Oscar win for Juno was in full swing, while Fox, careening toward overexposure in the media, was making headlines for clashing with her Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen director Michael Bay over remarks she’d made that likened him to a certain dictator. Making matters worse, Jennifer’s Body was mostly being marketed to a young, straight male demographic — negating the audience of girls it was essentially designed for — via a series of salacious, girl-on-girl trailers that promised things the film wasn’t about to deliver. Critics mostly hated it, audiences didn’t understand what they were being sold, and the film flopped at the box office.

Like a freshly undead ghoul hell-bent on righting wrongs, however, Jennifer’s Body just wouldn’t stay down. Restored to a director’s cut by Kusama for home video, the film gradually began to find an audience — especially among a generation too young to have seen it in theatres — while its depiction of a secret cabal of powerful men abusing women found resonance with the current cultural moment.

On the occasion of the film’s 10th anniversary, I spoke with Kusama about the film’s genesis, rocky reception, and unexpected redemption.

Take us back to the beginning of your involvement with this film in 2008. What was it that got you interested in Diablo Cody’s script?

Her script was so smart. It was so funny. I saw a lot of opportunity to be genuinely afraid while I was watching the movie, but I also thought it was hilarious. Reading the script, I laughed out loud — it was that kind of funny. And that idea of the secret language between girls made perfect sense to me. The script really spoke to me as a story about friendships between high school girls, and the pressures they feel to, well, ultimately destroy each other, and how difficult it is to just be a loyal good friend when you’re living in a punishing patriarchy.

At the time, Diablo was about to win an Oscar, and Megan Fox was becoming huge in the wake of Transformers. The backlash against them hadn’t yet kicked in, but did you feel like their burgeoning profiles were a pressure as you started to shoot the film?

I didn’t. I was aware of how much attention both of them got. I was aware of just a lot of film community chatter about Diablo, and what felt like a pretty gendered critique of her every move — her every word, her every dress, her every pair of shoes; it just felt like everything was so scrutinized with Diablo. With Megan, in some ways I didn’t quite see how easily she had been targeted in such a discriminatory way, because so much of the stuff when things blew up among the Transformers crew — when she became embroiled in this conflict with Michael Bay — I was surprised by how virulent and public and just how noisy the conversation was around that. So I was aware that there was a lot of talk around both of them, but I wasn’t quite aware of how it would impact the final film.

Diablo has said that she tried to write this movie as horror, but couldn’t help but find the whole situation funny.

[Kusama laughs]

You’re laughing even at its most horrible moments in this movie, like the sacrifice of Jennifer — it’s an awful scene, but it’s also very funny. It’s a very tricky thing to do. Does that all go back to your formative experience of going to see Eraserhead with you mother?

Oh sure. One of my most profound early cinema experiences was to go to our local repertory screening theatre and see David Lynch’s Eraserhead, when it was released theatrically in 1977 or 1978. My mom took me and my brother and my sister; my brother was eight and my sister was seven. For those who haven’t seen the film, it’s essentially a surrealist portrait of a man and a woman he has some kind of sexual experience with, and then she suddenly gets pregnant and gives birth to, essentially, an animal fetus of some kind, but far from human. It’s a crazy movie to see as a child. [laughs]

What’s funny is that we would see family films together at that theatre: we would go and see Creature from the Black Lagoon in 3-D, and Fantasia, you know; we would see movies for the family. This was probably the wrong choice, but it ended up being a watershed moment for me, because — first of all I saw what it did to my brother and sister; they were sobbing hysterically, and my mom asked me to take them out to the lobby, because she was actually enjoying the movie. She thought it was hilarious. And when I think about it now, of course, the movie is so much about the anxiety of pregnancy, of female sexuality, of giving birth, but primarily it’s about the anxiety of becoming a parent, and the responsibility that comes with it. In retrospect, it was one of those really funny movies to think about in Freudian terms, or something like that, imagining my mom maybe finally feeling like somebody’s gets her [laughs] — you know, overwhelmed with three kids who were basically spaced a year apart from one another. It was a really amazing experience for me, and incredibly memorable to have wanted to see the film, but also to protect my siblings — so I watched it through the portal of the lobby doors.

I think I’m only slightly exaggerating to say that Jennifer’s Body has to be one of the most mis-marketed films in the history of film marketing.

[laughs] There’s a lot riding on that mantle!

I remember when the film was being teased, and the trailers basically seemed designed to titillate — there was a lot of focus on Megan, there was a heavy promotional push on Amanda and Megan’s kiss in the film. What’s going through your mind as this was happening? You feuded a little bit with the studio, right?

It’s funny, I’m a really polite person but I can’t resist sharing my opinion when it comes to my own work. There were literally first cuts of trailers that didn’t have Amanda Seyfried in them — so you didn’t understand that she was the main character. And she had just come off Mamma Mia, and she had a very, very funny and memorable role in Mean Girls, and people just liked her so much as an actor. So it was really kind of startling to me, to see that they weren’t including her in the marketing materials because — while you could argue that the star is Megan Fox — the main character is really played by Amanda Seyfried. It didn’t bode well for the rest of the process, those initial trailers. It started to feel pretty weird, pretty fast. There were moments where I just knew that they were not embracing the female-centric team, creatively, behind the movie. They weren’t particularly respectful, in my mind, of the roles that the two female leads were playing, because they were sort of distorting the meaning of the movie. I feel like what I was most disappointed by was that it didn’t seem like they believed in the female audience. It’s almost like they didn’t want to sell the movie to women, without really acknowledging that the story is about — yes, it’s about a beautiful girl who gets possessed by a demon, but one who eats boys, who pulls their intestines out of their body. It was a weird crossed-wires kind of a situation, where I felt like departments weren’t really talking to each other to understand what the movie was that they were marketing.

There was that infamous email you got from the studio about the poster’s tagline, which had proposed something about Jennifer’s taste for bad boys.

It was so caveman, so kind of Neanderthal in its language, that I’m honestly having a hard time recalling the exact over-simplicity of it, but it was something like [adopts bonehead voice] JENNIFER HOT SHE EAT YOUR BOYFRIEND. [laughs]

“Jennifer Sexy She Steal Your Boyfriend,” I think it went.

Yes! It was almost like they couldn’t even be bothered to write complete sentences to us, which — if you know me at all, I’m not a fan of today’s casual patter. Even when I passed notes in high school I wrote in complete sentences and fully formed paragraphs. [laughs] So I’m just not a great candidate for receiving those kinds of emails.

Your director’s cut opens on Needy in prison, giving a much clearer sense of the fact that this is her story. What happened with the theatrical cut?

Well, it’s funny. You know, I appreciate both versions of the film, but I think my version is better. My version is probably more complicated, more complex. The opening of the film — the studio was hoping for something with less build up, and something that just pulled you right in some essential conflict. I’m not convinced [that happened]. I think the theatrical version does that as well. The biggest difference between my cut and that studio’s cut — or what I call the studio cut, because I was still very much in charge of that cut — was that my original cut spent more time focusing on the fact that these boys were actually really people, and that their deaths were meaningful. I think there was this idea that having the boys be actual victims that you felt something for, or that you felt the reverberation of a crime in this community — even in the heightened way that we treated it — it was considered a little too sad; too emotionally real. As a filmmaker, it’s very difficult to have people from the studio say, “It can be funny and it can be scary, but it can’t also be sad.” You sort of have to choose your genre mash up.

To me, that’s someone who hasn’t seen, say, An American Werewolf in London, which is funny and scary and also sad.

And that’s the thing. To me, I just feel a tremendous sense of responsibility in how I depict violence, and so it was important to me that the consequences be real. Unfortunately, in having to pull out a lot of that material around those boys, it just diminished, you know, the fact that the guys themselves weren’t bad guys. It’s not a revenge film; they’re not meant to be oppressive jerks. Actually the oppressive jerk is the guy who benefits the most — the guy who performs the ritual itself — and eventually he does get his comeuppance. But it was very interesting to recognise that that multiplicity of emotional threads was harder for the studio to digest.

The funeral, in the director’s cut, gives a sense of the lives around those boys, a tragedy beyond the main story.

Yes, and it’s funny because the script had always been about all of the boys as people who had parents. It never ended up in even my director’s cut, but there’s stuff between Roman Duda, the police officer played by Chris Pratt, not just finding Chip’s body but then delivering the news to Chip’s mom, and she sort of collapses to the floor. There was a lot of stuff in the movie that we didn’t have the space for — it was almost taking us away from other, more essential storylines. But the whole story, the whole screenplay, had been conceived to not just be about Jennifer and Needy, but about a world that gets turned upside down by this possession.

Rotten Tomatoes’ round-up for the week of release is headlined “Jennifer’s Body Is Hot, But The Movie Isn’t” — that was their distillation of the overall critical response. There were some positive reviews: Roger Ebert mostly liked it, despite calling the movie “Twilight for boys” and inferring that it was a shame Megan Fox kept her clothes on, while Robert Pattinson went shirtless.

[Kusama winces]

I’m sorry to make you relive this stuff! What are your thoughts on all of this? Was it the marketing people’s fault for selling it as a ‘hot girl revenge’ movie to a straight male audience, thus leading reviewers to see it in a certain way?

I think it was a classic bait-and-switch marketing move, this idea of getting the audience in to the theatre and then not giving them the thing you said they were going to see. It coloured so many responses to the film. The way that it was marketed often coloured the way female critics reviewed the film, and [they] assumed that I was sort of working for the man by making this film — which to me was a real disappointment, because I think the movie clearly has its origins in a feminist statement. I’m a feminist, Diablo’s a feminist; I think it’s so obvious that we care about girls, and love them, and love the young people we depict, and showed them with respect within the frequency we were working — it’s crazy horror-comedy, so there’s a lot about the script that was always politically incorrect, but that’s comedy in many respects. So I was disappointed at how the framing of the marketing framed the entire conversation around the film, and the film itself is one of the first casualties of that process.

It must have been satisfying to see a strange surge of interest in the film recently — with reappraisals in places like Vice, Buzzfeed, and Vox — however many years overdue they were. Where do you think this apparently sudden appreciation has come from?

I think there were some people that really loved Jennifer’s Body when it came out, and with the sense of passion that young people, in particular, can apply to areas of their life that are misunderstood. And I hope that’s a testament to the fact that the movie was really trying to speak to those kids who would be passionate fans. Even before I really started doing press [for Destroyer, Kusama’s film released late 2018], there was something about the Brett Kavanaugh hearings in the United States that had a spooky sense of déjà vu. The most powerful perches in the world, we see yet again, are being filled with credibly accused predators. It’s a dark time in America. I had a lot of friends who said, “It’s so weird, I saw Jennifer’s Body again — I felt like I needed to watch it again,” and it came off of those hearings. It was just a feeling, of having a President of the United States who just admits freely to assaulting women and not caring. There was just something about — I’m gonna just say it — the evil of it that made them think, ‘Maybe I should revisit that movie that made me feel uncomfortable, or laugh, or made me feel, in a way’; a film where women are being victimised by men, and then they’re victimising each other in this system. And the proof of that was watching female senators on the Republican side vote this guy to a lifetime appointment on the Supreme Court. So I just wonder if it was the confluence of political climate and current events, with just the sense of how rare it is that you even see movies like this, with girls at their core, who aren’t part of franchises. It’s probably one of the few movies that people could revisit of its kind.

It’s interesting you bringing up a system that drives women against each other. Looking at some of the criticisms of the film, from female writers at the time, Kira Cohrane in The Guardian said words to the effect that ‘in the end, it’s just another catfight between girls’ — but what you point out, and what comes through in the movie, is the environment that’s driven Jennifer and Needy at each other’s throats. That’s not exactly an anti-feminist approach.

No, not at all. And I’m sorry, but I take my genre movie rules seriously. There’s no [other] way to banish the demon. She’s possessed, so the only release that’s she’s going to have is to at least be restored to human form in death. I mean, I personally feel like, if you’re not a fan of the genre — I get it — but I hate having my movies reduced like that when people haven’t done their homework [laughs], or care about the genre they claim to comment on, or be critical of.

Surprisingly, a lot of critics don’t always do their homework.

[laughs] Yes exactly!

The general impression seems to be that, although there were mixed responses across the board, the male reviewers had it in for Jennifer’s Body more. Certainly there were, and still are, so many more of them, which has lead to some long-overdue discussions about gender parity in film criticism. Do you think things are changing, in so far as at least there’s an awareness of the need for more voices? And do you think those new, often younger voices, may have factored in to the newfound appreciation for Jennifer’s Body?

Yeah, I think that’s completely possible. There is such an imbalance within the critical community — of women’s voices, of people of colour’s voices — and so it has been something we’re starting to pay attention to. I still think power rests with older white men, and they continue to get their long-running high perches. And they keep getting placed at other high perches, when everything gets shifted. One conglomerate shifts into another, and it seems like these guys just move around from one place to another, whereas women are often driven out of being film critics. This is an interesting moment, where we have to consider all kinds of factors in how movies are perceived and absorbed by the culture. There were, in my memory, almost no women in the marketing team when they were marketing Jennifer’s Body, and so that created a real cognitive dissonance, because there seemed to be a lack of understanding from the beginning of what the movie was. I think this is something that filters out to everything, when you think about how few women are the heads of festival juries, or how infrequently they’re on the selection committee for world-class festivals. It’s disheartening, because there are so many doors that get opened for a lot of filmmakers, but not if the people who are the gatekeepers don’t see how your film relates to them. It’s a tough one.

You’ve also expressed misgivings about being labeled simply a ‘female filmmaker’ and being put in that box, and obviously when Jennifer’s Body came out there was a lot of focus on you and Diablo being a ‘female’ creative team. Has that situation gotten better, or is it something that you continue to struggle against?

I think the focus on me as a woman hasn’t really shifted — it’s only intensified, actually.

I mean, here we are talking about it.

Yeah. I understand why people want to have the conversation. There’s an absence of women at awards season — for the most part — when it comes to directors, and screenwriters, and producers, and within the craft fields, cinematography, and editing, and sound. There are so many ways that the great work of women has been overlooked. So I understand why people wanna have the conversation. But I get frustrated because the longer I have to talk about who I am — as a woman — the less time I feel that I end up having to really grapple with who I am as a filmmaker. Somehow the emphasis on the conversation on my female-ness starts to feel reductive — when clearly all of the women peers and colleagues that I have, we make very different movies from one another.

After your experience on Jennifer’s Body, and your well-documented battle with the studio on Æon Flux (2005), are you in a happier place now in terms of the work you’re making?

Yeah. I’m an odd bird in this business. I’ve yet to make somebody a ton of money. I’d really like to. [laughs] That’s another thing I’d like to say I’m able to do — to make somebody a movie that really makes a ton of money, because that’s a part of how you prove your worth in this business. But the fact is that I’ve managed to keep making movies, and I’m really hopeful that the reason is that the movies are good. [laughs] They’re not for everyone; I don’t make movies for everyone — I don’t know how — but I do make movies that I hope speak to somebody. And I’m so fortunate to be able to keep doing this. I’m quite grateful that I’ve managed to keep hustling, and keep a career alive.

Well when you’ve made something like Jennifer’s Body, you’ve made something that’s speaking to someone, which — in the long run — matters more than whatever blockbuster, like Revenge of the Fallen, made the most money at the time. And I don’t mean to disparage Michael Bay or anything!

[laughs] I think that’s true.

Maybe the film that makes money is a sequel to Jennifer’s Body? Did you ever consider one?

I mean, it’s hard for me to really see it. I think there was the hope that the movie was gonna do well. I can’t think of a ton of sequels that I love.

Like, there was talk about a sequel to Heathers for years, but some things are just best left alone in their perfect little glow.

Yeah. And I mean, Heathers was a huge inspiration for this movie — which I think is obvious — but you know, to me Heathers was a great example of a truly weird movie that, when I revisit it, every time I’m like “I cant believe how strange that movie was.” But it spoke to me so deeply in terms of that mixture of tones. It’s a hard thing to make movies that, you know, make you laugh and then kind of make you cry, and make you scared — that’s not for everybody.