Ben Ferris is the creative director of the Sydney Film School, and the founder of independent arts company Artemis Projects. His new film, 57 Lawson, is a docu-fiction drama set in a housing development within the same inner-city region as the School. Ferris encountered the building on his daily commute, and seized the opportunity not just to tell its occupants’ stories, but preserve a side of the city being slowly drowned out by corporate interest and redevelopment. The film’s slow cinema-inspired approach of having stories unfold through the abstraction of static frames is a follow-on from his exploration of film language under the Artemis banner; a fusion of the filmmaker’s interests as well as truth and fiction. Ahead of the film’s premiere at the Sydney Underground Film Festival, I spoke to Ferris at the Rag Land Cafe, a favoured haunt of his students, about his influences and hopes for the project as an egalitarian document of the city’s history.

Do you see any kind of creative balance you have to strike between Sydney Film School and your own creative endeavours, or is it all just part of one continuum?

There’s always a bit of a tension because, as artistic director, I’m full time at the Film School. With my previous film [2009’s Penelope], not for this film, I arranged a sabbatical, so I had a chunk of time away from the School and was able to go away and film that in Croatia. This film was different because I filmed it over a two-year period, so I was shooting it in and around my other commitments to the Film School. I’d be shooting on weekends and evenings, and that was the nature of this particular project. But I guess for me, as a teacher at the Film School, I have a desire to keep being active myself. It’s something that we try to encourage culturally at the film school, because I think students in the classroom are pretty good at sensing whether someone feels current or whether they’ve just been teaching for a long time and haven’t been practising.

Was that at least one thing that inspired 57 Lawson: staying current, and staying connected to where you were situated professionally?

Yeah, absolutely. I cycle to and from work, and every day I pass through the housing commissions. It just captured my imagination. Also, having been here for 12 years in this particular space, observing the changes in the area, I’ve always been fascinated by that. And then, about two and a half years ago, I felt in my bones that there might be some significant change coming, and I had a window of opportunity to record life in the area before things change too much.

You mention in the quote that SUFF has in their program that the film is an archive of a city, and of a Sydney that you’ve almost forgotten. Why it is that you’ve almost forgotten?

I guess the film’s a bit nostalgic in a way, for a Sydney that I remember as a child. I’m not ancient, but having seen the city undergo tremendous change and largely through significant amount of new developments, I feel is changing the character of the city significantly. When I’m talking about a city that I’ve almost forgotten, in a sense, the city’s been changed in a way where it won’t be the same.

I imagine the people are very closely tied to that—do you feel they’re in danger of being forgotten?

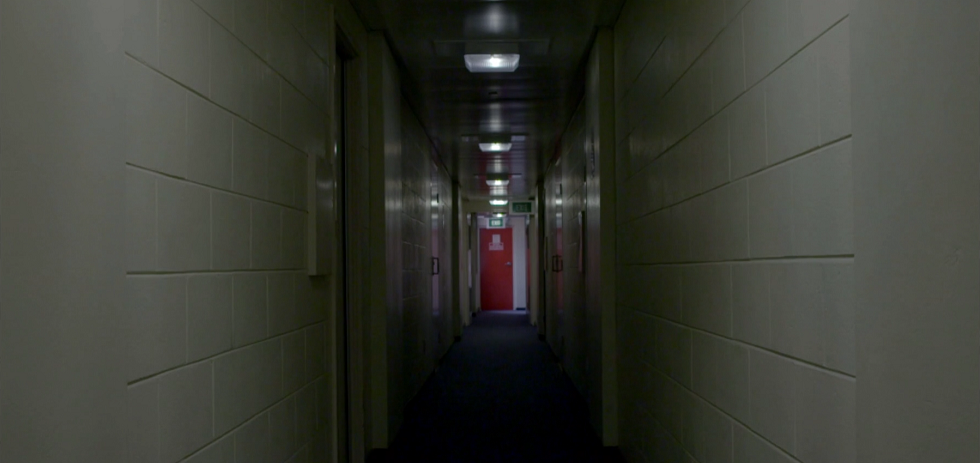

Yeah, I mean… I think one of the things I’ve tried to capture in making the film—and I think it’s there—is the idea that, when you’re looking at the film, it already feels like an archive. It feels like you’re looking at something that has since been gone, and that includes both the space and the people in the spaces. I think hopefully you get that feeling.

It would strike me like the most typical archival process in film is to just point and shoot—Super-8 reels, or what have you. Could you talk a bit about how that element of fiction assists in that process, and why that was a vital part of that archiving and remembering process?

That’s a really good question—if it’s an archive, why don’t you just simply document it? Why do I feel the need to have a fictional element? Without giving too much away about the film, essentially I was shooting the film in anticipation of a particular event, which is the relocation of the tenants from this area. It’s just been announced recently, you may know, that that whole area that we’re walking past there is gonna be completely redeveloped…

…and you knew that going in?

I didn’t know it, but I had a strong feeling that it might happen. It’s very valuable land; very central, significant amount of land, there’s a lot you can do with it. A lot of developers have gotten extremely excited about it. This area across the road from us is gonna become a massive train station development, so that becomes Waterloo train station; a bit like Green Square. In a number of years, it’ll be just totally unrecognisable; brand new high-rises coming up through there; higher density than Hong Kong and Singapore. So I didn’t know, but I had a strong feeling. At the time of filming, that development hadn’t been announced, so the fictional element is anticipating an event that I felt might be coming, but then to make it feel as documented or as real as possible, it’s that hybrid thing.

It sounds like you’re perpetuating that scenario as a way of dealing with it better, as a way of dealing with the idea that these people are gonna be brushed away or relocated. Is that something of a cathartic process for them? Did you pitch it to them in that way?

No, that’s interesting. It reminds me of, on the extreme scale, The Act of Killing…1

Right, yeah.

…takes catharsis to a whole other level; fictionalisation in a documentary context and catharsis. Yeah, but not so much in this case because while the tenants were aware that relocation was happening in Miller’s Point, I think it’s the sort of thing that unless it’s actually happening to you, you don’t necessarily contemplate as a possibility, so none of the tenants that I worked with genuinely considered that it was a possibility.

Did you end up having to communicate to them that that was what you were anticipating? Was there ever that moment?

Oh absolutely, I was very up-front about that but… I guess the thing to think about is that some of these tenants have been there for a long time, like 40 years plus in some cases, so the idea that their life can change so significantly after that amount of time is hard to process; hard to compute. And when it’s a filmmaker coming in and talking about a fictional scenario, it plays into that. It’s a fictional construct. Turns out that it wasn’t, but it does blend those things together.

It would be so tempting, at least from my perspective, to infuse that slightly “activist” angle to it; to bring people’s awareness to that certain issue. How much does that play into the film for you? Was that something you avoided or embraced?

It’s not a primary focus for me. I wouldn’t brand myself as a political filmmaker in the classic sense, and the film is not that film. I’m very interested in aesthetics, I’m very interested in process, so those things are very, very important to me. The situation in the frame, I am very interested in. Rather than being revved up about a specific issue, it was a way for me to explore what I think is a broader issue about where the city’s going more generally, where our culture’s going more generally. So it’s a way into broader issues about home, and displacement in a country that’s founded on some of those issues that we’re still trying to grapple with.

Do you embrace that to make the film a bit more timeless as an archive, so that it’ll work for people more assuredly in a few years’ time, or longer?

Yeah, I hope so. Every filmmaker hopes that they’ve got a lasting value. It’s certainly my ambitions for it. I guess the archive thing, it’s a comment about Sydney more generally at a particular time and place; at a particular juncture in its history, where certain aspects of its character are being eradicated in what I feel is an irreversible way.

Right after the screening, you’re giving a masterclass on documentary fiction and a demonstration of your working process, which I think is really fascinating. I’ve heard directors talk about their processes, but never demonstrated necessarily. Who do you take as your subjects? Is it people in the class or people you specifically bring along?

I’m anticipating I’ll bring a couple of the people that I worked with in the film, so either the tenants… most probably the actors will appear, and then I’ll involve members of the workshop to interact, and we’ll devise some scenarios, to sort of replicate or emulate the process that I was using on the film.

It’s interesting, the word “emulate”… people already find that fictional remove from reality within the film itself, but how do you see this demonstration fitting in that sort of environment? Does it add another layer of fiction? How do you frame that?

For a start, the workshop was a way of framing the film, because it’s very easy to read 57 Lawson as a straight documentary, and if you’re not on your toes, that’s how you’re gonna read it, so by framing it in the hybrid context, I wanted to draw attention to the fact that not all is as it seems as a viewer, and it’s subtle, it’s subtle.

Do you anticipate there’ll be some people who’ll come to the workshop who will maybe have that understanding or some other misconceptions about documentary fiction that you want to clear up?

Well, I was talking more about the way that my film is presented could be easily read as a documentary, as a straight documentary, because the fictional elements are quite subtle and quite disguised. But I guess one of the questions that I’m interested in; why I was interested in making the film—it’s an age-old question that we’ll explore in the workshop—is where you’re constantly invited to question that line between fact and fiction in the context of representation. I’ve always found those sorts of works like… I don’t know if you’ve seen Silent Light by Carlos Reygadas?

I’m afraid not, no.

It’s the kind of work… Chantal Akerman does it as well in All Through the Night [French: Toute Une Nuit], for instance, or even Jeanne Dielman to some extent, where she’s constantly raising that tension between document and construct.

You’ve travelled around the world to attend and show your films at festivals. Have you often given classes and lectures in that festival environment specifically?

Yeah, I have actually, and at a couple of festivals overseas. Is there something unique about the festival as a learning environment you mean?

Yeah, and thinking about the perspective of someone attending, how it fits into their day.

I mean, for a start, with the Sydney Underground situation, you’re competing with films at the same time, so as a participant of the festival you’ve got to really want to do a workshop as opposed to seeing the festival. If it ties in, the ones that have worked the best for me are the ones that tie into a sort of narrative over the course of the festival, that enriches that curatorial narrative, whatever that might be, takes you deeper into that. That act of curation, and the workshops are supporting that, and could be really interesting for a participant.

The typical route for that is sort of a Q&A. Are you doing one for 57 Lawson?

I’m doing a brief one after the film.

So that level of interactivity that the masterclass grants—is that tied into anything with the mission statement of 57 Lawson; the remembering process?

That’s interesting… I guess I could have done it as more of a Q&A or talk or something. There’s something about seeing a process in action that I personally always find interesting. I can observe the way a filmmaker works or constructs a scene or interacts with actors. I find that a really direct experience, it’s more experiential. And also, maybe it’s just offering up something different, and potentially too, in terms of the hybrid, I didn’t want it to just become… the hybrid thing is really fascinating, but I didn’t want it to just become an academic/analytical/philosophical discussion. It could easily get bogged into that, but through demonstrating it and seeing it in motion, one might comprehend it in a more direct way.

Have you had that feeling in some Q&As or festival events where you’ve wanted that process demonstrated? Does that kind of play into it as well?

Yeah, I think once you’ve been to a lot of Q&As… I always find it fresh if something can be demonstrated or shown rather than just spoken about. It can get a bit abstract. It was a way of embodying the idea.

And you mention academia, I did notice that scholarly study and academia is part of your life as well. I notice your company is called Artemis Films—is that [classical study] something you keep close to your chest as far as your creative outlook?

Not really. All of my work is based on a lot of research. Usually either it’s research about a topic or a myth. But then I’m also very interested in language, film language, so usually my filmmaking is an unravelling of some of those thoughts that I’m having about film language; finding a way of exploring those ideas.

Is cinematic language just another language, or is it a way of surpassing the barriers that [ordinary] language might present?

Yeah, cinematic language is as a syntax a grammar and codes as much as any other language. How you unpack that is quite interesting for me.

And in the case of 57 Lawson, what kind of precedents were you taking in terms of expressing yourself in the form? Just going off the trailer, it looks like static shots that soak in the environment—a bit of No Home Movie. Some people would ascribe “slow cinema”.

I’m very much in that school and very influenced by Akerman and that tradition of hyperrealism and minimalism where you… and how far you can push the minimalism, to a point where it starts to abstract. That intersection between observed reality, observed objective reality and then through duration—it’s starting to comment on itself in a way, which for me suited the hybrid approach, where you’ve got the objective reality of the document and then a slight abstraction happening with the drama, with the fictional side of things. It’s a blend of those things. Definitely I’m interested in curation and slow cinema, and I am generally as a filmmaker, in this particular context, I guess it starts to, I think its function is a function of defiance. I’m talking about the preservational nature of the project, the archival nature of the project, so the slowness plays into that.

Is it a matter of absorbing more detail so it can be more singular as a document?

Yeah.

And that’s particularly what Sydney needs? Do you feel that there’s a lack of that?

Yeah, I sort of… it’s a very, very subtle I suppose pièce de résistance that expresses its resistance through its slowness. That’s reacting in the context of hyper-movement and hyper-development.

Countering the rapid change that’s happening.

Yeah. So that’s the thematic function of those choices.

Running the Sydney Film School and making a film like this, you’re making it your life to plant roots in Sydney specifically. After this many years, can you even anticipate what impact you’re going to have on the fabric of the city? How do you feel about it as you’re doing it?

And by impact, you mean…

As far as your impact to create something that documents the city, whether it’s the work of your students or whether it’s your own work.

I’m interested in the work of Chris Marker, and I wrote a piece for the Cahiers Lumiere in Paris, about this particular issue, which is archiving a place and a time through student films, and what student films are observing, recording, and obssessed with over periods, and how that might change. The concept is “does that communicate with the zeitgeist, and is it a kind of living archive?” Chris Marker’s interesting for me because in Remembrance of Things to Come, he looks at threading in those alternate histories by archiving the lesser-known moments from history, so it becomes a sort of grass-roots egalitarian vision of history not dominated by a dominant mantra or narrative that happens to be popular or propagated. So that’s something that I’m very passionate about and think about, and I hadn’t really made the connection but…

…that it’s a collective act of remembering that’s happening in Sydney Film School?

Yeah.

I think that wraps it up. It’s really interesting and I’m really looking forward to seeing the film. It sounds fascinating. I can’t think of anything that’s quite like it.

Cool.

Thanks for telling me more about it.

Thanks for taking interest!

57 Lawson receives its world premiere at the Sydney Underground Film Festival on September 17. For more information on the film and masterclass, and to buy tickets, go here.