You Have To See… is a new weekly feature here at 4:3, where one staff writer picks a film they love and makes a group of other writers watch it for the first time. Once this group has seen the film, the suggestor writes a piece advocating the film and the others respond below.

Whilst not explicitly spoiling the film, the article is detailed. We would recommend seeking out and watching the film each week, then joining in the debate in the comments section.

The Endless Reflections of Inland Empire

It’s easy to forget now but Inland Empire was relatively well received when it was first released. Roger Ebert’s website gave it a rare four stars (from the man who hated and remained hateful of Blue Velvet) and it made several end of year (and end of decade) best-of lists.1 Yet in the six years that have seen Inland Empire remain as David Lynch’s latest film, there have been few cults to spring up around it. While Eraserhead, Lost Highway and, to a lesser extent, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me all received serious re-appraisal and attracted hardcore fans after their initial dismissals, Inland Empire has become the maligned embodiment of Lynch’s opaque indulgence. All those who felt alienated by Mulholland Dr.’s resistance to conventional narrative and Eraserhead’s dark surrealism were now vindicated by a film that even the director’s most ardent fans had to admit was a hard film to enjoy. The emperor had no clothes. David Lynch was indeed a wanker all along.

I’m here to argue that Inland Empire is at least fascinating, and at best a masterpiece, but I won’t dismiss those who simply can’t get into it. While a lot of other Lynch’s films reveal a rather tangible set of themes, characters and perhaps even narrative if you are open minded enough, Inland Empire is impossible to penetrate completely. Three hours of free-associating surrealism is never going to be an easy experience and even I’ve never been able to get through it in one sitting. Yet digging into the world of Inland Empire can be an extremely rewarding experience.

We begin Inland Empire with a recording. Not a video recording but one of the oldest forms of technological reproduction, an old Shellac gramophone record playing one of the oldest radio plays in existence. From there we are introduced to “The Lost Girl” a distressed figure trapped in a room, crying and glued to a television scene. A brief glimpse of the main ‘plot’ flashes across her screen before diving into excerpts from Lynch’s perverse series of shorts, Rabbits.

Why is the Rabbits scene so striking? Why do these long stretches of static camera work, devoid of human faces, coherent dialogue or conventional action mesmerize and unnerve us? It’s more than simply the unexpectedness (otherwise their repeated appearance would be intolerable) but the way Lynch takes apart the components of the domestic sitcom and awkwardly reassembles it to destabilize the relationship between the viewer and the image. To create a dom-com all you need are human subjects, dialogue, a camera that gives us a clear view of the three walls we’re allowed to see and to makes things easier a laugh track that informs the audience’s desired reaction. That is all here but the subjects are robbed of humanity, the dialogue is a disjointed mess of unrelated statements, the camera shows all but never moves to the point of discomfort and the laugh track merely further confuses the relationship between what the screen is telling us and what we are meant to feel. By blurring the increasingly conventional language of screen media, Lynch forces us to confront the apparatus that we take for granted. By mixing up visual language slightly, the viewer is forced to think about what the camera does and, in a culture that is so concerned about what images and dialogue signify, it’s a step we too often skip.

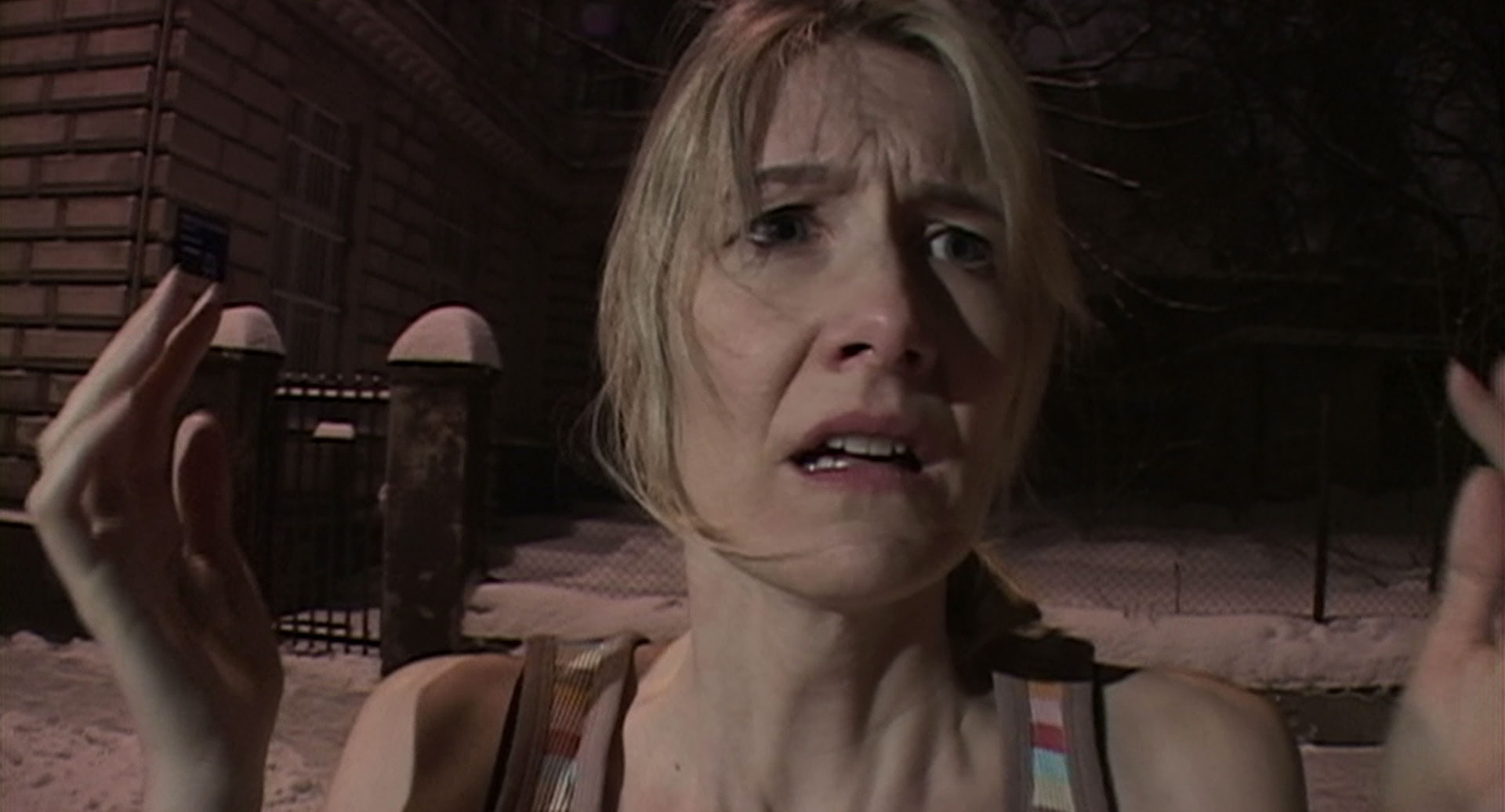

Inland Empire spends the remainder of its three hours drawing attention to the overlooked relationship between the viewed and the viewer. TV screens and movie theatres pop up intermittently to replay events to characters but even without these diegetic allusions to reflections and recordings, Lynch’s strange camera draws enough attention to itself. Inland Empire is extraordinary because it forgoes the carefully constructed surrealist set pieces of Eraserhead and lets a roaming DV camera do all the work. There are few ‘tricks’ in the form of special effects or sets because the act of recording, of reproducing with a camera, even one of the cheapest and most accessible cameras available, is a kind of trick in itself. Some of Inland Empire’s most memorable images simply involve ordinary faces turned into grotesques by a slightly unusual camera angle. The terrifying moment of Laura Dern slowly running in the dark towards the camera cannot be qualified by any conventional film criticism. It is a reminder that our over-reliance on conventional visual language often cuts us off from appreciating some of the inherently perverse aspects of what a camera does.

In a certain way, then, Inland Empire is the postmodern bookend to Eraserhead. Where that film reflected anxieties of industrialization and the dehumanizing effects of mechanical capitalism, Inland Empire shows a fracturing identity in a world endlessly reflected and refracted through the ubiquitous presence of screens. Scenes in Inland Empire constantly return from different angles, planting seeds in one moment to return to them fully grown an hour later. Nikki’s sense of identity constantly begins to fragment in synchronization with our increasing uncertainty of what is a representation of reality and what is a representation of the cursed film-within-a-film. Of course it becomes clear that this doesn’t matter, because as long as we observe these events they will merely be an off-kilter reflection of what the camera perceives as real. One of the climactic moments that reveal that at least some of the increasingly insane series of events we have been witnessing were indeed being filmed by Kingsley (Jeremy Irons) could feel like a bit of a cheat. But it really makes no difference, if Kingsley’s camera weren’t there than David Lynch’s camera would be, our observation of Nikki/Sue’s spiral is so tainted by what the camera lets us see that it feels more honest for the film to throw caution to the wind and write off a good chunk of the film as ‘fictitious’ because it’s all fictitious in the end.

Which is why David Lynch’s controversial decision to film Inland Empire in standard definition digital video is quite brilliant. Apart from the freedoms it allowed him, the poor dynamic range of the camera makes its effort to reproduce more strained and warped to the point that it almost feels sentient. When Nikki/Sue’s ‘husband’ spills ketchup on his shirt, the scene lingers as she seems transfixed by the red mess he’s covered in. The obvious connotation is blood, and because the camera does not have the detail to distinguish between the two, they become essentially interchangeable. The camera decides what we view, an obvious observation, but it can also decide how we view it. One of my favorite scenes in the film comes towards the end when Nikki is stabbed and left to bleed out just off Hollywood Boulevard. In one of the film’s more Mulholland Dr.-esque moments, she veers off the walk of fame to spend her last moments in the company of homeless cast-offs who lay just off the frame of the famed glittery Hollywood veneer. As Nikki painfully bleeds out the camera ignores her to focus on the bizarre story of one girl’s friend, Niko, who has a pet monkey and a hole in her vagina from turning tricks. The camera takes the neo-realist idea of the dislocated camera and turns it up to eleven, ignoring the pivotal moment of the main characters death to indulge a sad story from a narrative nobody. Yet there’s something profoundly humane about Lynch’s cheap, subversive camera swinging away from the walk of fame to tell the stories that are never told (not that I’m suggesting vaginal holes and pet monkeys are a crisis in LA).

Inland Empire ends with a meeting between Nikki and the Lost Girl who has been watching her, freeing the Lost Girl – the subject and the viewer reconciled at last, the viewer unburdened for their trance. It’s a touching moment, even if its hard to understand exactly why. Inland Empire doesn’t need you to understand it; it just demands that you consider its own apparatus. Lynch boldly reconsiders the role of the camera in a time when they are more omnipresent than ever. For what could have been a tedious Warholian concept piece, it’s a gloriously stimulating film that provokes our most basic instinctual responses while firing up our intellect.

Responses:

Conor Bateman – David Lynch has made a horror movie, of sorts. Piggy-backing off of dark and disturbing sequences in Lost Highway and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, his most recent feature film is intermittently terrifying, with his masterful ability to pull focused tension out of thin air once more on display. That’s not to say the film, as a whole, is necessarily fantastic. It has its moments and its nightmarish dream-within-dream-within-film-within-film works for the most part. Dern is good but I struggle to say she was great, exaggerated emotions and panic only get you so far. The entire usage of Poland, as both narrative arc and setting, was haphazard – the sepia-toned parallel narrative worked but the travelling circus/Dern’s husband subplot was an unecessary mess. I found myself wanting less plot, more ambiguity. Don’t let me figure it out, don’t make me want to try – embrace the inner Steve Erickson and Jesse Ball and fully go down limitless rabbit-holes. That’s when the film was at its best, moving quickly from concept to concept, rooms and doorways crossing space and time, earlier scenes looping in on themselves.

Saro wrote about that “the terrifying moment of Laura Dern slowly running in the dark towards the camera cannot be qualified by any conventional film criticism”. I disagree. Here’s an indulgent aside in which I attempt to do just that. This may be the best sequence in the film, outside of the Rabbits interludes, and it is the best because it plays with image and sound both within and without the frame. The image of a cartoon clown’s face fades as a bright light on a tree branch takes over the center of the frame. We see a figure, instantly recognisable as Dern, in the medium distance, walking along an outdoor path. The bright stage spotlight on the grassy path creates an unsettling merger of the natural and the constructed. Dern walks towards us, or at least appears to be walking. As she turns the bend, though, we realise she is moving fast but the speed of the image is slowed down, creating the impression of somewhat normal movement. We get the distinct impression that something weird is about to happen. Almost as soon as this realisation hits, the film speeds up, near teleporting her to the front of the frame as music blares. Because our eyes and minds have only barely adjusted to the slo-motion concept, the suddenness of the shift is shocking. On top of a purely aesthetic level of engagement, what this realisation-to-horror movement reminds us is that we are trapped in this film at Lynch’s peril, even if we figure out what is going to happen right beforehand. As the Winkies scene in Mulholland Dr. shows us, Lynch can give us the ending but that won’t dampen the impact.

Jessica Ellicott – Thank you Saro for forcing me to watch this film. Despite being a big Lynch fan, I had yet managed to summon the courage to face his by all accounts deeply disturbing Inland Empire. Knowing that I would have to sit down and write something afterwards allowed me to take on what turned out to be three brilliantly dark and perverse hours of my life. However, I still feel ill-equipped to put into words a response to the film, as any attempt feels fraught with misrepresentation. It’s a film that is better experienced than dissected.

Lynch reportedly had the most creative control on Inland Empire that he’d had on a project since Eraserhead, and I think it shares much with that film in its relentlessly daring approach. To me, the film is the extreme culmination of the themes and motifs that pervade Lynch’s body of work – for instance fractured identity (as Saro mentioned), the unconscious world of dreams, nightmares and desires and the perversion of Hollywood and the American Dream. Its glimpses of signification lead you down the garden path into thinking you can make sense of its world, or reach some kind of conclusion about its message. I think it is Lynch’s ultimate mystery.

Imogen Gardam – I have to admit that I hadn’t seen any of David Lynch’s work before seeing Inland Empire, and I still haven’t decided if that’s an advantage or a disadvantage. To be honest, when dealing with such an oblique and unquantifiable film as Inland Empire, that’s too clear cut a concept to really bother with anyway.

Quite early on in the film Grace Zabriskie (credited mysteriously only as Visitor #1) visits Laura Dern’s Nikki Grace in her house. During this scene, Zabriskie is filmed in close-up, her face so close to the camera as to almost be distorted, given a strange, slightly fish-eye like effect. When the camera cuts to Dern, however, she is filmed as if being interviewed by Vanity Fair or the Hollywood Reporter, with clear resolution and a comfortably distant frame. She is lit from behind by a lamp and the shot is composed of clear thirds that are almost comfortingly familiar after the low-fi close-up of Zabriskie. I felt like I suddenly had a handle on the film – as if I knew what Lynch was trying to do, what he was drawing on: the cultural signifiers of a fluff celebrity interview intercut with a strange fortune teller to make some commentary (I hadn’t quite decided what yet) through their uneasy juxtaposition. Then the scene, and the film, continued – events became more bizarre, less logical, harder to follow. The “plot” I was clinging to and trying to process in my mind became more oblique and at a certain point, I gave up. Instead, I sat back and let the barrage wash over me. As Dern ran towards me in the dark, I let myself be terrified without trying to link the scene to anything else – in a way I connected to the film on a deeper level, allowing myself a more basic reaction to the images on screen. I’ve intellectualised about it since, and I will continue to do so for some time – it’s a film that stays with you. The Lost-Girl-cum viewer may certainly be freed by the end of Inland Empire but I didn’t feel that I ever was. It was a rare, unfamiliar and strangely joyous experience to be completely lost in Lynch’s world

Jeremy Elphick – Inland Empire definitely comes off as one of Lynch’s strongest works to date, but it remains one of his most criminally under seen films. The hardest part of the film for me was finding 3 hours to watch it, and although once I found the time it flew by, it’s clear that this length has contributed extensively to the exclusivity of the film. Outside of the running time, Inland Empire is a fierce culmination of Lynch’s body of work. This positioning of the film as something that draws and builds on the entirety of Lynch’s career is established as early as the usage of Rabbits towards the start of the film. As Saro mentioned, the use of standard definition digital video is immediately prominent and creates a rare artificiality in modern cinema; something that makes Inland Empire not dissimilar to one of Lynch’s favourite tropes: “the soap opera”. At the same time, there’s an intense thread of the inimitable Lynchian surrealism that is able to leave the viewer simultaneously unsettled, confused and mystified without ever being entirely aware of why. There’s plenty of contemporaries of Lynch making “surreal” films, but Lynch’s strict adherence to a very dreamlike style of surrealism akin to his earlier work with Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet remains pure in Inland Empire. Alongside this markedly Lynchian surealism, a very distinct soap opera-esque standard definition, and a constant appeal to the element of unease in horror in the vein of Lost Highway, Lynch has made a film with Inland Empire that possibly serves as the most comprehensive statement of his output to date. I still don’t think it’s the strongest Lynch film by any measure but I do believe it expresses the most holistic presentation of what a David Lynch film is. It’s running time is intimidating, but it’s easily worth watching, and if you’re a fan of Lynch you’ll probably love it. I did.

Inland Empire is available on DVD from Madman Entertainment and on UK blu-ray from Optimum Home Entertainment.

Next week on You Have to See… we look at Jerry Lewis’ classic The Ladies Man