“It’s just shit innit? But it’s important shit… to me”

One of the most problematic sub-genres in film is the rock documentary (or rockumentary). Great concert films make the most of the musical skills of their subjects but really cease to hold any value beyond their subjects and those that manage to find a narrative to engage people that don’t care for the artist on display usually stop being about the music, which is what justifies the project in the first place. There have been numerous attempts to overcome these hurdles by fusing fact with fiction but when the actual artist is involved it usually veers closer towards Led Zeppelin’s hilariously misguided The Song Remains The Same than Todd Haynes’ masterful Bob Dylan anti-biopic I’m Not There. Yet 20,000 Days On Earth may have finally gotten it right, with an approach that is more ambitious than the immaculate concert and recording footage gathered but refreshingly aware that everything Nick Cave has to offer is ultimately rooted in his art.

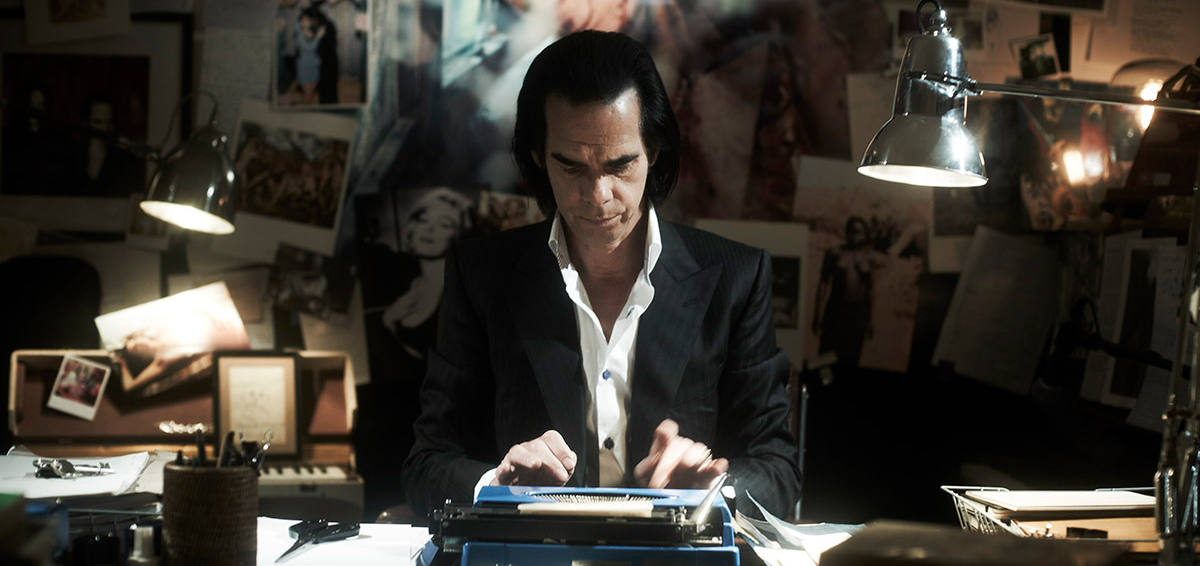

As it’s title suggests, the film reconstructs (there’s little pretense that the majority of the movie is any less fictional than A Hard Day’s Night) a day in Cave’s life, supposedly his 20,000th all up. At first it seems like a simple gimmick to find an organizing principal for such a loose film but as the central themes come into focus it takes on a more important meaning. The man we see before us is overall a series of memories, he says so himself in a conversation with a psychoanalyst Between reminiscing with ex-Bad Seed Blixa Bargeld, a trip to the archives and wracking his brain for disjointed younger memories for his psychoanalyst; Cave uses his 20,000th day mainly to reflect and dissect the first 19,999. He’s a refreshingly frank but articulate subject. Eschewing the usual rock star archetype of either massively egotistical or self-consciously modest, Cave speaks of his past the same way anyone does when confronted with old relics, aware of the solipsistic curiosity it fires up in him but willing to open up to anyone who listens, which in this case is a psychoanalyst, a team of archivists and audiences across the world.

If Cave spends half of the film living in the past then he arguably spends the other half living in the fictional world he as built up through his songs, novels and endless fragments of unpublished writing. The day Cave walks through feels like an extension of his work while we also see how it feeds into it. The film visually occupies the notebooks and scraps of paper covered in lyrical fragments and doodles only Cave can understand, as if they are a setting unto themselves. The soundscape of Cave’s home of Brighton is merged with embryonic demos from the then-forthcoming Push The Sky Away album. When not discussing the act of creation he is reflecting on the other side of his career – transformation. The act of performance for Cave is deconstructed through conversations with his friends and collaborators in car rides, revealing the emotional motivation and methodical process required to be a rock star. Of course this is all intercut with the actual footage of the worlds Cave is building, revelatory footage of the band recording and eventually a live performance at the Sydney Opera House. Fittingly the life that feeds the myth is fictionally reconstructed while the world created by his art and performance is the only documentary part of the film.

All this would not be enough if the formal qualities of the film weren’t strong, and they are nothing short of incredible. Directors Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard ‘capture’ Cave’s life fluidly and freely, editing Cave’s voice over in and out of the diegetic dialogue seamlessly while Cave’s driving companions don’t enter or leave the car they merely appear and then disappear in single edits, like ghosts. The extended sequences with the psychoanalyst and at the archives have the potential to be visually underwhelming but the pair create a sparse but captivating mis en scene, drenched in blue and green lights. One stunning sequence sees Cave recall the first meeting with his wife, the dialogue turning from prosaic exposition into a possessed rant about the incarnations of female beauty he has been exposed to. In the corner, a seemingly innocuous television springs to life with images to accompany Cave’s subconscious, the camera zooming in on it as his inner thoughts consume the artifice of reality Forsyth and Pollard seemingly care little for. This synthesized approach is what makes the film so overwhelmingly brilliant, it simultaneously occupies the real and imagined spaces of Cave’s world making the former transcendent while rendering the latter approachable. Much has been made about the films blurring of fiction and reality but its wise enough to not dwell on its formal innovations. Over the course of the film it becomes apparent that such an approach isn’t just a strong one it may be the only possible way of providing insight on a creative subject. It just unfolds without pretense, making up the rules as it goes along and in doing so casts a spell over the audience like Cave does on stage.

20 000 Days On Earth uniquely captures the life of an artist and how that feeds creation, and how a life well lived (heroin addiction aside) walks alongside our present selves in memory. It’s a film that places music, myth and persona alongside each together and respectfully does not try and separate them. I’m not going to pretend that the film’s merit isn’t tied up in how much you personally respond to Cave as an artist but that’s beside the point. To deduct points from 20 000 Days for its inextricable connection to Cave is like doing the same when reviewing a Bad Seeds album. This is Nick Cave’s world, as a performer and creator, in filmic form and if you are one of many convinced he is one of the most fascinating and consistent artists working in music or anywhere else than this film unquestionably delivers. The films final moments say it all, Cave staring at the front row of the Opera House, footage from past performances flashing across the screen, repeatedly howling “I’m transforming, I’m vibrating, look at me now!”

Around the Staff:

| Christian Byers | |

| Jamie Rusiti | |

| Conor Bateman | |

| Felix Hubble |