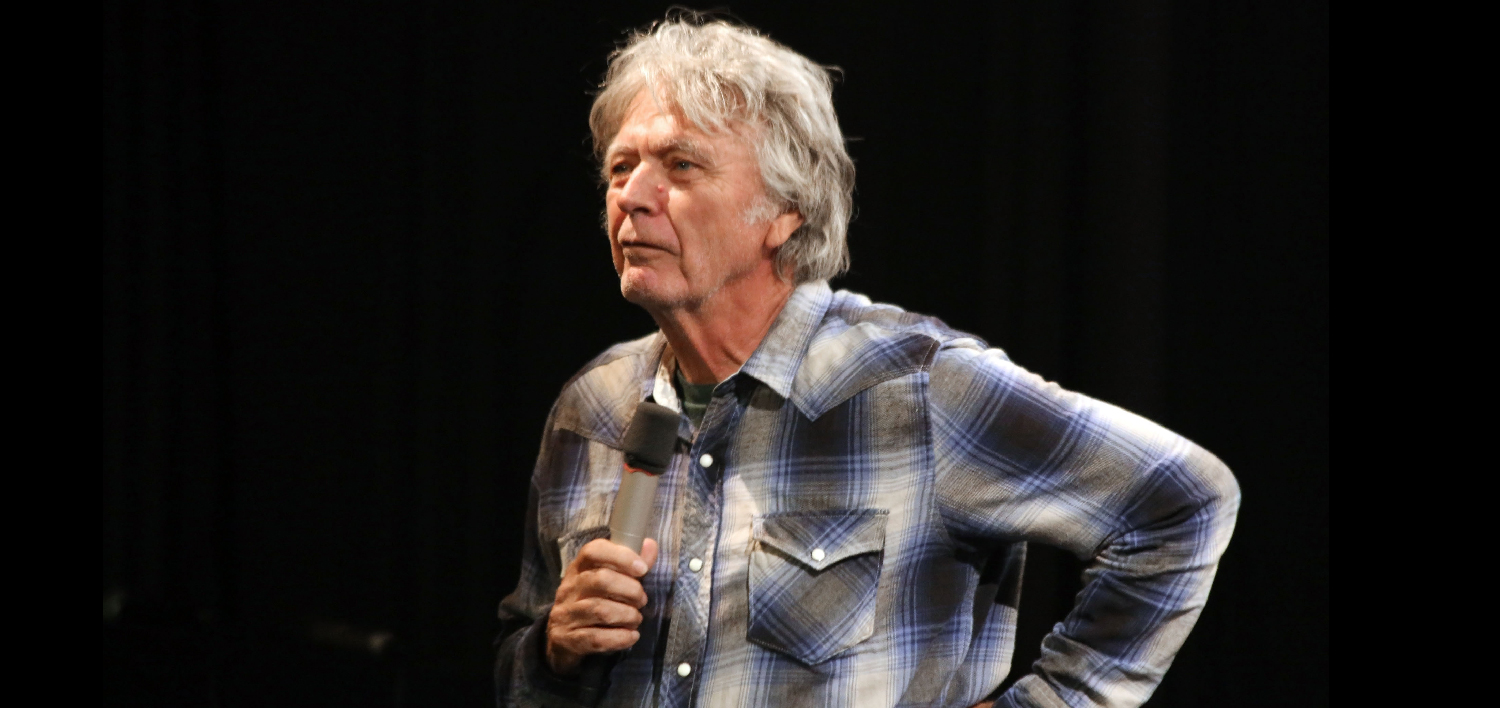

James Benning is an American experimental filmmaker whose work has had a major influence in both his home country and abroad, most notably in Austria, where the Austrian Film Museum has published books and released DVDs of his work. His friendship with, and influence on, Richard Linklater is showcased in Gabe Klinger’s documentary Double Play: James Benning and Richard Linklater and he is in Sydney for that and the miniature retrospective of his work, which begins Saturday 14 June at the Art Gallery of NSW. We sat down with him to talk film vs digital, social media and classes on ‘paying attention’.

So you have come to the Sydney Film Festival for a small retrospective of your work and it seems that even within those six works there is an incredible range – you have the one that the series is being anchored around, American Dreams (lost and found), which is so content-heavy and you’re not sure whether to interact with image or sound, which contrasts with Nightfall, which is purely meditative. Has there been some evolution in your perspective creatively in thinking about how to, not engage with the audience, but how to engage yourself content-wise?

Well American Dreams was made in ’84 and I think it’s really the beginning of the first film I made with text and image and that has text in different ways, through a diary and also in recorded text and music, so it’s an information overload film, really. It’s also, for me, a coming of age film, of my own coming of age, the years that Henry Aaron played baseball, from ’54 to ’75, was the time I came of age and I thought it was interesting to put those years in context of political actions that happened during that time and then within popular culture and music having a counterpoint of one man’s diary that’s from the same city as mine, that was the kind of confused young man that at times spoke for me and at others spoke against me because he contradicts himself quite a bit in his a diaries.

When I saw the film I went in sort of blind to it and I thought, at first, that the diary scrawl in American Dreams was your diary –

Yeah, well it’s a first person diary and if you know a little about me you know I’m from Milwaukee and so for me the diary acts as sort of my own diary and becomes my alter ego, in a sense. And then you become aware that this is a real person and a real diary and it’s not funny at all and it’s quite tragic by the end. It’s interesting because [Arthur] Bremer got out of prison about four years ago now. He’s the only would-be assassin of a presidential candidate that has ever gotten released, but he’s restricted to the state that he committed the crime in, Maryland, which is strange. He’s out of parole, so I guess he can’t leave his parole district. But he’s a very interesting young man, he was very confused and really wanted to become infamous.

Gabe talked to me a few days ago about your ability to just have one man, one camera, one set-up for a lot of your works. When you moved from film to digital – I believe your last film shot on film was RR – did you find that it made filmmaking easier or did the process lose some of its charm?

Well I wasn’t sure I’d like digital at all and now I wish I’d had it my whole life because I have complete autonomy with it as a filmmaker, I don’t need labs and I don’t need anybody. I can make films basically for free now once you have the equipment. Computers break and you need the hard drives but relatively it’s day and night with the cost. The equipment’s smaller and lighter, I don’t use a Nagra anymore, which was a very heavy tape recorder, now I use digital sound devices that are very small and do excellent work. I like the idea of post-production. With digital I have so much more control, with film you could never change contrast. The ability to change contrast allows you to make mediocre shots look well-shot during the magic hour. It still has a flatter look to it, it doesn’t have grain, which I don’t miss. Many people have a nostalgia for grain and miss that but I feel like the digital image is much more real because you never see anything with grain in it and the fetishing of grain is something that I get nervous about, although I like the look of film of course, it has a little deeper feel. I think if you play with the image and you know what light your camera likes, you can make images that certainly come close to being as film-like as possible and then the added control is so much greater.

Did you do much post on Nightfall?

Not much, I mean, that was shot with the lens set on automatic exposure, so it kind of gives you a fake sense of nightfall because the lens is opening up as it’s getting darker and once the lens is all the way open then you get the truth, well you don’t get the truth, you get what the lens, what the sensor can sense, when it gets that dark. But it somewhat simulates what you experience. I cleaned the sound a bit, here and there, but it’s pretty much just that shot, recorded and synced.

With all of your recent films being shot on digital and screened at festivals, there seems to be a difficulty in accessing many of your earlier works. Outside of the Filmmuseum in Vienna and their DVD series, a lot of your films are not readily available. Do you want them to feel like these contextual objects?

That’s because I’m afraid to rent them because they get destroyed. And people say, “We have good projection,” and I say “Do you have someone who maintains the projector?” or “Do you have a regular projectionist?” and they say “Well, we haven’t uses it in three years.” So I say “You’re gonna wreck the film” so I don’t rent them. I’m a little bit hesitant these days because it’s hard to make prints now. With digital files you can just send them out and once you send them out people copy them and there’s copies everywhere – no controlling it – I don’t care, it’s fine, sharing is caring.

(Laughs) I was reading an article Mark Peranson wrote for Cinema Scope where he interviewed you, he said that because of digital there was, he had this line – “let the retrospectives begin” – the ability to project digitally now allows festivals and audiences to rediscover your work in a more broad way.

I mean I never wanted my films on DVDs or anything but at this point projection is so bad that watching it on your computer is maybe a better experience…

…it’s a more intimate experience

Yeah and it’s really helped people know my work more. In a sense, the internet has made my work more well-known because people talk so much on the internet. So they create a demand for those things. Before I was way underrated but now I’m way overrated.

(Laughs) Well there’s now an ability to research and find information so quickly. Speaking of the internet, I want to ask you about your Twitter account. I think I only realised yesterday exactly what’s happening with it. Are you posting then deleting an image every day?

Yeah. I do that with Facebook too. In Facebook, though, it goes into your storage of photos. I mean, I could delete them but I just take them off the page. On Facebook, every few days I create a different sort of sketchbook of ideas. Sometimes they’re very playful and stupid and other times very serious and sometimes very political and sometimes about sex, you know. So I do kind of different themes. Whenever I have a few minutes, rather than watch TV now I play with that.

You play with social media. It is interesting that because you are doing one tweet and it’s an image as well, with caption, then deleting it – it’s kind of the perfect opposite to what people do on social media, a storage of wayward ideas and thoughts in permanence.

Well, that way people have to look when one happens or it might be gone.

There’s a moment to your posts as well. You’ve made your social media have a set time as well. I terms of your background, you’re a teacher of film now at CalArts and you were studying Mathematics at university. How do you approach film when you teach it to your students, considering the nature of the films you make?

I wouldn’t want to create more monsters so I don’t really teach my own work, although once I did a course on my films for a semester and people would like me to do that again but it’s a very difficult thing to do. It’s really hard work. I mainly have courses where I’m not really sure what I’m doing from day to day, and then I react to what the students bring in or what they’re talking about and then I might show them something the next week that relates to those ideas. So it’s more about me learning from them and I think we get such good students that it’s easier to do that at my school perhaps. But I don’t give any assignments, I have strange courses that are about deconstructing acting or are about going and paying attention. And the school, even though it’s becoming much more conservative over time, it’s still allowing me to teach the way I want to teach. Although they’re trying to force me to have a syllabus, and I can’t do that because I don’t know what I’m gonna do until I get there, which is a hard way of teaching but I take that method very seriously and I don’t want somebody telling me I have to have something preconceived.

I read this piece you wrote about teaching where you write about taking students to practice paying attention and you described five different students’ perspectives on what they saw. You said that experience was “one of the best films I’ve seen or heard”. How do you reconcile that with your notion that the “audience has no consideration” in your mind when you make your films?

Well, of course, if I’d ever got an audience I’d probably start to consider them, because of course if you are just making things and nobody pays attention to it, it might be brilliant but it still would be depressing. I’ve always thought of my work as setting up problems and then trying to find solutions, very much like you work as a mathematician, find an elegant solution, the elegant solution is generally the one that’s most direct and the simplest. Still that’s what I try to do with films and I hope than an audience will be interested. Lately people like to like my films, which makes me feel good.

Are you going to make any more films in the vein of Easy Rider?

I made a remake of Faces, so those two together I have showed at the Pompidou center in Paris together and maybe a few other places. Faces is the much more difficult of the two films but I think it’s much better, much more radical. It just uses and appropriates footage from the actual film and I like how simple it is, it’s purely about faces, I don’t know if you’ve seen it…

I haven’t actually, neither Cassavettes’ or yours

Well he does a lot of close ups in his film but it isn’t all faces so I thought that the film should be all faces. So I did a kind-of mathematcial analysis of screen time, how long everybody’s on screen and then I found a close-up of them from a scene and so if they’re in that scene, for ten minutes, I take that fifteen second close-up or three second close-up and lengthen it to the length of their screen times. You get these very slow movements that are very revealing of character and you really see the structure of Cassavettes’ film kind of in a different way.

One final question – in Double Play, you are watching Richard Linklater and his editor make Boyhood and the way that film plays with time relative to your own works. Have you seen Boyhood?

I haven’t. I’ve just seen what we saw at the time of its editing. What I was impressed with was how easy he was making these year jumps without making a real point of that articulation and I really like the way that would change. But then I also just saw little snippets of it and some of it I thought was a little bit, I don’t know, I was disappointed with some of the ways he was portraying things but I couldn’t tell from the film I saw. I really want to see it, if the narrative of it makes me not like it or makes me like it more it really isn’t important because I think it’s genius what he did.

It’s been the best thing I’ve seen at the festival. I guess in the opening hour it’s a little too reliant on its time-jump structure but as it moves towards the middle it becomes something brilliant. I was saying to Gabe that you could compare Boyhood and American Dreams through the usage of these popular cultural references, especially through music.

I saw a few places in the film that I thought was cliché about, you know, liberals and conservatives, and I thought those were a little too easy but that’s all I was seeing and it wasn’t in context, but I know I’m gonna like the overall film because I love what he did.

In context, those political scenes work, I think. In particular the scene with the conservative grandparents. Hopefully you get to see the film soon. Thanks for your time, it was great talking to you.

Thanks.

James Benning: An Outsider Visionary begins Saturday 14 June at Sydney Film Festival.