We have a tendency to mythologise the lost projects of great artists, without consideration for the possibility they could have been bad. Think Kubrick’s Napoleon or the Beach Boys’ version of Smile. In Jodorowsky’s Dune, Frank Pavich relishes the opportunity to expand this invisible canon. You leave the documentary believing that Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune is the greatest film you’ve never seen.1 There’s a sense that his unconsummated adaptation of the Frank Herbert sci-fi novel would have changed things.

Jodorowsky is an exemplary subject. He mugs for the camera, telling his story with ample theatrics and swirling gestures. He balances considerable panache against these compelling instances of treating the camera like a confidante, revealing his trade secrets with a whisper. The documentary’s opening segments move quickly through Jodorowsky’s time adapting theatre and fighting Mexican trade unions, acquainting us intimately with his philosophy. He’s an artist, through and through, without mind for compromise. We see brief moments of El Topo and The Holy Mountain—the films that made him—but they are not our focus. Neither is the novel, apparently. Jodorowsky claims to have never read it.

Instead, Pavich’s focus rests on the team Jodorowsky assembled to create Dune. Including H.R. Giger, Moebius, Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, and Salvadore Dali, Jodorowsky’s crew contained much of the twentieth century’s talent, at least where surrealism is concerned. It’s remarkable to hear these people talk so endearingly of him, and a shame so many died before the documentary was conceived. They tell of Jodorowsky rejecting the special effects coordinator of 2001: A Space Odyssey because he was a technician instead of an artist. We hear him persuade Pink Floyd to compose a score by yelling at them. We’re granted a feel for Jodorowsky’s magnetism (and luck) when he reminds us the 1970s were pre-Internet. Paris—in those days, he says—was something of an intersection. Mostly, he just runs into the people he’s pursuing. One by one he convinces them to upend their lives and pursue his masterpiece.

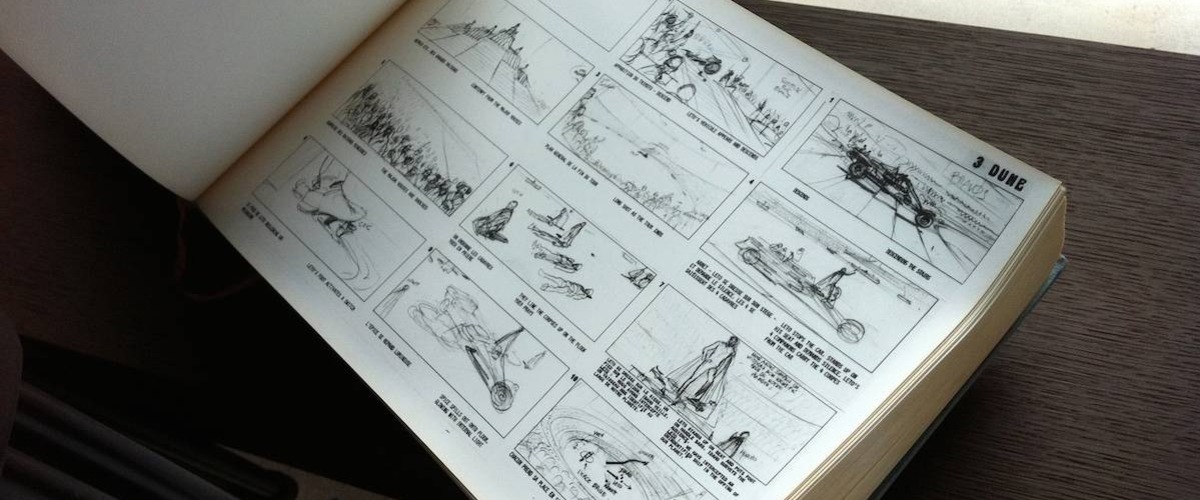

Structurally, the documentary is simple, composed of interviews, recordings, scans of storyboard designs, and brief animations. Pavich might not innovate within the medium, but it isn’t necessary. The subject compels us on its own, and there’s a sense that Jodorowsky’s vision would only be obscured by visual adulteration.2 I’m reminded of a scene in which Jodorowsky explains his then-willingness to die so that Dune would be made. Undoubtedly, Pavich could played this against scenes of mutilation in Jodoorwsky’s prior films, but he ignores such cheap theatrics, knowing it’s better just to let the camera run. Beyond Dune, the film also has much to critique in Hollywood. Jodorowsky and his producer both blame dealmakers for blocking the production—either because it was audacious, or unmarketable, though they’re convinced that’s untrue. Hollywood’s refusal to conceive of films beyond profit margins is among the documentary’s strongest claims, conveyed through the image of Jodorowsky losing his cool.

When Pavich does render Jodorowsky’s material on the screen, he does so with restraint. The storyboards and designs are crudely animated and, in that form, they’re able to evoke rather than prescribe, offering inexhaustible promise by drawing upon our imagination to fill in the blanks. It’s ironic then that Jodorowsky’s Dune was refused funding on the basis of its length. Jodorowsky’s Dune comes in at 88 minutes, an exemplar of efficient storytelling that conveys—in broad strokes anyway—some sense of his vision. Similarly, while the documentary empathises strongly with Jodorowsky, it still conveys some suggestion that his temperament almost assured the project’s failure. The comic book—film’s closest relative in terms of marrying image with word—becomes Jodorowsky’s preferred medium, and even though he finds form to recycle some concepts from Dune, we’re left with the unshakeable feeling that its most revolutionary dimensions are lost in translation.

In an early sequence, Jodorowsky outlines a plot point he changed in Dune. The hero Paul’s father had been castrated, so Paul was conceived through a drop of blood. Pavich places Jodorowsky’s project in parallel with this spiritual conception. Here, the film’s tragedy is most poignantly evoked by gesturing towards an alternate history of film in which Dune—rather that Star Wars—influences a generation. Pavich presents eerie parallels between frames of Dune’s storyboard—which Jodorowsky suspects was circulated around Hollywood—and the most memorable sequences of Star Wars, Masters of the Universe and Raiders of the Lost Ark. Meanwhile, Dan O’Bannon, Dune’s would-be effects guy, ended up writing Alien for Ridley Scott, taking Moebius and Giger along with him. As for Salvador Dali and Orson Welles… well, they just died. There’s much in this kind of analysis, tracing the genealogy of talent from its blood-source in Jodorowsky, and showing how his vision was contravened and absorbed by other projects.

In Jodorowsky’s Dune, Pavich transposes Jodorowsky’s ideology into documentary, combining the subject’s spiritualism and flair for self-help with gratifying allusions to cinematic history. It succeeds not by reflecting but by evoking the ideas he sought to convey. Just as Jodorowsky’s Dune was to end with the even distribution of Paul’s soul amongst all of humanity, Jodorowsky’s Dune concludes with a call to arms from the filmmaker himself. He tells the viewer to make art, and in making art to avoid compromise. In this message, he endears himself as both friend and mentor, human and divine. You will never see Dune, but you’ll feel it through this.

Around the Staff:

| Mei Chew | |

| Christian Byers | |

| Conor Bateman | |

| Felix Hubble |