As with all great films, the echoes of Tsai Ming Liang’s Stray Dogs resonate with you long after you leave the cinema. It is a perfectly realised, distilled-to-its-purest-essence poetic work of tremendous emotional power. Although it is Tsai’s first feature-length film shot on digital, it seems as if he is already an old master of the medium, the possibility for longer takes and the relative sharpness of the image well suited to his methods of representation. Having premiered almost a year ago in Venice, much great writing on Stray Dogs has already been completed,1 and here I will simply try to explain what the film does and why its impact on me was so great.

“Human billboard” Hsiao Kang (Lee Kang-sheng) is a living symbol of the absurd disparity in modern Asian cities of rapid development existing alongside abandonment and decay. By featuring a homeless man advertising homes, Tsai inverts the visual iconography of picketing to elevate Hsiao Kang’s act of holding a sign on a busy city street to an ironic act of anti-protest. He is the single father of two young children, son Yi-cheng and daughter Yi-chieh (played by the director’s own godchildren, Lee Kang-sheng’s nephew and niece). They live together on the margins of Taiwanese society, forging an existence comparable to the film’s titular stray dogs who occupy the same abandoned residence they take shelter in. They eat on the street, wash in public bathrooms and sleep huddled together on a single shared mattress. Three women appear in the film, one only in the first scene, one in the middle section, and one in the enigmatic final chapter. While all exhibiting maternal characteristics, it is ultimately ambiguous though not out of the question that they serve as iterations of the same character.2 In the end, their exact identity is irrelevant, with the narrative ambiguity forming part of Tsai’s strategy of paring-down of the elements of Stray Dogs to their essentials to liberate their representational capacity.

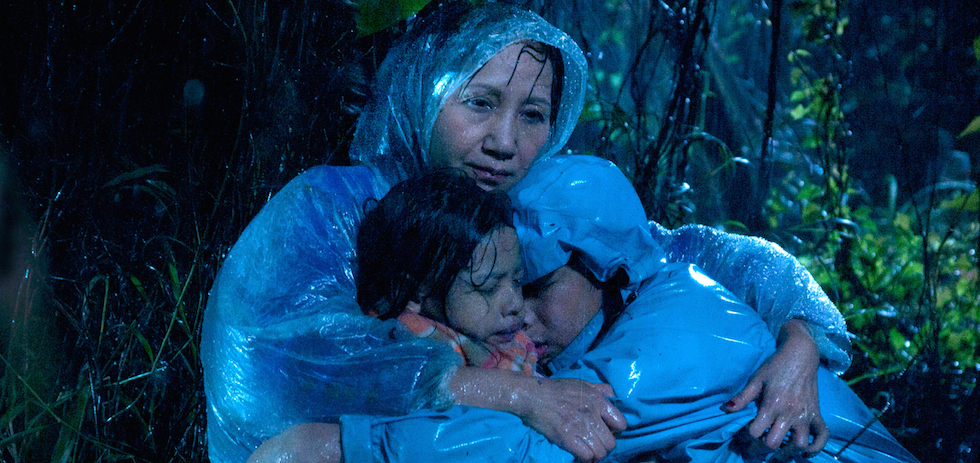

Tsai said in an interview that “the structure of the film has no beginning and no end.” Each shot is designed as a kind of structural unit representing an action of some sort completed by a character or characters. The spatial and temporal linearity or clarity relied upon by conventional narrative cinema is often disrupted by sharp cuts to new events and spaces, seemingly totally disconnected from those prior. For example, in a scene clearly taken from Charles Laughton’s 1955 expressionist masterpiece The Night of the Hunter (one of Tsai’s favourite films), Hsiao Kang attempts in the manner of Robert Mitchum to take the children away on a boat trip, but they are held back by the sudden appearance of the second woman (the mysterious supermarket employee played by Lu Yi-ching), who holds them firmly in her grasp in a tree as torrential rain pours and Hsiao Kang floats away from reach. After a fade to black, the next shot features the children suddenly reunited with their father and the introduction of the third and final woman, suddenly returning to the black and white paint-dripped bunker we have not seen since the film’s opening shot. No explanation for this abrupt change in space and time is given, but at this point none is really expected or required.

In other films that adopt a similarly experimental approach, the effect is that the emotional power of the film is dissolved entirely, the audience having become estranged from the action on screen. However, in my mind the great achievement of Stray Dogs is that the opposite is true, in that the emotional impact of the film is actively enhanced. The precise mix of elements that combine together to create this effect is difficult to pin down, but certainly owes in part to the power of Lee Kang-sheng’s face, a feature of all of Tsai’s films but perhaps never seen quite so expressively as here – in such crisp digital close-up and in shots of such long duration. I refer here in particular to the close-up of Hsiao Kang reciting Yue Fei’s A River Filled with Red as he stands with his placard and cries, the infamous cabbage-eating scene and the penultimate 14 minute close-up shot of him standing behind the third woman (played by Chen Shiang-chyi) looking ahead at something, crying and drinking small bottles of liquor one after another before he is eventually compelled to move forward and embrace her. These static shots of long duration perhaps find their closest counterpart in Tsai’s previous work in the austere tableaux of Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), but are here taken to even further, bolder, more hypnotic lengths.

The film’s most spectacularly beautiful shot is also its last, where it is revealed that what Hsiao Kang and the woman have been looking ahead at so intensely for the last 14 minutes is in fact the charcoal mural of a coastal landscape seen once before earlier on in the film.3 The woman leaves the room, the final shot eventually featuring only Hsiao Kang, shown for several minutes shot from behind swathed in dark blue light as he contemplates the mural in front. We the audience realise that, like Hsiao Kang, we too have been staring at a picture on a wall, moved by what we have seen. It is this shot which expands the scope of Stray Dogs infinitely beyond that which is represented on screen, holding a mirror up to our own experience.

Around the Staff:

| Brad Mariano | |

| Matilda Surtees | |

| Dominic Ellis | |

| Ivan Cerecina |