David Fincher is never content with the easy answer or the simple narrative. While traversing the idea of crime time and time again, with detectives, journalists, suspects and even potential intellectual property thieves, the roles characters appear to fulfil on the surface never fully encompass their true selves – there’s always something under the floorboards, and Fincher intends on ripping them apart to find the beating heart. With Gone Girl, it’s no different – a surface-level suburban whodunnit that spirals into a near-delirious look at the media circus, a fickle and bored public and the way in which we perceive ourselves, using marriage as a thematic conceit.

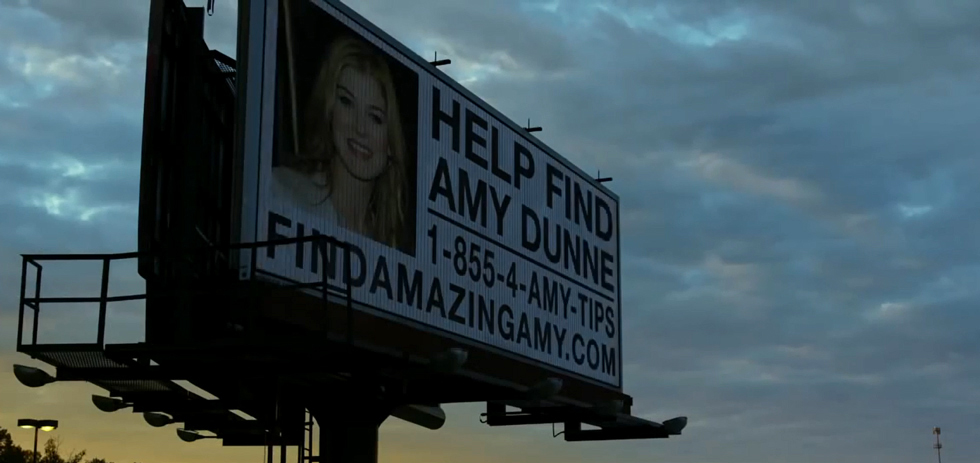

Like Dragon Tattoo, the plot of Fincher’s second bestseller adaptation in a row centres on a missing woman. In this case it’s not twenty years gone but a matter of days, as failed writer and barkeep Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) finds himself under suspicion when his wife Amy (Rosamund Pike) disappears under seemingly gruesome circumstances. Cue the bereaved yet parasitic in-laws, the rabid television talking heads and a police department whose investigation seems surprisingly simple, with a series of “clues” left by Amy as part of an anniversary treasure hunt for her husband allowing police to see just how fractured Nick’s marriage is. (When questioned about Amy he can’t recall her blood type, her hobbies, her friends.) Told in a parallel narrative, the present investigation is intercut with flashback sequences from Amy’s diary, the story we see in front of us always muddied by doubt.

Gone Girl, both book and film, relies upon a shifting narrative. Misdirection, red herrings and other hallmarks of the classical thriller are shredded to make way for an absurd, hilarious and shocking twist halfway through, and so, in turn, a lot of what the film does in its opening half is tread water. We move through the motions, the crime scene, the suspicion, the Law & Order episode, Fincher and screenwriter/novelist Gillian Flynn peppering dark humour throughout to keep things slightly off-kilter, though the film doesn’t entirely avoid having a touch of tedium about it.1 That said, once some of Nick’s faults reveal themselves both in past and present, things start to get very interesting, building up to the moment in which, tonally, everything we have seen so far becomes mere conjecture – substance emerging from the pulpy substance-less plot.

Affleck seems well cast as Nick Dunne, almost a caricature of a generic man and, though the shallowness of his character, as written, becomes apparent under further scrutiny, he makes for a reasonably affable protagonist, buoyed by the characters around him more so than his own character traits. There is of course the obvious meta-fictive implications of casting Affleck as a man hounded by the media, his face plastered on 24-hour news channels. In that same vein, Fincher has shown an aptitude for getting fantastic performances from surprising actors (think Timberlake in The Social Network), and here some his some stunt casting appears to be in full force. Tyler Perry, best known for his own outrageous comedies that mostly see him in drag, is transformed into a high-powered defense attorney who relishes being seen as the bad guy. “Blurred Lines” video star and model Emily Ratajkowski has a very effective turn as a minor character whose actions impact our perception of Nick considerably (not to mention the meta-commentary on the male gaze in light of the controversy surrounding that video). Casey Wilson, of the hilarious sitcom Happy Endings, appears theoretically against type in a thriller but firmly at home in bringing some serious laughs as a nosy neighbour. Neil Patrick Harris is underused and, while good, isn’t given enough space to move beyond the obvious darkly comic implications of his character – he feels less real than a convenient aside.

Then we get to Rosamund Pike, who seems to fully embody Amy to an uncomfortable degree. She is the clear standout by virtue of how much she is asked to do, both on-screen and in voiceover – as her diary provides much of the plot her intonation clearly shapes the perceptions of the audience.2 There is a coldness about her, too, even in the still image Nick stands in front of at the first press conference, her eyes seem like dark caverns, an echo of the camera-bear toy in The Game. As written by Flynn, Amy is not a typical female role in a crime narrative: despite being positioned as the victim, Pike never lets this render her character one-note. She wants to make sure the girl of the title is real, a flesh and blood incarnation of what has been lost.3

In a film dominated by women, where at one point Nick complains that he’s “so sick of being picked apart” by them, the best performances in the film come from actresses. Pike obviously stands out but Carrie Coon, as Nick’s twin sister Go, humanises Nick in an interesting way while remaining her own person, often as the only voice of reason. Kim Dickens as the lead police detective moves through so many incarnations with regards to her relationship with the viewer – vindictive, sympathetic, funny, threatening, ignorant, supremely intelligent that it is wholly impressive she remains a consistent character the entire runtime. She doesn’t have the throwaway lines about her own family and backstory like her partner (played by Almost Famous‘ Patrick Fugit, also really strong), but there is a subtlety in her dedication to discovery that makes her, arguably, the character we as an audience should side with most often.

While it works best in spurts rather than as a collective whole, the film does manage to fill out its 145-minute runtime by feeling like a novel, never rushed and perhaps giving a greater sense of tempered reality and weight to what is, fundamentally, a very silly story, which, not in spite but as a result of its ludicrousness, becomes a thrilling mess of plot and character. Unfortunately, while a large amount of the novel’s plot is replicated by Fincher, its visual restraint seems to run counter to the dark events of the narrative – we feel at an (oft-ironic) distance from the events in front of us, rather than in the scrum of the original text. That said, the moment of change and the ensuing twists have retained much of the novel’s brazenness, echoing recent South Korean thrillers in the way plot logic is jettisoned to craft a truly surprising visceral experience. Where those directors focus on hitting shocking plot points imbued with violence, Fincher and Flynn don’t quite commit to the same, circling back to vague thematic concerns with regards to relationships and consumption of image and, though it clearly comments on these in darkly comic fashion, it doesn’t entirely amount to something cohesive.

The film pairs its darkly comic sensibilities with a self-awareness that provides some easy laughs (Netflix gets name-checked, much like Natalie Portman in The Social Network) and aims to transcend the pulpy, oft-ludicrous plot. In that vein it is perhaps only successful half the time, as the film’s distance from events, mostly as a result of odd editing decisions, renders the truly dark scenes self-aware to the point where it feels more exercise than execution. The idea of the screen and television, though, is quite biting, Missi Pyle chews scenery as she relishes the opportunity to play a Nancy Grace stand-in on a cable news channel and Fincher cleverly uses a recurring image of a certain television eventually losing its signal to represent this idea of public perception as lifeblood. At times this does feel a little pat, for example when Nick delivers a speech at the vigil for his wife, after someone in the crowd reveals a secret the entire populus decides to turn on him and swamp him, the instantaneous shift a tad obvious in humorous intent.

The advertising campaign for the film is nothing if not clever misdirection, with Fincher showing he’s willing to play wildly with tone but within and without the film itself. In fact, he negotiated in his contract so that a certain aspect of the film from “reel four” onwards would never be used in promotional material. He seems to be aware of the Psycho effect; while Hitchcock could buy up and pulp as many copies of Robert Bloch’s novel he could get his hands on, here Fincher is grappling with a multi-million-copy-selling bestseller and one hell of a plot twist. 4

Unlike most of Fincher’s work, a lot of what plagued the film were issues of an aesthetic nature. The editing of the film tended to frustrate rather than streamline narrative. Though there is a clear intention to create doubt in the perspectives we see, having each sequences quickly fade to black felt jarring, the suddenness of the diary entries feeling less like an engaging accompaniment to the present time narrative than an interruption. The fact that the drive of the narrative is Nick’s perspective also shows the film too eagerly setting him up as a sympathetic figure, of sorts, by structural alignment. There are some good jump-cuts, the one that seems most apparent is the juxtaposition of Nick and Amy kissing and Nick having his mouth swabbed by police.

In addition to this, Fincher’s visual sensibilities appear somewhat restrained throughout Gone Girl. Though the opening scenes feature an uncharacteristically bright and sunny sky, perhaps Fincher’s attempt to satirise the suburban ideal, it lacks a gripping grounding in a visual location. Where in Dragon Tattoo and The Social Network places feel fully-formed, here exterior locations don’t stand out visually – the lake house’s exterior lacking impact, the woodshed lacking the requisite menace – this resulting normalcy not really enough to craft a cogent visual point about suburbia. Where Flynn’s novelistic North Carthage feels more run-down throughout (with abandoned homes a recurring feature), here this idea is only present in the opening montage and the only sense of decrepitude we get is in the abandoned mall. Jeff Cronenweth’s polished cinematography seems too clean and, though this definitely allows for readings of the narrative as allegory, all within a fishbowl (of sorts), it does tend to place the viewer at an arm’s length from engagement.

The score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, usually one of the strong points in Fincher’s more recent work, actually stands stronger outside of the film that within it, it’s a haunting work that ebbs and flows gently, a play on placidity. Unlike their work on The Social Network, which feels like the pulsing heartbeat of the film, or even Dragon Tattoo, which is much more subtle but often very affecting in select scenes, here their music is mostly absent from the entire first section of the film, only soaring in when twists and turns reveal themselves; their music feels inessential, an afterthought, even. In terms of songs themselves, where Fincher appropriated popular culture in his last two features (“Baby You’re a Rich Man” in The Social Network, “Immigrant Song” in Dragon Tattoo), here the only noticeable co-opting is a sly use of Blue Öyster Cult’s “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” as Nick drives his father back from the police station early in the film.

Despite all of this though, it’s worth noting that Gone Girl is a crime film crafted with more skill than most contemporary offerings. Its narrative absurdity makes for compelling viewing by virtue of its strangeness.5 While in theory much of the plot embodies a sense of playfulness, the film does feel a little cold, lacking the energy and instant hook of so many of his earlier films. Perhaps paradoxically Gone Girl takes itself too seriously while it lambasts the idea of self-aware construction of identity. It’s wary of its sense of humour but that makes the joke feel a little stale. The final scene of the film, instead of using the cutting final lines of the novel, plays it a little more nuanced, calling back to the beginning as if to remind the viewer of theme and narrative construction rather than the deranged sequences that have led to that end result. Fincher’s adaptation is strong and engaging, and one of his most audacious mergers of tone yet, but it’s only intermittently searing.

Around the Staff

| Felix Hubble | |

| Peter Walsh | |

| Jess Ellicott | |

| Virat Nehru | |

| Dominic Ellis | |

| Saro Lusty-Cavallari | |

| Imogen Gardam | |

| James Hennessy | |

| Dominic Barlow | |

| Isobel Yeap |