Beats of the Antonov in itself is a title that echoes the intersections of joy and pain that frame hajooj kuka’s documentary. The ‘Antonov’ refers to the planes employed by Omar Al-Bashir to bomb and attack those in the Blue Nile and Nuba regions of Sudan, while the ‘beats’ in question have more duality to them. There’s the more literal sound of the bombs make, but there’s also the sound of the drums and the songs that are so integral the resistance and perseverance of the people who face and fear this on a daily basis. kuka’s piece is a study of humans in the Blue Nile and Nuba region; an intimate examination of every facet that feeds into and defines this identity – from the war, music, culture and society – and what threatens it.

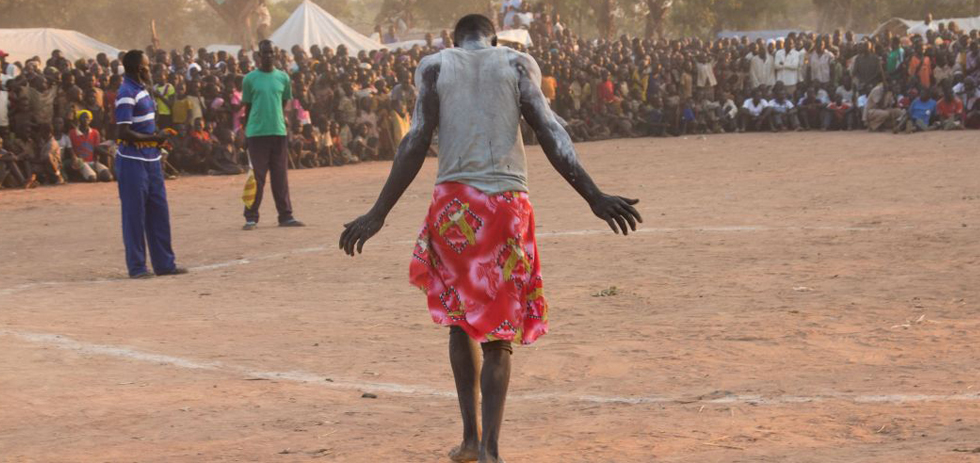

Tangible loss permeates kuka’s Sudan. Many of the people in Beats of the Antonov have lost their family, had their homes razed to the ground, or are constantly fighting to keep their livelihood; but the they’re singing and playing their songs throughout all of this. From the opening minutes of Beats of the Antonov, it’s markedly clear what the film isn’t going to be. Sudan and its people aren’t portrayed as sad, isolated victims and hajooj kuka takes no time in making this clear. It’s joyous, it’s self-celebratory and from the start there’s a genuine engagement with the people within the documentary. At the beginning, kuka’s main focus is an ethnomusicological survey of Sudan: their songs, the culture they emerge from, and the resilience and strength they give to the people who sing them.

“This war changes a lot of things” sounds like an understatement when it’s uttered towards the start of the film, but by the end the tone in which its said makes perfect sense. Obviously there’s a huge fallout from the violent conflict, however, throughout Beats of the Antonov, there’s a recurring focus on Sudanese identity as paramount. The conflict isn’t viewed as something that serves as a solely physical danger to Sudan; but something broader. One of the inhabitants of the Blue Nile tell kuka “I want to live a normal life” and a fairly substantial part of the documentary deals precisely with this existential dilemma. The idea of happiness, evinced through images of a “the real Sudan” – a place of music, culture and people with “no differences, no barriers” – is at the core of Beats of the Antonov, rather than the violence and geopolitics that makes this as hard to achieve as it is.

One of the recurrently refreshing features of kuka’s documentary is the refusal to romanticise, idealise or victimise Sudan and its people. One of the most fascinating and inspiring scenes comes in the look at “Girls Music” in the country, specifically focusing on the Blue Nile region. Cutting through several different songs, kuka traces an oral and musical celebration of femininity in Sudan as a group of women sing together in ecstatic celebration of themselves. “Everyone has the right to pick up a drum” one of them tells the documentarian, standing in defiance of the hegemonic Islamic Arabic influence in Sudan – epitomised in the Khartoum regime -, rather than the Nubian people calling for their own identity throughout the documentary.

Again, this isn’t a piece that looks an idealised, objectified Sudan, and this is double-sided. It is constantly nuanced, with every scene of musical transcendence matched up with those of the painful reality faced by many Sudanese. Not long after the women are shown singing together, another scene shows a man fatally shot on camera and carried out of a conflict by two fellow soldiers.In another harrowing scene, a man and his wife calmly walking through the ruins of their house, recounting how the Khartoum regime and violence has impeded their way of life. This pain is carefully documented by kuka, in a way that neither fetishises or delegitimises it, but recognises it as part of a broad spectrum of the Sudanese experience; deeply complex, nuanced and multi-faceted, tragic and celebratory.

Skin colour in Sudan is a recurring issue cited throughout the documentary as a frequent point of division within the country with comparisons drawn between black experience in the Sudan and that of America. In one scene, a singer, Sarah Mohamed Abunama-Elgadi reflects in her statement “we all hate ourselves” before raising the fact that “the idea that black is beautiful has not reached us yet”. In a poignant rhetorical question that lingers in the air for the rest of the film, she asks: “why has it not reached us yet?”. She continues by raising the most perpetual and constant imperative that isn’t articulated as directly until the end of the film: “if we don’t answer the question of the Sudanese identity war will continue”. Beats of the Antonov isn’t simply a work that documents or studies Sudan. kuka’s masterpiece is instead a running dialogue and self-examination of Sudan in the 21st century.