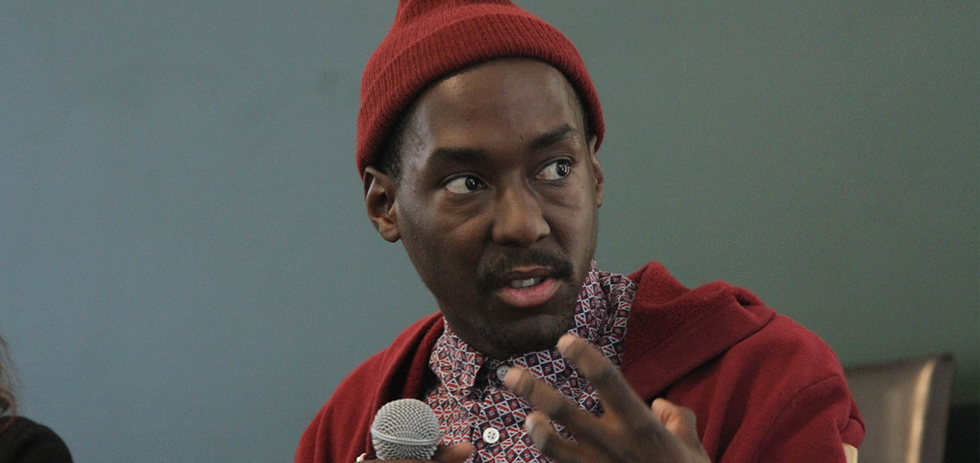

In Necktie Youth, Sibs Shongwe-La Mer gives audiences a different side of Johannesburg, South Africa. In a film that follows a hedonistic rampage through the city, the director seeks to expand the ways in which the city is perceived abroad, revealing a more complex and diverse society than most filmmakers on the past have portrayed. We caught up with Shongwe-La Mer at Sydney Film Festival to discuss the success of the film and how he’s been perceived as a director.

Yeah, so to start things off I was thinking about the film being this kind of ‘sex and drugs’ drama in Johannesburg, I was wondering what stories inspired what comes off as such a personal film?

Well my girlfriend committed suicide when I was 15, so that kind of was the jumping point. So I kind of made Necktie Youth in memorial to her.

Did you begin work on it soon after?

Yeah… like two days after she died.

Was that kind of a long process to get it made from there… from what you originally envisioned –

Well, I’m 23 so it’s been… long.

How did you find getting a film made in South Africa as a very young filmmaker?

Tough. Yeah, tough. It’s really hard to make a movie when you haven’t been to film school and no one knows who you are. So it’s like “can I have a million dollars?” “No. …no.”

Yeah, I can imagine. I feel with that opening of Necktie Youth, it’s very dramatic, powerful and confronting as a way to open the film – and I was curious as, considering the funding issues already, whether you had to show something like that to the producers and ask for funding or?

Well, it was easier because we had the money when we shot the scene, so the producers were a little more… understanding.

I guess this whole 8 year period, with the original idea, to the eventual release of the film. That process from not having the money at all, to the film showing at festivals all around the world?

Well I wrote like… 9 scripts? Like “kids needs more hugs” I just wrote like… different versions, and I’d pitch them and they’d be like “No, you’re a child… shut up – go to film school.”

But you didn’t, right?

No (laughs)

I was curious, watching Necktie Youth, it doesn’t seem to take much inspiration from South African film… it feels a lot more inspired from international films?

Yeah, I don’t watch South African cinema because it doesn’t reflect the society that I’m used or the society that I grew up in… so every African selection, I don’t watch.

I found that what was one of the most interesting parts of Necktie Youth was that it had this image of South African youth which is was quite different to a lot of the perceptions that Western countries have been given of South Africa. Especially considering the biggest international depiction of Johannesburg in recent years was District 9 –

Which is where I wanted to depart from. In the sense of being like… I didn’t want to make a movie about the typical picture of Africa; of a whole bunch of shit. I wanted to make a film that showed I was never raised in the whole like “oh, give us two dollars”, you know, I was from the other side of Africa…

As in?

Rich. So, you know, it never made sense to me to see stuff like that and those kind of films… all of those films never made any sense.

I thought one of the main things confronting the figures in the film wasn’t ever economic – it was more boredom, apathy –

Exactly, it’s an existentialist film. It’s post-apartheid. It’s more about this generation of kids who are still struggling… but with the next phase. They’re trying to find happiness, they’re trying to find personal joy, more so than your typical apartheid struggles.

Do you feel that the apartheid struggles have created a very unique kind of a social landscape?

Yeah, I mean you can’t depart from it and its very much a part of South Africa’s consciousness. But I think the new generation is looking for a new freedom… which is more of an existential freedom.

I find that throughout, Necktie Youth, a lot of it feels inspired and shares a lot in common with a lot of Western coming-of-age dramas, and a lot to reviewers that have compared it to films like –

Kids.

Yeah, that’s been one of the bigger comparisons that people seem to keep making.

(groans) Um… Larry Clark is cool.

He’s got something screening at the festival at moment…

Seriously? Is he here?

I don’t think so, no.

Damnit. I mean, though, Kids was like a molotov cocktail for me when I was young. I just thought it was the raddest fucking thing I’d ever seen, and sort of made me want to make movies. So Necktie Youth is always going to be compared to Kids.

Do you think that’s an unfair comparison?

I like to think it’s original.

I thought it was a bit of a cop-out to simply call the film a “South African Kids” –

Dazed – (laughs) – that’s the article, yeah. No, I mean, I think it’s great on one level. If I can be compared to Larry Clark…

I can headline this “an Interview with South Africa’s Larry Clark” –

(Laughs) no, no, no – don’t do it. Title it “it’s not Kids”

(laughs) it’s “It’s Not Kids – The Story of Necktie Youth”

“I watched this movie… It’s not like Larry Clark”. Yeah, I don’t want to headline it.

I’m sure it’ll just be called “An Interview with…”. Anyway, now that you’re in Sydney with the film – having received great reception around the world – I’m curious as to what you’re doing next.

Oh…. you’re asking me about my ‘next project’? (laughs) I signed with LBI, which is Leonardo DiCaprio’s label and WME, and Roadshow… Steve McQueen.

So you’ve got quite a few lined up?

I’ve got reps… Next project? Man… they just send me scripts. So I don’t know. I really don’t know. I’m reading Mudbound at the moment. It’s an adaptation of something set in Mississippi, that’s all I’m going to say. I’m writing two scripts. The first one is about a bunch of kids leaving South Africa for Brazil in search of ‘the hedonistic nirvana’ and they get up in the drug trade – who wouldn’t? – and then they end up in a Brazilian Prison in Sao Paolo.

That’s a decline…

So yeah, feel good movie of the year. Another Necktie Youth (laughs)

I guess at the centre of all this, I was just quite interested in how this all came together in the end – it’s quite a cleanly put together film… but you didn’t have long to shoot it?

We had fourteen days to shoot it, so…

Was there a reason you shot it in black and white?

Yeah, you know, just a romantic representation of Africa.

Do you feel there’s much missing?

Lots missing. I mean, if I had more time I would have shot it better. But I think I kind of shot it well.

I guess that’s kind of everything. Thanks so much.

Thank you.