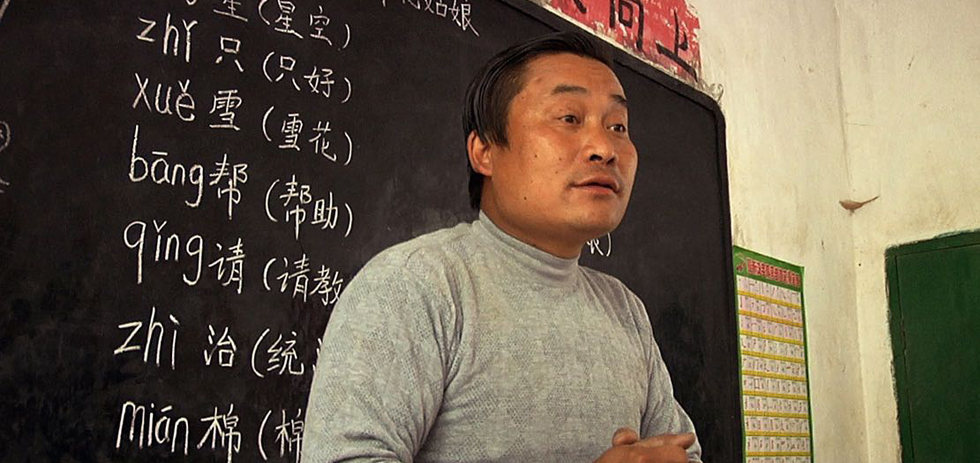

In the opening minutes of On the Rim of the Sky, Shen Qijun announces the impressive fact that he has served as the sole teacher at his school for 27 years – since 1982. Before 2008, Gulu Village – where Qijun resides and where Xu Hongjie’s documentary finds itself. Gulu was almost completely isolated from the rest of the Sichuan province and the title of the film serves as a fairly literal indicator of the reason why. Qijun’s school in Gulu is deep within the mountains of the province, perched in hermitude away from the perils and pleasures of modern society. Hongjie’s film navigates Gulu’s collision course with the rest of Sichuan alongside how Qijun himself deals with such a dramatic shift in his way of life.

Xu Hongjie’s ‘first-contact’ tale is one of two teachers: the instinctual Qijun and the younger, university-educated Bao Tangtao, who comes to Gulu Village in the wake of the 2008 Earthquake in the province. It doesn’t take long for the factors that create a dichotomy between the two teachers to become clear. Qijun is reluctant to let Tangtao take over as much of the school as the latter wants to, and Tangtao is determined to make dramatic changes. At the center of their conflict is a palpably evident clash of two cultures: the city and the country.

Neither figure is treated unfairly by Xu Hongjie. That said, his film doesn’t portray them in an exclusive positive light either. Shen Qijun is controlling and his refusal to relinquish his power in the village reflects broader issues that become clearer throughout the documentary. For 27 years, Qijun is unchallenged, he’s held up as the most knowledgeable villager (with the highest education in the village since 1982), as well as a respected shaman. In the arrival of Bao Tangtao, this is all compromised. That said, even while Tangtao brings with him electricity and various advancements for the village, his intentions are always challenged; both in subtle and more overt ways by the director. His time in Gulu isn’t permanent, while Qijun’s is, and in his arrival Tangtao gives himself to the village an impermanent figure. Sometimes, Hongjie goes as far as to frame him as a tourist, a wealthy city-dweller who simply wants to see how the villagers live before leaving again.

Bao is from an highly educated background, and it’s evident from the second he steps on screen just how much he romanticises his own position in the town. “Gulu is a small, graceful utopia”, he expounds, before quoting the famous Oscar Wilde line “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars”. It’s no surprise when – in one scene when discussing his taste in literature and his politics – he reveals a deep admiration for Che Guevera and Jack Kerouac.

Meanwhile, Shen often talks about his “private issue”, which is the fact that he is a substitute teacher, without a degree – wherein having such would have put him in a place of far greater security. He often reflects on how close he was to having one, various chances of him receiving qualifications – at one stage discussing a friend that had alleged he would give Shen the title he needed before the friend suddenly lost their own title. His reflections are punctuated by a constant misfortune that prompts the viewer to ask: is Shen telling the truth in his confessionals? Is he genuinely a deeply unlucky character, or, instead, has is he in the position of having spent the last several decades in a position where such statements could go unchallenged. It’s never delved into by the director, but it’s something that lingers in the air throughout the film’s duration.

The film is shot beautifully, enamoured in the mist, greenery and the endless winding mountains that define Gulu. In the few shots of the city, and even less isolated villages throughout, Gulu is distinguished as markedly lost in time. It’s an increasingly rare subject for a documentary, and for Xu Hongjie to have gained access to such a remarkable place – alongside an equally astounding tale between two individuals – the director has stumbled upon a genuine uniqueness in its subjects.

The literal translation of the film’s Chinese title – “it will be better tomorrow” – exemplifies what sits at the core of the film; a society moving out of the past and into the future. For Shen, tomorrow is something that is encroaching on his peaceful and stable way of life, while for Bao the same word is exciting and inspiring. It’s a contrast that lasts a lifetime, and by the end of On the Rim of the Sky it becomes clear that Shen is the victim of a shifting sociopolitical landscape. China’s teleology is moving away from the folk hero, towards the educated everyman and Hongjie’s film is a case study of this movement. The isolated school is closed by the end of the film, despite the efforts of both men, it finds itself superseded by less inaccessible counterparts.

In the final scene of the film, occurring almost two years after the last encounter between Bao and Shen, the latter remains while the brief presence of the former has long ended. Hongjie asks Shen – who has just stated: “I haven’t been to the school this year” after it has closed. Asking “won’t you visit again?” Shen’s answer is a short “no” and when Hongjie questions, Shen’s slightly less brief response also marks the final line in the film. A poignant, and reflective “it would make me sad.” When Xu Hongjie initially went to Gulu Village to make the film that ended up On the Rim of the Sky, it’s unlikely the director was aware he was filming the end of an era. With Shen’s final words, however, it’s clear that Hongjie’s piece is an invaluable document.

Around the Staff