Given the cult of food-related reality television and this particular film’s programming as part of the Gourmet Cinema program, it’s easy to see what kind of niche Sergio Herman: FUCKING PERFECT is expected to occupy. Any promotional façade you may see is best ignored. This is not Masterchef or Kitchen Nightmares. This is not just a food film for food lovers. This is a film for film lovers, shot on 16mm film stock, with an aesthetic trading more in chiaroscuro than kitsch; a visually expressive, cinéma vérité character study, and an exposé (and exponent) of obsession and perfection.

Sergio Herman is a fanatic, a single-minded, obsessive perfectionist, determined, as the title suggests, to run a fucking perfect restaurant. After 25 years, however, Herman decides it is time for Oud Sluis, his 3 Michelin star restaurant, to close its doors. The main body of the film is spent watching Herman try to balance spending more time with his family with running his other restaurant and opening another in a converted church. In all this, we come to know Herman as a committed, conflicted and restless man, struggling with life in the kitchen and life at home, appearing most at ease in the workplace surrounded by his family. He shares self-aware laughs with his workers, mocking the kind of aggression trademarked by Gordon Ramsay. That said, he is a tremendously passionate man and a fascinating man, stuck between the opposite poles of passion and will.

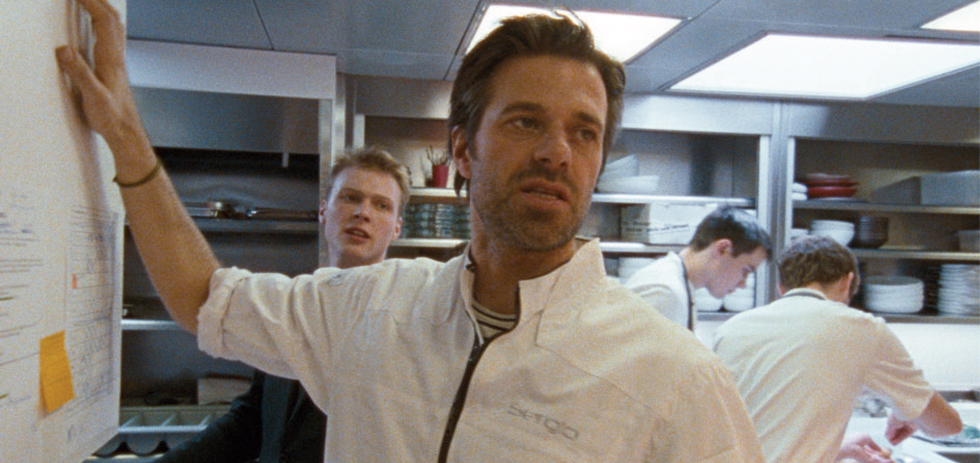

The defining characteristic of the film, distinguishing it particularly from food television, is that it is primarily visually articulate. W.J.A Kluijfhout endeavours to avoid the cliches of modern documentary filmmaking, less interested in conversation, interview and subtitles, more intent on creating a pictorial narrative. Throughout the film, Herman is often framed in half light, as a kind of godlike figure, his key interview and the only ‘talking head’ in the film, shot in complete darkness but for a single cold light illuminating his eyes, nose, mouth and high cheekbones. In this, he is stripped of all decorations and distractions, a simple man stuck in a void. Within this dark image which becomes the framing device for the whole film, Herman shares his deep-seated existential doubts and equally strident ambitions, as they intertwine into one. As in a sequence in which Herman, stalking about in diffused white light, surveying the to be converted church, the film’s stance on Herman is an unusual one, constantly foregrounding its apparent sympathetic bias and undercutting potential inclinations towards hagiography.

Kluijfhout’s rendering of Herman’s journey is particularly impressive in her use of Oud Sluis as representative of Herman’s inner state. Throughout the early parts of the film, the insanity of the kitchen defines Herman’s life. In a later scene at home with his family, Kluijfhout cuts the image of the empty Oud Sluis over the top, showing Herman’s innate capacity for work going unfulfilled. Later still, when Herman is struggling with the other restaurants and his necessarily shifting standards, Herman returns to Oud Sluis which his brother has reopened as a modest eatery to find three people pottering about his formerly hectic kitchen and making depressing looking salmon on toast, before cutting to the glass door bearing Herman’s former Michelin certification. In articulating Herman’s inner state with images of his external world, Kluijfhout makes full and consistent use of the visual capacity of the documentary form.

In addition to her fine narrative instincts, Kluijfhout displays a control of lighting and colour that even many contemporary fiction directors, let alone documentarians, don’t seem to bother with. The balanced colour palettes throughout are so precise as to doubt that Herman dressed himself and more impressively, given that it’s a rogue element in a majority of documentary filmmaking, the lighting here is perfect. The consistent balance of warm and cold colour temperatures, on both a thematic and a purely aesthetic basis, is as good as any documentary I’ve seen. The dim warm diffusion of Herman’s restaurant floors, swamped as they are with demanding, intimidating customers, have a dull hellish glow to them and the hard cold lights of the kitchen are the perfect visualisation of the intense, aggressive environment, figures and blocks of hard white light, bursting overexposed out of nowhere like white rhinos.

Particularly, the use of warm and cold colour temperatures as thematic elements, warm as the passions, cold as will and logic, finds its payoff in Herman’s aforementioned ‘talking head’. Within this frame, it eventually becomes apparent that what we are seeing takes place in a car as Herman drives home from work, giving the shot a diegetic grounding to go with its hitherto otherworldly aesthetic beauty. The shot pays off in the film’s final moments, as Herman admits his refusal to relent in his pursuit of perfection, saying he still wants to run another restaurant, as he turns his head for the first time and a hot warm light pierces the cold, subtly but clearly, as his passions triumph over his will.

For me, this is possibly, probably the film of the festival. Given what it suggested it might have been, from the first moments, it is clear we are in an altogether different cinematic milieu, shadows, film grain and impeccable, impressionistic composition bolstering a documentary voice that is all its own.