As a result of being a last-minute addition to the Sydney Film Festival program, and lacking the monumental hype that has followed his controversial Going Clear, Alex Gibney’s latest documentary, Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine, is easily overlooked. In the wake of the widely-derided Ashton Kutcher-starring biopic Jobs and in the lead-up to the much-anticipated Sorkin-penned steve jobs, the life and times of the Apple co-founder is a narrative on the verge of overexposure. Gibney’s film, though, acts as something of a corrective, focused not only on a biographical account of Jobs, but also the way in which big business and consumers at large engaged with the mythic personal narrative he fostered. This multifaceted approach lacks the laser focus of Going Clear and the energy of his James Brown documentary, Mr. Dynamite, yet of the three films he has screening at the festival, The Man in the Machine might actually be the best of them; it’s a consistently rewarding viewing experience that probes and queries rather than asserting any particular truth.

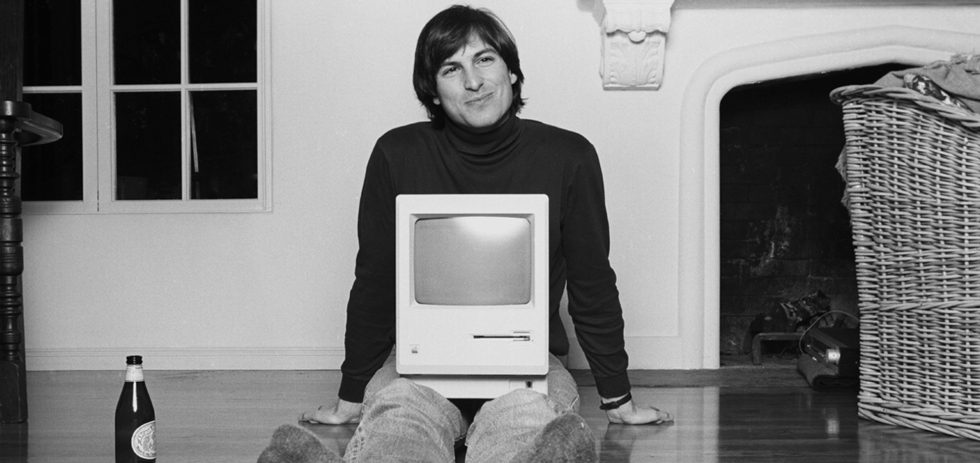

The documentary is borne from genuine curiosity rather than malice; Gibney’s opening narration explaining his personal confusion at the mass global outpouring of grief after Jobs’ death in 2011. What follows is the expected biographical approach but it’s rendered only in snapshots, quickly moving through Jobs’ childhood (which it circles back to at a later point, and for good reason) to get to his work at Atari and then in founding Apple. There’s a quasi-The Social Network approach that Gibney takes in telling these earlier years, Jobs and his Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak are affable characters with some extraordinary imaginations, but even here the competitive streak that emerges as a sense of superiority in Jobs is crystal clear, an anecdote about him significantly underpaying Wozniak (and lying to him about that payment) for work at Atari initially comes off a touch heavy-handed, yet when the documentary moves into Apple’s corporate greed later in the film these earlier moments gain a stronger sense of relevancy.1

Interestingly, an aspect of Jobs’ character not often explored except as ephemeral asides regarding his cancer treatment, is in his sense of spirituality and search for enlightenment. Gibney spends a lot of time in the film dealing with Jobs’ philosophical ideas and his inability to fully grapple with the idea of enlightenment as a result of his ego. To further the central importance of this idea to both the film and Jobs’ life as a whole, Gibney occasionally intercuts footage of a zen shrine in Japan, shot by cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki, the first insertion of which is a brilliant piece of editing that marries the screen of a computer with this space.

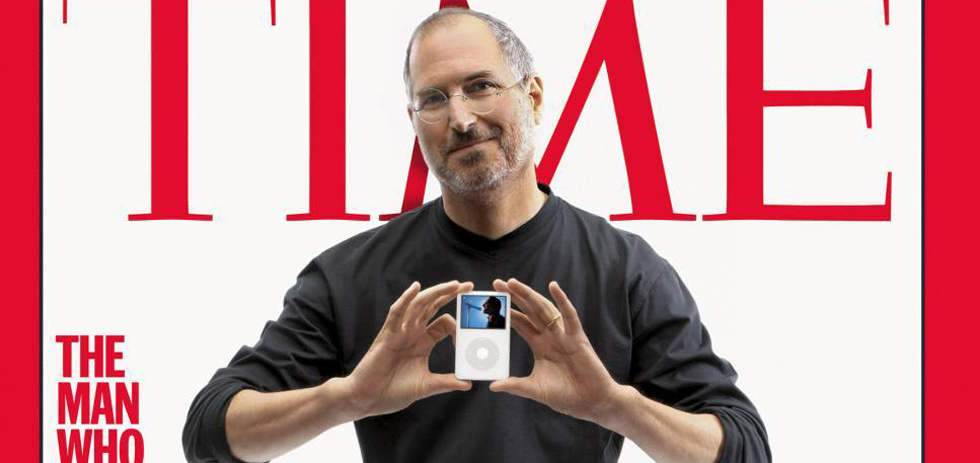

Gibney, whose defining style might just be a particular affinity for editing archival footage, seems to be experimenting with form within a somewhat conventional episodic narrative structure. For instance, he includes shots from cameras mounted to the front of trucks to introduce cities, one anecdote about Jobs’ attempts at enlightenment are animated (by Nick Gibney, presumably related to Alex), and almost the entire soundtrack is comprised of songs by Bob Dylan, whose lyrics Jobs was a known acolyte of. The interplay with music and image is also what elevates Gibney’s section of the film centred around advertising. He plays the start of the music video for Feist’s “1234”, triggering instant nostalgia for the Apple iPod mini commercials, then shows those commercials; he plays one of the greatest advertisements of all time, Ridley Scott’s “1984” ad for Apple, then plays behind the scenes footage of that ad’s making with his voiceover describing how Apple has in fact become the Big Brother (read: IBM) of today, all impressively stitched together by editor Michael J. Palmer.

There’s a section of the film packed with information about illegal financial activity within Apple and other tech companies that suddenly pieces together a startlingly different portrait of the company than the one its ingenious marketing and Jobs himself have crafted, and it calls to mind many of Gibney’s earlier documentaries adapted from books, which, for this section of the film, it actually is; Peter Elkind re-emerges in Gibney’s filmic wheelhouse, a producer on this film and the author of the fantastic book on which Gibney’s Oscar-nominated Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room is based, we move through some of the accusations he leveled at Steve Jobs in 2008 in his piece for Fortune Magazine. This then takes us on dual tangents, one which focuses on some of the more well-known Apple news stories – Foxconn worker suicides, Irish tax havens – and another which looks at Jobs’ aversion to any press he himself can’t control, with Gibney interviewing writers and editors at the New York Times, Fortune and Gizmodo, which published a massive scoop in 2013 regarding the newest iPhone, only to have writer Jason Chen’s house searched by a police taskforce seeming on the orders of Jobs himself.2

Whenever Gibney deals with consumer engagement, The Man in the Machine becomes really compelling, the writer for the New York Times featured in the film blankly states “it’s a company that makes phones” and that perhaps is the key focal point of the film, not only of the power of advertising (something I hope Gibney makes a whole film about), but that the myth of Jobs masked the very real unethical corporate activity at Apple but also the willful ignorance of consumers. In arguably Gibney’s best film, the underseen ESPN-produced Catching Hell, he turns his lens to not only one specific event but also fanaticism in sport and thereafter the oddity of the general population. Whilst he doesn’t usually mine that subject –early Errol Morris has it pretty much on lock – it makes for a fascinating experience, having a documentary broadly point out some of the collective flaws in its own audience. Here the idea that iPhone technology is an isolating tool rather than collective, encouraged by the “personal computer” advertising strategy Apple has used since the ’80s, sees the brand of Apple inherently protected by the consumers who see themselves in its products.3 Thus, the title of this film gains an extra dimension, for the man in the machine isn’t Jobs, it’s mankind.