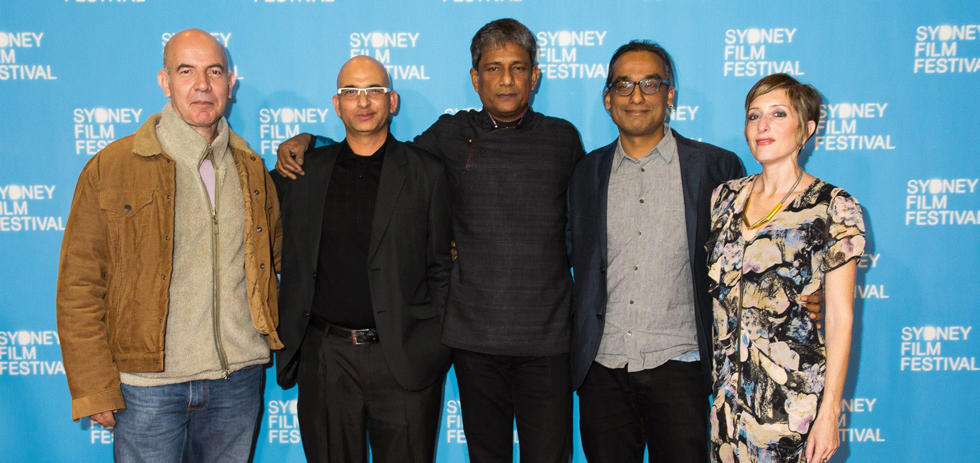

Partho Sen-Gupta’s Sunrise is a debilitating portrait of man struggling to cope with the loss of his child. Relying mostly on non-verbal cues, the film has a unique raw emotional power that would’ve otherwise been lost in dialogue. Virat Nehru caught up with the film’s director Partho Sen-Gupta and actor Adil Hussain, who plays the leading protagonist in the film for a sprawling, discursive discussion about the changing nature of cinema and the intricacy of the relationship between a film-maker, actor and the audience. You can read our review of Sunrise here.

You’ve done an examination of grief through noir which seems like a weirdly fascinating combination. What prompted this idea?

Partho: I’ve always been a fan of noir films. I’ve always watched noir films. I think that fascination started with literature. I think the basic idea of noir, at least in literature – it’s a post-war syndrome. So after WWII in the US, all these people come back after the war, all these men come back after the war. They were glorified as great people – they went to fight for the nation, they are turned into heroes. And then, post-war they come back and they have no work. All these men descend into sombre nothingness. All these stories of noir are often stories of these men. So noir is somewhere an expression of grief, an expression of darkness. It is an expression of how a protagonist feels, how one feels when one is in a depression because the world seems noir. For me, in Sunrise the idea was – I took a story that’s often dealt with – even in this [Sydney Film] Festival there are many films dealing with the same story.1

But my idea was that I wanted to talk about the grief, about the pain of being a parent that has lost a child and the incapacity to do anything to do against the way the world is, especially in India. Or anywhere else in the world for that matter. It’s about that frustration. But I also deal with an aspect that’s also in noir through Sunrise which is that somewhere, deep down the male protagonist feels castrated by the inability to do anything about the situation. And I think it’s also about masculinity, this film. How Joshi, the protagonist deals with his frustration – the fact that ‘I can’t change this situation but I’m supposed to change it because I’m the man’.

And that’s Indian social politics coming in – where men are supposed to…

Partho: Yes, of course. You’re right. The woman is, you know, she’s waiting for him to change something for her. People accuse me that I’ve structured the film in such a way that represents the polarity between the two genders. Yes, but I’m representing something that exists. It’s a problem, it’s a situation. So Joshi has to deal not only with the loss of his child but also the loss of his own masculinity. And that’s noir. Joshi falling inside his bubble, shutting himself down in a dark space. The kind of noir you’re talking about doesn’t exist in Indian cinema. There are elements of noir present but usually they’re infused or adapted into musicals – putting all the commercial elements, the razzmatazz. I think there’s a misnomer lately. You see, it’s quite chic to use the word ‘noir’. Like I didn’t use it in the beginning till someone said it was noir. I didn’t think it was like that.

Adil: I don’t think he’s ever said that [used that word] when we were shooting the film.

Partho: Yeah, we never made it as a noir film. I was told later that it was noir and I thought ‘yeah… okay… fine’. ‘Neo-noir’ – I was told that it was neo-noir and I was like ‘okay’. Then I read that a lot of Indian films in the last few years have been calling themselves ‘noir’, starting with Anurag Kashyap. But I don’t think it’s noir. I don’t think they’ve [this recent trend] understood the idea behind noir. Just because you have shadows and darkness doesn’t make it a noir film. A noir film is an idea, it’s a genre of the treatment of the film – how the characters are treated, how the subject is treated. I think that’s noir for me.

Adil, to bring you in here, as an actor – there’s so much sparseness in dialogue, there’s hardly any. There are a lot of scenes where you’re emoting, but not actually speaking. How difficult is it for an actor to do that?

Adil: In fact, I was looking forward to shoot because when I got the script – five, six years ago – I read it. I read it again. And then I actually counted the words I had to speak. And I called him [Partho] and said ‘I’ve got twelve words’. He said ‘Really? Oh, I haven’t counted. So, is that a… problem?’ And I said ‘No, I love it!’ I don’t know, I have a problem with too many words.

Though I’ve been doing Shakespeare, I’m used to words. But somehow, Shakespeare makes sense. But then, he was a great writer. Unless words are written with that kind of wisdom and depth or it’s economised and only used when it’s necessary to use. I read it [the script] again to find out whether it was a forced silence and I realised that it’s not. It’s not contrived. It’s organic. So, I was looking forward to shooting the film – let’s do it!

Your question was – how difficult it was. I don’t see it as a difficulty because words happen inside of us first. What’s written outside here (points to a newspaper on the table in front) is just a representation of me. So whether you say it or you don’t say it – as far as an actor is concerned – saying it is an extra effort. Not saying for me is better. So, I’m saved from that other responsibility of making sense.

So you feel that non-verbal communication is a lot stronger?

Adil: Yes, I just love it.

Partho: I think a lot of actors use words as a crutch to perform. They show off their dialogue delivery.

Adil: Yes, that’s true.

In commercial Indian cinema, that aspect is huge.

Adil: Oh yes.

Partho: It’s true that it can be seen as a handicap – that there are no words to hang on to in terms of performance. But for me, I think actually the film has a lot of words. They are just not said.

Adil: Precisely!

Partho: So any time Adil was performing a scene and he doesn’t say anything, for me he’s saying a lot.

Adil: Absolutely, That’s what I’m trying to say. Because you’re compensating for what’s happening inside. Words, anyway, according to Indian understanding, according to mysticism, words are the worst form of communication. It’s called vaikhari – I don’t know if you’ve heard that. Vaikhari is verbal communication and is the worst way of communicating. The highest way of communicating is when you’re not saying anything and I’m not saying anything but we understand each other. That’s the highest communication. I think it’s a great challenge as well because unless and until I truly feel something which I’m supposed to according to the given circumstances and the instructions that come from the director, it will fall flat. So, it was extremely challenging that way – in the sense that I cannot fake it. Like I cannot say ‘Had it pleased heaven. To try me with affliction’.2 You know, there are words there. (Laughs) It’s a gift. That’s all I can say.

Partho: It’s quite scary. When I showed the script around – you always show the script around to some people that ‘Hey, here’s my script’. They read it and said ‘Oh, it’s not ready’. I asked “why is it not ready?” And the reply was that it’s only forty pages long. First of all, who said that a script has to be a hundred pages long – that it’s some kind of arbitrary Hollywood decision. When you look at Screen Australia, when you apply for funding, the written script has to between 90-120 pages. It’s a stipulation.3

Adil: (surprised) Really?!

Partho: Yes, it’s a stipulation in the thing. So, often I’d increase the font size but it still won’t reach more than 53 pages! After a point, it suddenly started to look a bit ridiculous – there 18 point font big words. What I think – because the word ‘challenge’ came up – what is interesting for me as a director when I’m shooting a scene. There’s a description of the scene: that he walks in through the door and takes off his watch. That’s action. That’s the main action. But the action is just the crutch. In film school we learn the basics of how to work with actors. Our acting teacher would always say that you get an actor to sit down and tell him a simple thing – ‘I’m fed up of you and I’m going out of here’. And you tell the actor these lines and you give him a coat, a hat and an umbrella. Tell him to say the lines and as he’s saying it, ask him to wear his coat, put on his hat and take his umbrella. You’ll see that he’ll act better than if he has none of of these three things. Because, you see, since he has to do all this business, the actual saying part of it will become the least important thing. Because naturally, you don’t want the saying. What you really want is to bodily tell me that you’re going away.

Adil: Exactly.

Partho: And if he’s a good actor, he may not even say anything. He’ll just wear his jacket, put on his hat, take his umbrella and leave. And he has said without saying anything – I’m fed up of you and I’m leaving. So, that was the idea we tried to work on a lot. We were really conscious – do we really need the words here? For Joshi to say this, does he really need to say something? Can he do it with his body actions? Can he do it by wearing his wristwatch or putting something down? That is the simplest way we worked on this film. And it worked really well I think.

Talking about body language, there’s a distinct focus on the eyes. What people actually say in the film is completely opposite to what they’re communicating through their eyes. Especially, in an Indian context, these are difficult things to talk about – domestic violence and child trafficking. It seems that you’ve found a way of talking about these things without actually talking about them. That perhaps, you’re saying a lot many things, but because they’re not ‘said’ [spoken] you can do more with it?

Partho: In the Natya Shastra4 the eyes are very important. If you see any Indian dance, the eyes are very important. We use the eyes to tell what we want to say. In a lot of dance forms such as Kathakali the eyes are so important – they make them red to say things.

Adil: Permanently. It’s the entire point of the performance.

Partho: Exactly. Coming to modern Natya Shastra – which is essentially cinema. What we see in cinema is the opposite of theatre. In theatre, they [the performers] are really far away. You can’t see their eyes. In cinema, you can see eyes because we have lenses to go close to the character. And the first thing a human being sees when looking at somebody else – an animal or any living organism – are the eyes. That’s the first thing he looks at. Even if it’s for a brief moment. Because eyes give you a signal, they communicate things, ideas. It’s our primary form – before we had words. When we saw something moving, we locked each other’s eyes. So eyes communicated a lot of things very quickly – aggression, fear. You remember, as a child we were always told – don’t look into the eyes of a dog, otherwise he’ll bite you. Because he can sense the fear.

Adil: Avoid eye contact.

Partho: Exactly. Avoid eye contact. When my dad would get angry with me, I’d not look at his face! In this film I wanted to use the eyes. Eyes would tell the pain of the kids, tell the pain of Joshi. The embarrassment of the other policeman who’s trying to deal with this mother who wants him to find her child. But the policeman knows that he’s stuck in this kind of bureaucracy where he has to fill in forms. So he says, ‘I’ll let you know when we have any information’ which is an official line. But he knows inside that nothing is going to happen. You can see that embarrassment in his eyes. That’s the one thing I’ve worked with all the actors. I told them these little subliminal messages.

And cinema uses eyes a lot. If you see any kind of cinema, even Bollywood, the eyes are very important in the narration. One should not forget the eyes. When I cast, that’s what I look at first. The eyes of the characters. The little girls who are in the film are all non-actors. What I liked about them is their eyes. The very first thing. Then their body language and everything else comes in. But that comes in later. If I saw something in their eyes, then I knew it was done. The body language is something you can learn. But if your eyes are not telling the truth, then it doesn’t work. That’s what I do in a casting. I always look at people’s eyes.

Adil: I remember Ang Lee doing that to me. We were just sitting and talking.

Partho: But he wasn’t listening to you, he was just looking at your eyes?

Adil: Not even that. He [Ang Lee] made it so obvious. He asked me to get up. He took my face and held it up to the light.

Partho: I’m sure that’s a little exaggerated (chuckle). But yes, eyes are the basis of all human interaction. The lenses have made it possible because they can go very close to you.

Adil: That’s the other eye [the lens]. Very dangerous. Very non-judgmental.

Partho: No, it’s very judgmental. Because a wrong lens can make your face look…

Adil: Ah yes, that way.

Partho: Yes, extremely judgmental that way.

What works so well with eyes is that you’re not forcing your interpretation on it. A lot of the time when you say something, you’re trying to interpret the action yourself through dialogue. But the eyes tell you a lot of things that even you don’t think they are telling you.

Partho: I think in narration what is very important for me – in terms of modern cinema at least – is that everything is not said by the director. Some things are suggested. And you let the audience make it up for themselves. Does it mean that I’m going to be deliberately obtuse? No. I don’t mean that kind of cinema. Which is also very good. I like that you have to figure out what’s going on. Letting the audience participate is important. Almost like a quest. The audience needs not to just be the voyeur. It also has to participate in the quest. So the structure of Sunrise – a lot of people say it’s broken up, non-linear, what is real or not real we don’t know. But I let the audience work it out. Some people work it out in one way. Others work it out in a completely different way. And that’s fine.

Talking about audiences. I feel contemporary Indian audiences have been very spoilt. They have been very passive in receiving messages – let the film do all the work and they’re just there to “enjoy” the film.

Adil: Sit there. Naach meri jaan [Hindi colloquial phrase which roughly translates to “Dance for me”].

Do you think this trend is changing with new Indian film-makers? Right now, it’s an interesting time for Indian cinema where Indian audiences have started to say that ‘Oh, maybe we should do some work’. That you’re not just going to the cinema to be passively entertained.

Partho: I don’t know what you think. My view is very pessimistic. (Laughs)

Then it will be interesting to compare both your views.

Adil: I’m a bit more optimistic. Not very optimistic. Uh… (laughs) I think it’s a drop in the ocean. A lot needs to change. Especially because India has such a strong history of participatory audiences and viewership. For example, the theatre tradition. I’ll just tell you briefly. The theatre tradition, right from ritual performances in ancient times, the audience was a very willing participant in the process with people who were mediating between the known and the unknown. So, you as an audience member, come with faith and you sit there. And the other person, who is an expert in the meeting of the known and unknown world. If you look at the contemporary position from that point of view, it’s in very bad shape. We’ve become a nation of feudal lords. They say ‘Dance. I’ve paid you and you have to entertain me’. That’s what it’s become. We are far away from that kind of active participation, apart from perhaps, painting and art exhibitions. There at least we try to find out what the hell is happening!

Partho: Yeh kya hai? [What even is this?] At least there’s some form of questioning.

Adil: That’s the beginning. The first step. In cinema, I think we are far away from that. Very far away. But few films recently – like have you seen Court?

I’m going to be seeing it here at the Festival.5

Adil: That film, in India, thankfully it got released. Because it got an award in Venice.

Partho: So people went to see it.

Adil: (chuckles) Yes, that’s why people went to see it. At least to find out ‘what is this’.

Partho: Ki yeh hai kya? [What is it after all?]

Even if it was a misguided reason to see it, at least audiences went. That it’s got an award so let’s go and find out what this thing is…

Adil: People have gone and seen it. And at least in urban centres and cities, people are watching it and they’ve liked it. Some people are even talking about it. But as I said, it’s a drop in the ocean. But at least it’s a drop. And I’m hopeful – I’m now 51 years old – and I hope it changes faster than I age!

Partho: I think it’s not just a problem in India. It’s a problem everywhere because of the way cinema is delivered. It’s the delivery that’s changing the perception that it’s purely entertainment. When I mean delivery, I mean commercial delivery – such as Netflix, or that you can see it on your phone, or that you can see it when you’re taking a dump. You know what I mean? You can see it on a plane, on a small screen. It’s all a problem of cinema delivery. How does the whole process start? Well initially, you bought a ticket. You made a conscious decision as a spectator that I’m going to watch this film. Buying a ticket was this conscious decision. If a film is 90 minutes long, I’m going to make that time for the film. 90 minutes hum arpan kar rahe hain [That you’re devoting those 90 minutes to the film. ‘Arpan’ implies an act of devotion. So as the audience, you’re offering yourself to the film].

You go into a hall. Everybody sits around this thing – this central object – which is the screen. The lights go off. Once upon time we didn’t have mobile phones in our pockets so we were just sitting there. And when the screen lit up, you were completely in that space. It’s really a question of ‘arpan’. You devote yourself to the film. You came out and you took away whatever you could. Today, it’s not the same. Today, the thing is that you can pause it, record it, see it tomorrow. I’ve seen half, I’ll see the rest tomorrow. Did you see that film. Yes, I saw 3/4th…

Adil: 1/4th is left.

Partho: But what’s the 1/4th that’s left?

Adil: Oh, I had a meeting in between.

Partho: Or I had a phone call to attend to. So, that’s the major problem. The we see movies now.

Do you think that other commercial elements such as marketing etc also come into play?

Partho: Yeah, it’s all linked. The delivery system is decided by commercial elements.

Everyone has kind of pre-decided because they even see a movie about what kind of film they’re expecting. Whether you’re going to like the film or not like the film because there are teasers and trailers…

Partho: Exactly. Exactly. There’s no discovery. I remember when I grew up in Mumbai. Every Friday in the evenings, we all used to go and see some crappy movie. Any film that used to release on Friday night. Basically so we could go out and drink and smoke and what not. It was a trip. It was an experience. You were baffled: what are they going to show us this time? After some of the films, you came out feeling ‘Fuck, this amazing!’

I remember films, you know, they may be crappy films, but I came out of the hall at that time – when I was about 16 or 14 years old – I felt happy. That’s because you had no idea what it was going to be about. Even if you’d seen the trailer, there wasn’t much given away. You had no idea about it. I think that’s gone. The mystery is gone. So it’s tough for film-makers. You have to keep on surprising people and keep on finding a new way of telling a story.

Adil: That’s why I think festivals are good.

Partho: To an extent. The problem now is that festivals also get pushed.

Festivals seem to have an obligation of showing certain kind of films.

Partho: Because they want some distributor to pick up three films. And the distributor says I’ll give you three, but you have to show the fourth one. The fourth one programmers don’t like but they have to show it, otherwise they’re not getting the other films. So, the power of the distributor has become stronger than the power of the programmer.

Adil: And film-maker.

Partho: And film-maker. Of course. Film-makers are very low in the pecking order. They are not even mentioned. The Indian press completely ignored the two Indian films that were selected for Cannes and covered all the ladies who went there in this costume and that costume.

Adil: Which are the two films? Even I don’t remember…

Partho: (Laughs) There was Masaan and The Fourth Way.

Adil: The delivery system is a consequence of commerce dominating the arts.

Partho: I read this article recently about how Netflix chooses its films. 70% is decided by bots and 30% by humans. So the choice of whether Netflix picks a film or not is decided by feeding data into a machine. The machine then spews out a decision whether the film should be acquired or not. Once upon a time guys would go see a film a film and they’d acquire it because they felt something. You know, let’s pick this film up and we’ll see. Sometimes that worked, sometimes it didn’t. That’s gone. It’s the bot who decides now.

You mentioned that film-makers such as yourselves are very low in the commercial pecking order. How does that affect you as a film-maker and actor respectively?

Partho: With Sunrise, because it wasn’t a traditional film – lack of dialogue among other things, there were a few problems. Mainly people thought that the script wasn’t ready. In all indie, author driven films, the director starts the project. He has the concept, the story, he gets the funding. But it’s all step by step. So I guess as a director you are in a position of power when you start off. But I guess it’s like asking if the potter is important or the clay? It’s a very difficult thing to say. I can’t do a film if he [motions to Adil] is not with me. So, I don’t think there’s a hierarchy in those terms. But yes, he’s [Adil] is on screen. He’s my alter-ego on screen. He’s speaking my mind on screen. He’s representing my vision on screen. So I cannot elevate or deflate him. He’s the one in power. He’s actually an extension of me in a certain way. Whether they are male or female characters, they are all extensions of me. I’ve seen them in my head.

Turning to the actor’s perspective. Adil, you’re from the National School of Drama. And a lot of NSD graduates get typecast in arthouse cinema or in commercial cinema they get slotted into certain kind of roles…

Adil: Villain!

Exactly. So what do you have to say about the changing role of actors in Indian cinema? Are you comfortable with the current situation?

Adil: I guess it would be different with different actors. It all depends on what kind of actor you want to be and what is your vision as an actor. I’m very happy with the kind of roles that I’m getting from arthouse cinema – that I get to act in some sensible scripts at least. Some of them are great. Most of them are terrible (laughs) no, really! Out of twenty, maybe two which make sense. I don’t know how to say this because it’s only my perspective. I wish it was the perspective of other actors!

Because I teach acting as well. And I try to propagate that any actor who is in love with the craft of acting. Or just in love with acting, forget the ‘craft’ part. Craft depends on how far you’ve delved into it. The entire process of acting is like Partho says, I’m his extension. That means a little bit of him is within me. And if wasn’t within me already, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. Through each project, each piece of work that I do with different directors, I discover a little bit of me that I had not known before. And that most probably is the reason now – it keeps changing – why I act. To find out that I’m also a little bit of this and a little bit of that. I’m also Hitler and Christ and all the other characters in between in so many ways. This should drive everybody to act. This is a lifetime opportunity that you’ve been gifted, or rather, you gifted yourself by choosing to be an actor. What comes after you act – the applause, walking the red carpet is again a controversial thing…

You see, you may not get it. You might not be famous. You might not get money. Would you still act? And I would still act. Because I’m in love with the process of acting and what comes after it is a bonus. You may or may not. If you get it, wonderful. I’m sitting here with you, somebody’s served me this lovely cappuccino. Seeing an Australian city where I’ve never been before. These are all cherries on the cake.

Thank you so much both of you for your time. This has been a fascinating discursive conversation. My best wishes for Sunrise. I’m sure it’ll do very well.