In his introductions to both the International and After Dark Animation Showcases, guest programmer Malcolm Turner made special note of how animated films, by the numbers, are more the domain of adult audiences than children. It’d be safe to take his word for it as the curator of a dedicated Melbourne festival for years, but that binary has been an appreciable factor since Pixar shattered the medium’s earth twenty years ago via Toy Story and made children’s films with stealthy adult humour and themes the norm. With that studio’s newest release Inside Out curiously bereft of the Sydney Film Festival gala screening that Monsters University enjoyed in 2013, Turner has been called in to whittle over 3000 submitted shorts down to a series of showcases that each gleefully blurred the line over around 60 combined minutes and left me feeling hungry for more. Both showcases exhibited not just the physical humour and gags that Dendy Shorts attendees are accustomed to from their animated offerings, but a rich cinematic literacy with as much maturity as any other of the festival’s short offerings.

In that spirit, let’s begin with Jackin’ Off In Traffic.

I understand that my colleagues at 4:3 were baffled over the inclusion of one or two films in this year’s Official Competition, and even the Festival itself. I haven’t seen any of the ones they’re talking about, but if this horndog folk jingle by YouTuber Kai Alden is above board to play on a festival screen as part of the After Dark evening, than the floodgates of taste have yawned open with eerily Tweened precision. It has all the hallmarks of the same Newgrounds pap among which the likes of Happy Tree Friends grew so popular in the last decade, full of lamentably crude sexuality and racial stereotyping. It also has the gall to pre-emptively guard itself as a South Park-esque vanguard of political incorrectness; just check that invective URL in the first frame (the domain, tellingly, is expired). Between it and the similarly witless Bird and Cactus Crack and Barbecube, it exists to make the pre-teen boys in your family piss themselves laughing, and I suspect there’s many a digital native who’ll nostalgically remember being that exact same child once, flitting between eBaums World, Liquid Generation and other sites for block-headed satire like it.

That said, there was tremendous value in having this kind of vulgarity in Turner’s showcase, which goes beyond feeding some rancid wolf in ourselves. There’s considerable historical value, since anyone looking to document the form’s changes in the last decade will have a huge task ahead of them by having to account for that boom of Flash-animated cartoons online, and for better or worse, well-viewed and juvenile fare like Traffic has to be acknowledged as part of the, ahem, landscape. It also acts as a yardstick by which similarly visceral but superior shorts reveal themselves. The British oddness of Joel Veitch’s I Love You So Hard ferries a bleak view of male sexuality, and Christian Lavarre’s Lesley the Pony Has an A+ Day! might need a trigger warning for its hard-edged disruption of loony, beautifully drawn Adventure Time jollies. Other shorts in the series flowered in the contrast; in no other context would Seeds!, Christopher Siemasko’s absurdist one-joke that flies by in thirty seconds, be such a tonic, nor would Joe Sams’ Cute Midwestern Family Moments and Annette Jung’s The Penguin feel so respectively Korine and Aardman-inspired in their own comic reveals.

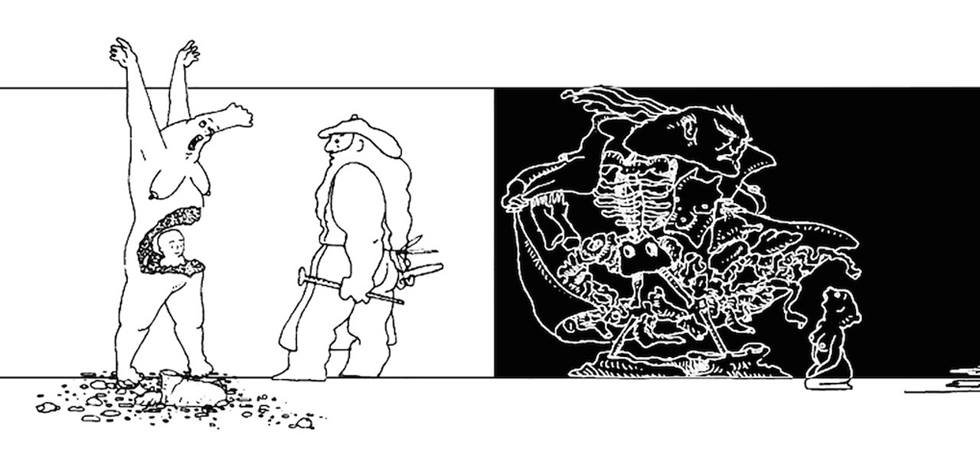

On the lighter end of the After Dark spectrum came more noticeable technical prowess. Steve Girard and Josh Chertoff’s rap video-cum-drug trip Wawd Ahp and Dutch artist Rosto’s Splintertime shine not just in their intricate grotesquerie but in the fusion of 2D, computer, stop-motion and live-action forms to get there. Aaron Guadamuz‘s Staring Window, Woo Jin’s Beautiful and Priit Tender’s House of Unconsciousness also do madly surreal work in the realms of traditional animation and carnal surrealist forms, but also capitulate in their titles and premises to the need for a conceit with which we rationalise what we are seeing. This would be fine if not for the overshadowing majesties of Jeanne Boukraa’s With Joy and Merriness and Mario Addis’ Nude and Crude, which mock such framing devices by using animation to erode discourses of boy and society within a few breathless minutes. The latter was my favourite of the night for its calm abjection, scandalising without a trace of the anger and provocation of the other shorts due to minimalistic visuals and score.

After Dark proved to be a night for bawdy thrills, but the International category rose above its incredibly loose name (shouldn’t all the showcases be culturally varied anyway?) to deliver some of the finest short film-making of the festival, period. My mind immediately goes to the stark colours and angles of Bobby de Groot’s Cruise Patrol, which thoroughly earns the right to thank Sergio Leone and John Carpenter in the credits by bundling those techniques into a wild emotional sequence. Other efforts with a grand scope included Jossie Malis’ Bendito Machine V, a Kickstarted cradle-to-grave account of the human race as observed by a robot and drawn in silhouettes reminiscent of wordless indie video games like Limbo and Kentucky Route Zero, and Patrick De Carvalho’s Juste de l’eau (gracelessly translated as Nothing Else But Water), a bounding symphony of yearning anthropomorphic pigs and impossible Lisbon architecture.

But what could surpass the singular mortification of The Pride of Strathmoor? Many reminiscing film enthusiasts will search their memory for an animated image that penetrated their nightmares and come up with a mere Disney villain, but Einar Baldvin, an Iceland-born alumnus of the CalArts program that has birthed the Mouse House’s best talent, finds a bleaker pit of madness and despair in John Reitman (Geoffrey Gould), a 1920s Southern pastor driven mad by racial hate and fear. In huge and blotting black brush strokes, Baldvin commits to pages and pages of grimy, crumpled cels the entrails of Reitman’s worsening paranoia at proud black men, anchored by the increasing panic heard in Gould’s whispering of excerpts from his memoir. The quivering of frame-by-frame animation, usually an innocent signifier of laborious effort and craft, come to symbolise the preacher being wracked by his own insanity. The spate of images Baldvin makes tremble in this instability is utterly awe-inspiring: visions of black suns, smiling faces, street boxers with muscles drawn in repulsive curls of flesh, all each passing through time in the discordant ebbs and flows of an unstable mind (unsurprisingly, he’s adapting an H.P. Lovecraft story next). It swept through the festival audience like a cold wind, and any chance to be hushed by its strobe-lit terror should not be missed.

Thankfully, it was a bold shadow on an otherwise eclectic set of shorts that won their own comic victories. The McLeod Brothers‘ two-minute romp Scoop plays like a UK answer to the cresting wave of knowingly surreal network cartoons like Regular Show and Rick and Morty. Manabu Himeda‘s Play Like a Driver is a fever dream ripped from the wee hours of Japanese TV programming, so relentlessly upbeat and wild as to leave the festival audience in scoffing confusion, which should be a very good thing to very specific people. Dax Norman’s experimental reel Genuine Suede overlaps with After Dark’s fondness of Dali-spirited scribblings, and makes the French short after it, Chaud Lapin, a charming antidote in its stiff and hyper-detailed sketch about animals with very human physicalities and libidos. Also utilising animals is my favourite comedic short Gunther, Pixar animator Erick Oh’s seven-minute brain slap about a menagerie of animals pounding each other in their dance around the food chain that dictates their tiny lives. A lovely, low-key contrast to all of these is Me and My Moulton, a gentle childhood reminiscing by Norway-born Oscar winner Torill Kove, which still delighted the festival crowd even as an audio delay plagued the screening (thankfully, it’s up on YouTube in one piece).

All of these shorts touched on a greater storytelling tradition than public perceptions of animation account for, and just as online spaces have made them that much easier to deep-dive into, so too can a lot of the work and talent found here. With Vimeo tightening any remaining distribution hurdles, a raft of short film-making that pokes hard at notions of good taste or recalibrates them is waiting for those exciting unfamiliar with it, and for those who are familiar thanks to Turner’s smart packaging, there’s every opportunity to chase them down or share them all over again. I look forward to doing as much and then – judging from the solid turnouts at both – getting to do it all over again next year.