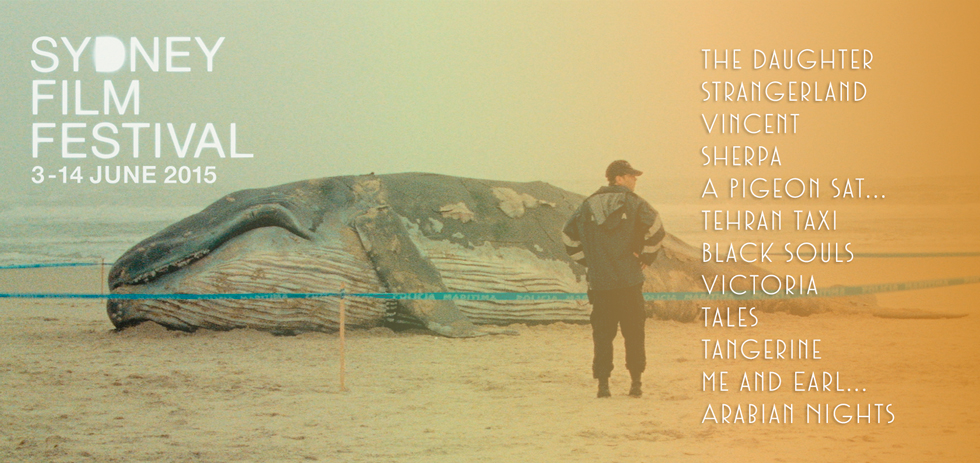

In our Sydney Film Festival Official Competition Roundtable for 2015, we have gathered together members of the editorial staff who have seen all, or nearly all, of the competition films to briefly discuss each of the contenders. The actual winner of the Sydney Film Prize this year, as announced on Sunday night, was Miguel Gomes’ Arabian Nights.

Participating in this roundtable are Conor Bateman, Jeremy Elphick and Imogen Gardam.

The Daughter (dir. Simon Stone) – AUSTRALIA – Review

Imogen Gardam: This year’s festival saw not just a large number of Australian films, but a surprising number of stage-to-screen adaptations, with both Opening and Closing Night films (Brendan Cowell’s Ruben Guthrie and Neil Armfield’s Holding the Man respectively) coming from theatrical roots. Jeremy Sims’ Last Cab To Darwin also began its life on stage thirteen years ago.

The standout theatrical adaptation, however, was by far and away Simon Stone’s The Daughter, adapted from his play The Wild Duck, which was itself a radical adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s play of the same name. Stone has made the leap into film with aplomb and confidence, delivering a cinematic work that feels deeply situated in its form and setting, drawing on the beautiful palette of its natural setting and the incredible performances its cast deliver to craft a melodrama of heartbreaking impact. Odessa Young, as the eponymous daughter, is extraordinary as the hope for the future, the promise of the next generation upon whom the sins of the last are visited. Ewen Leslie is an absolute revelation as Oliver, investing us so completely in his relationships that their unravelling is truly devastating. The film is constructed like a memory, as though the characters are looking back on it, with the dialogue track at times running separately to the visuals and the dreamy and verdant natural beauty of the setting feeling otherworldly. There is something to be said for the ephemeral nature of theatre, and its translation here as a passing moment of human tragedy is deeply affecting.

Conor Bateman: The theatre to film trend is clearly there now in Australian cinema, and on its face that seems almost a step backward – whilst we’re getting the talent of the stage trying their hand at filmmaking, it’s also more of a safe bet, having a rock solid script to start with. That noted, and with fears it would be little more than a handsomely told story, I was fairly stunned by how strong The Daughter was, not only as Simon Stone’s debut, but also as an Australian melodrama that managed to avoid a sense of falsehood; whilst the plot, very much imbued with the sense of Greek tragedies Stone has directed in theatre, lacked any real narrative tension, the characters are so compelling and their construction is so nuanced and the performances, in particular Ewen Leslie, are so deeply steeped in this compelling realism. Coupled with Fell from last year’s competition, see an interesting merger of seemingly simple morality tales with beautiful rural cinematography. I don’t think it entirely lands the emotional climax, but it’s still a very impressive Australian feature, and I hope it does well at the box office, though it might be a big ask.

Jeremy Elphick: I thought this was a phenomenal film and one of my broad favourites of the competition. It didn’t really play into any clichés that Australian cinema is usually prone to and – while the Greek tragedy structure is going to have obvious narrative arcs in some areas – had one of the strongest opening 30 minutes or so at the festival. Ewen Leslie’s performance was phenomenal, however, the majority of the wider cast matched this – in particular, Odessa Young who plays Hedvig. I think that Young’s performance is that of an incredibly promising performer, with a sense of the subtleties that are genuinely important in a tale so steeped in familial interpersonal relationships. This is one of the few films I’ve seen in recent years where an initially idealised family came off as so believably ideal. Stone opts for intimacy over exceptionalism and allows the collapse – and the passion that fuels it – to hurt and affect the audience so much more viscerally.

I feel that one of the biggest flaws in the film come in the misuse of some of the bigger names, especially in the way Miranda Otto’s character is written. Her actions are never contextualised as reasonable in any context and she’s kind of sidelined throughout as her character is often positioned as a simplified cause of a lot of problems that are initially constructed as complex. This is, however, a fairly small criticism in the face of the achievements in originality, composition and emotion that are present in The Daughter; one of the strongest Australian films in recent years.

Strangerland (dir. Kim Farrant) – AUSTRALIA – Review

Conor: Even in terms of scheduling, it’s interesting to compare The Daughter and Kim Farrant’s Strangerland – two Australian films led by big name actors that deal with the destruction of the idea of family. I think what Simon Stone’s film achieves in nuance, Strangerland tends to be a little too blunt in exploring its themes; the first indication of this approach is having the diary of Lily being read out in voiceover, but rather than diary entry it’s this warped poetry that really tries to instil in you this sense of frustrated identity, but instead just feels totally unreal. It’s got some really interesting production design and a few striking sequences – the dust storm scene in particular – but it feels like Strangerland is bogged down by a lot of narrative problems. The invoking of Aboriginal culture goes from restrained to really suddenly forced, the outbursts of grief as sexuality is too unsubtle and, the primary issue, the characters of Catherine and Matthew, the parents played by Nicole Kidman and Joseph Fiennes, are just so uninteresting to watch, despite the fact Kidman turns in a mostly strong performance. We’re stranded with them in their confusion, but they aren’t interesting enough characters to make this confusion compelling. This is further highlighted by just how great Hugo Weaving is in a supporting role, and his subplot, propelled by his wonderfully nuanced performance, is a vastly more interesting aside.

Imogen: The fallout of missing children, lost to the natural forces of the land, has a history in Australian cultural production, from Peter Weir’s 1975 Picnic at Hanging Rock, which heralded a new era of Australian cinema, to Rachel Perkins’ 2001 musical non-feature, One Night the Moon, which was based on the true story of a girl going missing in the Australian outback in 1932. Whereas Perkins’ short grappled with the racial tensions that flare up in small communities around these incidents, depicting the sharp cultural divide in our relationship to and understanding of the land, Farrant only suggests this divide as people begin to point fingers, working them into the narrative as interesting beats and points of tension that are never properly explored or satisfyingly addressed. Likewise her depiction of the moral panic surrounding female sexuality: Farrant brings to the forefront some really engaging and promising ideas around the way Lily is perceived, while shooting her like a perfume commercial, following them up in Catherine’s expression of her grief, which creates a fascinating foil for her daughter, but never really takes these ideas any further, instead leaving us with some striking visuals and a narrative leading nowhere.

Jeremy: I feel like Strangerland has a lot ambition and intent as a film that, at some stage in the filming or production of the work, fell apart completely. It could be in the stark contrast against a year of particularly strong Australian films (the Daughter, The Last Cab to Darwin, Sherpa, Holding the Man, and Women He’s Undressed), or it could be the general weakness of Strangerland as a film. With a weak narrative, a lack of any coherent or lasting commentary, and a group of characters that don’t really draw the audience in, I think it’s a bit of both.

Vincent (dir. Thomas Salvador) – FRANCE – Review

Jeremy: It’s genuinely difficult to justify a film like Vincent existing in the Official Competition. It’s the sole film out of France in the competition, and it barely meets the competition criteria in the first place. French cinema is one of my big weak points in film knowledge, but it’s difficult to imagine that – going under the assumption that France seems to always have a spot reserved in the Official Competition – nothing was more deserving than Vincent. But perhaps this signals the growing hunger for a broader film landscape that moves away from the central parts of Western Europe. I think the strength of the films from Iran, Portugal, and oddly, Australia show this quite a bit.

Imogen: The French film industry is blessed with a great deal of government funding, drawing on a tax on all international films distributed in France, and as such is capable of a prodigious amount of production, which perhaps makes Jeremy’s point about this being the best France has to offer even more pointed. Vincent seemed to offer an interesting premise – a superhero film done in a naturalist style – but ultimately failed to deliver beyond this. At only 77 minutes it felt incredibly long, and while the idea of superheroes without spectacle (in today’s oversaturation of superhero titles and franchises) makes for a good logline, it made for relatively unedifying viewing.

Conor: The European influence, as always, is strong on the comp, but I’m in total agreement with the two of you – France surely has more to offer than this. My review walked through most of my problems with the film, which consist primarily of how uninteresting Vincent actually is, how lazily written the film is and the sense that its place in the competition would have been the only thing that would ensure it sells tickets.

Sherpa (dir. Jennifer Peedom) – AUSTRALIA – Review

Jeremy: For me, Sherpa was one of the films that I didn’t have any expectation or knowledge about going into. With that, it was also one of the most surprising in terms of its strength. The documentary is a product of an unforeseen tragedy, where – initially planning to document residual tensions from a confrontation between climbers and sherpas the previous year – Jennifer Peedom’s film screw ended up at Everest at the time of the 2014 disaster wherein 16 sherpas died. In this, Peedom hasn’t made a documentary about the events themselves, but instead, the tensions between humans that ensued. It captures a rare moment where the prospective climbers are at their most desperate (as the sherpas decide they wish to close down the season out of respect) casting a light on the pervasive selfishness, lack of genuine concern, and disregard for the culture and land that they function as tourists within.

My biggest issues with Sherpa come down to the nature of the competition – in that, the film didn’t feel like it was genuinely cutting-edge in the way it was constructed as a documentary. It was full of information that needs to be spread, especially in the wake of the most recent disaster in Nepal; about the impacts of tourism on culture, the disregard for human life that ambition can create so easily, and the wreckage that money can create on the natural world. That said, it was a film full of marvellous landscapes, shot in the most conventionally beautiful ways. This is a problem in selecting a documentary for the competition. The shots never felt like they were anything that you wouldn’t see outside of a documentary on National Geographic and in an Official Competition in a film festival that marks its criteria as “cutting-edge” amongst other things, this is something genuinely brings the film down. It’s an incredible source of information and a solid character study, but in terms of cinematic flair it feels a bit lazy.

Conor: I’m not as enthusiastic as you about Sherpa but it is definitely visually impressive. Its premise is likewise strong, and the stroke of luck that is filming on the day of this horrible accident makes the film an interesting document of tragedy and crisis, in addition to the damning portrait of Everest-climbing tourists. It’s just that it becomes something conventional, when it seems to indicate it will be something innovative or different. The cinematography moved from the POV shots and actually tense visuals to this more reserved, swooping shots of mountains, rendering it something akin to an Attenborough documentary with a clearer social conscience. It’s structure, as well, showed no real signs of innovation; as such whilst it’s an impressive Australian documentary, and an interesting look at a culture in Nepal, seems to lack the spark that other documentaries that have played the competition in years gone by (The Act of Killing, Stories We Tell) have had.

Imogen: Sherpa was visually stunning – I was struck by the images that Peedom was about to capture and create in what were incredibly difficult production conditions, particularly given the nature of the film itself changed midway through shooting, when tragedy struck. She shoots the villages and the minutiae of the sherpa community with a captivating reverence. It was beautiful, but I agree with Jeremy: it was not necessarily cutting-edge. The film is perhaps particularly timely – the first trailers have just been released for Everest, Baltasar Kormákur’s 3D mountain adventure film based on the 1996 Mount Everest disaster. Following on from Sherpa’s exploration of the white-washing of depictions of Everest, and the slow revolt of the sherpa’s against the disregard for the risk they undertake, it feels especially frustrating to see an entirely white cast take to the slopes.

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence (dir. Roy Andersson) – SWEDEN – Review

Conor: More than anything, I felt a certain disappointment with Andersson’s latest, both in the arc of his career but also in terms of the structure of A Pigeon, which seems to peak five minutes in and then lumber along through visually interesting but often overly broad sketches. I’m a fan of You, The Living, his shorts, and have already written of my fawning adoration for his commercial work, so much of the way I view Andersson’s films has to do with duration and pacing. In A Pigeon I think it felt off, it dragged a lot in its second half and the intricate interweaving of characters early on seemed to drop off in favour of more random sketches that, I think, lacked the punch of his earlier work. It’s still not particularly bad, the artistry on show is so clear, but as a new Roy Andersson film, this one fell mostly flat for me.

Imogen: This was the first Andersson film I have seen, and has left me wanting to discover more of his oeuvre. I’ve been intrigued by the film ever since I came across the title in the program for Venice last year. It stands out. I was completely taken with Andersson’s visual style, and found that I felt just a little bit unsettled by the pastiness of every character, the locked off shots, the slow movements. It’s unlike anything else I’ve seen recently. I loved the sense of the depth of frame and while I didn’t love or feel invested in every character or plotline, I was sold when Andersson put an entire army through the back of a scene without missing a beat (or losing that sense of absurd despondency).

Jeremy: I agree with Conor a lot here. I really loved You, The Living and I think it’s the stark contrast between the two and the expectations I had of A Pigeon as a result that really let me down. The scope felt narrower in Andersson’s most recent work, the characters felt much thinner, and it felt far less coherent overall. Roy Andersson is clearly a deeply imaginative character – as both his previous works as well as A Pigeon show. This imagination is on display in full force here, but there isn’t as much cognition – let alone cogency to bring it all together like he’s done in the past. It just feels like something is missing.

Tehran Taxi (dir. Jafar Panahi) – IRAN – Review

Conor: Having been only impressed by This Is Not a Film and not having seen any of Jafar Panahi’s pre-ban films, his latest, the Golden Bear-winning Taxi (unfortunately re-titled in Australia to Tehran Taxi, I guess out of fear someone might confuse an Iranian festival hit with a Jimmy Fallon/Queen Latifah vehicle) was appealing to my interests conceptually, this idea of vignettes floating around one another through a fixed location and character is an interesting act of pared back scope to allow surprising creativity, an inverse Slacker, if you will. Having seen the film, though, I’m completely blown away by it, and I think it’s a sight better than everything else in the competition this year, for me nothing comes close. The opening long take, that winds its way through the streets of Tehran on Panahi’s dashboard, only to be turned around to face the passengers within, is one of the best shots of the entire festival and a microcosm of the whole film – so visually simple yet pulsing with ideas, movement versus stasis, the blurring of fiction film and documentary, the awareness (as also in Victoria) of the actual physical process of having actors wait in a certain part of the city as the beginning to a scene – art imitating life imitating art. It’s incredible.

Imogen: There’s an honesty to Taxi that is demanded by its circumstances. Somewhere between the blurring of the line between fiction and documentary, Panahi captures a city in motion, its inhabitants offering small glimpses of themselves and their lives within it. It is striking in its simplicity, both conceptually and in terms of its execution. Watching Tehran pass by outside of the cab, embodied in the different people who pass through it, is thoroughly engaging. The film is full of moments of humour and levity, while also delivering meditations and dissertations on the human condition, whether from a mugger who suggests criminals should be beheaded (am I remembering that correctly? Was he calling for beheadings?), or an old friend of Panahi’s who refuses to report the man that attacked and robbed him because he knows the fate that awaits him, and the circumstances that forced him to do so. To sit in a packed cinema with two thousand people and watch cultural practices become subversive and secretive, from the black market trade in DVDs to the rules Panahi’s niece must obey to make a “screenable film”, feels like an enormous privilege.

Jeremy: Taxi is a fascinating work that seems to build most notably on the structure and set-up seen 13 years earlier in Abbas Kiarostami’s Ten – a film also set entirely within a car driven by a single individual for its duration. While Ten intended to focus on dilemmas in Iranian society (particularly in reference to the female driver), Taxi re-contextualises this concept into a few hours in the life Jafar Panahi; both the director and fictionalised star of the film. Taxi is about film in Iran on both the distribution and production levels, it’s about a man living in quaint defiance of a ban on him making films, and it’s a study of Panahi’s own position in Iran – as both a quasi-celebrity figure as well as a reserved and remarkably self-assured character.

Black Souls (dir. Francesco Munzi) – ITALY – Review

Conor: A deserving winner of the cinematography prize at Venice, Black Souls is a gorgeously shot mafia tale that wavers between poignant minimalism and overly reductive plot points. It’s not as if we’ve never seen something like this before, even with the greater focus on family outside of the mob here. Its slow pace, as Brad wrote in his review of the film, actually is a virtue, there’s breathing room and the lack of exposition is very compelling for a film in this genre. I question its place in the competition this year, despite the fact that it just swept the Italian Film Awards, because it really doesn’t do much except be mostly good. It’ll do well at the box office here, though. Palace have it, and it’s one they’ll be able to effectively market quite easily.

Imogen: I was less enamoured of Black Souls than Brad, and found it far less compelling than Conor. While I appreciated the slow pace and found the sparse exposition effective, I never felt that I cared enough about the characters to stick with it. By the time the third act climax came around, I found that I had clocked out, and while the cinematography was striking, it wasn’t enough to hold me where the narrative could not.

Jeremy: I think I sit somewhere in between Imogen and Conor. Black Souls is a breathtaking and beautifully shot film, but in terms of plot and momentum there’s not much to offer – especially if you go in expecting a sort of fast-paced mafia flick. It’s not that, and once I settled into that realisation I had a lot of fun with this as a sort of inverted gangster film, where I found myself drifting towards focusing on the construction of shots and the general detachment from any sense of motion. I guess this lead to me having a similar issue as Imogen though, in that, I didn’t really have much concern about the actual characters because I’d been paying so little attention to them.

Victoria (dir. Sebastian Schipper) – GERMANY – Review

Imogen: The one-shot film holds a particular fascination for audiences – we’re immediately engaged in the film’s construction, and the process by which it is shot can feel present in our understanding of each scene. In a medium that fluctuates between hiding its processes and actively triumphing them (as we demand the computer generated work look as “realistic” as possible, despite knowing it is contrived), the one-shot occupies a strange place in the contract made between filmmaker and audience. It can also, unfortunately, be a gimmick. As such, filmmakers often need to work to create narratives that engage with the production process, and can transcend it – we shouldn’t spend the entire film waiting to catch out to camera operator, or trying to spot where they might have cut. In Victoria, Sebastian Schipper has more than delivered, creating a film that draws on the honesty and lack of illusion inherent in the nature of the one-shot. Victoria follows the titular heroine on a night out in Berlin, where she tees up with some local boys as they roam the city. The improvised dialogue and intimacy of the format makes their burgeoning relationship entertaining and engaging as it builds completely naturally to a second act escalation that carries its audience with it. The film becomes high-adrenalin and high-stakes but never loses its honesty. It left me exhausted, wired, and very stressed, in the best possible way.

Conor: Victoria definitely has some narrative issues in its final half-hour (the social morality injected into most bank heist films tends to bore) but it is, as I wrote in my review, an inventive, compelling and thrilling watch. The sudden lurch from a remarkably well set up romance to this simplistic thriller plot is likewise an amusing experiment, as the flimsiness of some of that plotline is irrelevant considering the film banks on the audience investing in its characters, something I think it definitely achieves. Schipper’s debut is a pretty remarkable watch, and cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen somehow makes every single sequence visually arresting. The Nils Frahm score (with a DJ Koze assist), in addition to the strong performances from everyone it in, makes Victoria not only a fun experience but also a well crafted film on the whole.

Jeremy: Victoria was an interesting one for me. The first hour had this incredible pace to it, Nils Frahm’s score is phenomenal, and the scenes filmed inside the club at the start were engulfing in the best way possible. The problem with Victoria for me, was that it gave me a taste of a film I really, really wanted to see; something brief, temporal and fleetingly special – then it yanked it away, turning a flick that had such a poetic start into every moralistic bank heist film. I guess my issues are similar to Conor’s but I found them far more jarring. Victoria played with tension in a really fascinating way at the start, but by the end it was engaging in every robbery cliche I could think of. I wanted to love this movie, but the way it fell apart really stuck with me more than anything else.

Tales (dir. Rakhshan Bani-Etemad) – IRAN – Review

Conor: Another Iranian film which I lacked the prerequisite knowledge for was Tales, which on its face is a pleasant enough collection of vignettes about connection and humanity, some vastly more interesting than others; in fact the final story, a duologue in a cab, is one of the best written and performed sequences in the whole festival, a masterclass in simplicity. Having read your review, Jeremy, I see that there’s a whole lot more going on with regards to extension of narrative and character.

Jeremy: This was a weird competition choice. I really liked Tales , but I definitely came at it from a vantage point of being familiar with Bani-Etemad’s earlier work; particularly, the City trilogy . It contextualised the characters a lot more for me, and I was familiar with her approach a lot more than I think the general SFF-crowd were, in a country where few Bani-Etemad films have reached its shores. At the heart of the film are a series of vignettes that are short enough to be deemed ‘screenable’ in Iran, and in this, this is a movie that shows an alternate method to working within the country’s strict cinematic landscape. Another contrast comes in Bani-Etemad’s content: she focuses on the downtrodden, drug use, and narratives that most viewers in Sydney wouldn’t expect to be common in Iran. As a film that gives a broader portrayal of Tehran than Panahi’s film, there’s a lot to take from this one.

Tangerine (dir. Sean Baker) – USA – Review to Come

Jeremy: Tangerine is my pick from the competition as a work embodies “cutting-edge”, “audacious”, and “courageous” filmmaking. Making a film about transgender issues is a task that filmmakers have had serious issues with in the last few years. One of the biggest missteps in the past has been in a lack of consultation with the trans community. Tangerine is a film that is something that emerges out of being a collaborative project. At times, it feels like an L.A. Christmas movie, at other times there’s a few dialogue scenes that flow like Spike Lee at his best. It’s a film that mixes an improvisational first-time cast in the main plot with a professional and scripted sub-plot with a group of Armenian actors. In this, the film is a complex study of family, prejudice, and a piece that evokes an awe-inspiring romanticised image of Los Angeles as an overwhelming and complex city.

Conor: It’s so refreshing to see a lean, funny film that does everything it promises you it will do. It’s a delightful piece of escapism and education, and, at least on the face of the competition criteria (which are a confusing collection of platitudes no SFF jury really follows anymore), it is one of the more audacious offerings of the bunch. Not only is it well written and performed, the cinematography is arresting (ignore the iPhone hullaballoo, it’s good cinematography regardless of that factoid) and the loud, boisterous soundtrack keeps the energy well and truly going for the entire runtime.

Imogen: Tangerine was also one of my picks for the festival and one of my favourite films to simply sit back and watch. It’s uproariously funny while doing incredibly exciting things both in terms of representation and production. Baker apparently chose to shoot on iPhones in order not to intimidate his first time actors, and there’s a freshness and honesty that stems from this that is absolutely endearing. The characters are larger-than-life and unapologetically who they are, and it’s a total, entertaining delight to watch.

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl (dir. Alfonso Gomez-Rejon) – USA – Review

Imogen: Me and Earl and the Dying Girl fits strangely in the competition, and put alongside the rest of the titles, and in some cases, the issues and struggle they depict, it feels especially at odds. Following the journey of a Greg, a teenage boy in Pittsburgh who makes parody movies with his friend Earl and is forced to befriend Rachel, a girl diagnosed with leukemia, by his mother, it certainly doesn’t feel “audacious”. My biggest issue with the film is encapsulated in the title, which begins with “me”. The film’s depiction of Rachel’s journey through cancer is at times quite touching and moving, but it’s primary concern is with Greg’s journey towards hating himself less, and it uses Rachel’s cancer to do so. Gomez-Rejon and screenwriter Jesse Andrews set self-centred Greg at the centre of the narrative, and while showing us how self-absorbed he is, they never really rectify it – the film feels like it’s constantly setting itself up for his comeuppance, but never delivering it. Instead, Rachel’s illness becomes a stepping stone in his personal development, and she is rendered voiceless in the pursuit of his catharsis. Screening alongside films with innovative production, made by filmmakers who faced real risk for their craft, following maligned and persecuted groups of people, this can’t help but feel like a self-indulgent Sundance hit.

Conor: I pretty much just want to co-sign what you’ve written Imogen. That’s basically it, that this film has no place in the competition, but I’d go further and say it doesn’t have a place at the festival. A Sundance hit that’s guaranteed a theatrical release (good old ‘indie’ behemoth Fox Searchlight), it’s a well-made crowd-pleaser for sure but ultimately a hollow film about film, and friendship. It tries to use self-awareness to make up for its mostly mediocre variations on tropes but that’s really not enough to go by here, something made even more clear considering the film screened in between the parts of Arabian Nights, the eventual competition winner.

Jeremy: There’s not really much to add here. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is a film I’ve seen plenty of times. I feel that relying on familiar experiences and universal sadnesses to provoke emotion from an audience without having being aesthetically or cinematographically interesting, lacking any strong characterisation, whilst having a weak and clichéd plot is offensive to the viewer. I’m sure there’s good intention behind this film, but it definitely doesn’t convey it as well as it could have. When you’re dealing with such high emotion subject material, it’s really important to get it completely right.

Arabian Nights (dir. Miguel Gomes) – PORTUGAL – Review

Conor: What a glorious mess of a film. It almost seems unfair to have it play in the competition, considering its scope and mode of execution. Six hours over three films that all aim to paint a picture of Portugal under the crippling austerity measures imposed by its government is so unique, unexpected and amusing, but, unfortunately, it’s not all brilliant. I liked it a lot, all three films have some really strong moments, but it is uneven when taken as a whole, and its thesis of addressing the state of Portugal today is more salient in theory than practice. As a weird and wonderful cinematic experience, though, it does deliver, wildly jumping between genres and tone, from its longform sketch comedy in Part 1 to three short films in Part 2 to an unexpected mesh of fantastical narrative and droll documentary in Part 3.

I think that films that are this ambitious and that demand such a big investment from their viewers to actually experience a 6-hour film over two days (clashing with so many great films in the festival program on that final weekend as well) means that too often we either expect or lean towards it being this masterwork, treating it like any other film in the competition doesn’t seem to cut muster. I don’t think that’s entirely true, and whilst it really is an extraordinary concept, I don’t know if it entirely lives up to that premise. It’s still strong, though, at times utterly superb, and an oddly personal work that feels like a ever-expanding dare, with some of the best use of music in the entire festival – The Carpenters’ cover of “Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft” was particularly inspired. I’m glad it was in the competition, though, because it got a whole lot of people to seek out a film they might not have ever experienced had it not run as one of the twelve up for the prize. It’s win is a bold move from the jury and the festival, as it rewards a festival-only film; a theatrical release doesn’t look likely here in Australia, and so it will be the second Sydney Film Prize winner to never be seen by a wider audience after Yorgos Lanthimos’ Alps.

Imogen: Having only finished watching Arabian Nights yesterday, I feel like I’m not yet in a place to know how I feel about it, other than that on a broad scale I loved it. Its six hours are packed with characters, narratives, moments and stories that I think will slowly seep into me over the coming weeks, by which time I think I’ll have a better understanding or sense of what on earth Gomes did to me during those six hours. At this stage, I found the third chapter to be the weakest, and struggled through a lengthy episode about bird trapping – which is a shame, given the third chapter opened with a great sequence about Shehrezade herself and some fantastic vignettes about her encounters with people. Perhaps in a few weeks the birds will have grown on me – for now, I can heartily recommend the film and I earnestly hope that it finds some way to its audience, given the challenges inherent in distributing a six-hour epic parable about Portuguese austerity.

Jeremy: Arabian Nights is a film that probably had me reflecting on it for longer than anything else in the competition, and that alone is an impressive feat. Miguel Gomes’s attempt to navigate Portugal’s socioeconomic woes through a contemporary retelling of the Arabian Nights is fascinating in itself, however, the result is quite overwhelming. I might be in the minority here, but I don’t think the film is a mess or that any part of it is excessive. I feel that the sections that may feel unnecessary work incredibly well at enforcing how poignant and affecting the best scenes in the film are. The opening – which flips between a documentary about the docks in Portugal and about Gomes’s decision to make the film in the first place – is the perfect framing for the film; unsure of itself, political and clear in the vague goals it wants to achieve. From there, the first part had a bunch of comedic shorts that were solid for establishing the work, although in it there were some latent issues emerging in Gomes’s approach to humour that made several parts of the film less enjoyable than it could have been.

In its structure, scope and composition Arabian Nights is a masterpiece. However, several scenes fall to the lure of using racial or sexual tropes for humour, becoming unnecessary jokes that make their point through objectification and mocking of certain disadvantages. While Gomes clearly intends for his film to be a treatise for those affected by the great economic woes in Portugal today, using social hegemonies as short-hand for universality often feels a bit insulting to the audience he’s making those jokes for. If Gomes intended to make political points about racism and sexism in Portugal through the ‘black shaman figure’; racial slurs; sexual Orientalism; and an off-colour set of rape jokes, it failed. If the political satire cannot be built on the backs of those in power, rather than on the back of the clichés and stereotypes about the groups that these very points were being made for, then these trivial additions should have been left out. They detract from an otherwise masterful work.

The high points of Arabian Nights are some of the most phenomenal scenes at the festival; constantly diverse, insightful, and cutting critiques of Portugal. Gomes deals with romance and existential ennui in an astounding way, while the final scene – while it alienated a lot of the audience with its sheer length – was, for me, the most important of the film. It brought a friend of mine to tears, simply through the beauty of flow, composure and depth of the shots; the implications of the story as a conclusion; and the use of music in the most apt way. There’s so much of Arabian Nights that makes it one of the most incredible films in the Official Competition, but it’s something that should be appreciated critically. Having a 60+ year old man behind me laughing at the N-word being used (despite it being used in a serious manner) and the majority of the humour at the expensive of oppressed groups within Portugal made it clear that while I was able to take a lot from this film, it’s easy to understand how seeing this could have been a fairly difficult and confronting experience for other groups.

Rankings

| Conor Bateman | Jeremy Elphick | Imogen Gardam |

| 1. Tehran Taxi 2. The Daughter 3. Arabian Nights 4. Victoria 5. Tangerine 6. Sherpa 7. Tales 8. Black Souls 9. A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence 10. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl 11. Strangerland 12. Vincent |

1. Tangerine 2. Tehran Taxi 3. The Daughter 4. Arabian Nights 5. Tales 6. Sherpa 7. Victoria 8. Black Souls 9. A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence 10. Strangerland 11. Me, Earl and the Dying Girl 12. Vincent |

1. The Daughter 2. Victoria 3. Tehran Taxi 4. Arabian Nights 5. Tangerine 6. A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence 7. Sherpa 8. Strangerland 9. Black Souls 10. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl 11. Vincent |