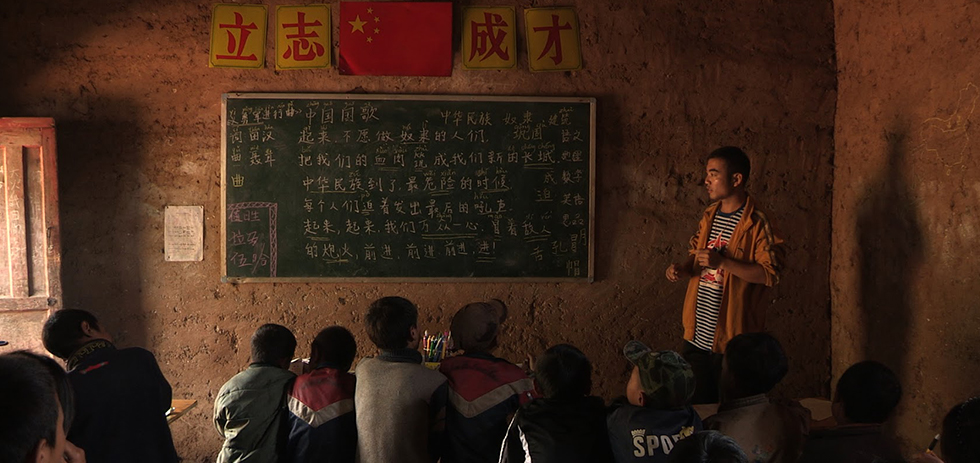

A Young Patriot is about this kind of maturing period for Zhao, as he’s moving out of a more ignorant and early stage of his life, to developing this broader view of China – what drew you to this story in particular?

As you know in 2008, there were a lot of major events that happened in China – the Olympics, the Sichuan earthquake. After that in 2009, the World Expo was held in Shanghai, and all of these things made the general public very excited and their confidence about the country becomes stronger and stronger. Especially the young people among the general public were excited, so I wanted to see how they see the country. So I was really lucky to have that encounter with Zhao on the streets of Shanxi, and he’s very brave to express what he thinks in his heart. He’s very energetic and driven by his activities.

The idea of consumerism in China seems to be another major idea in your work. 1428 has a particularly familiar scene-where recordings of the effects of the Sichuan earthquake are sold as tourist merchandise for the area. Do you intend to make documentaries with a political bent or does this emerge implicitly throughout your documentary-making process?

This was quite clear for me. I want to use this is as a film to observe the cause of young people; the way they grow and the way they chance. And also, this tells us about Chinese society, and also I plant a lot of my personal views at the same time.

I’m curious about your personal attachment to rural areas in China. 1428 looked at the Sichuan province, Umbrella looks at Henan, Zhejiang and Guangdong, and A Young Patriot is set in Shanxi. What draws you to such a wide variety of rural settings in your work?

Since I started shooting documentaries, I find that I’m very interested in the power that the documentary has. When you use documentary to describe a society you have a lot of space, you know you can talk about society, about minority groups, about animals, about environmental issues. So documentaries are a really interesting way to observe society.

Like I mentioned, through the documentary we see these changes in society and from 2000 I’ve been actively seeing a lot of problems in society. After 7-8 years, I accumulated a lot of materials about the current situations and the problems. Those situations and problems, I have my own personal views and judgements on them and while shooting them all of those attitudes and knowledge, I’m gathering information about them, and I’m realising that a lot of the problems and the roots of these issues come from the rural areas in China. There’s a huge gap between the urban and rural areas, and this gap was created as early as 1949, or earlier. The new government didn’t solve the problem, and the gap is widening. So a lot of the social problems actually come from the gap between the urban and rural areas, so personally, I was born and grew up in the city. I’ve never lived in the countryside, so I’m really interested in the stories from the countryside and I want to know a lot more about those things. With 1428 we shot in the city and in rural parts, but in post-production we cut the city parts to focus on the rural parts.

I was wondering about the name “Mr. Patriotic Maniac” – did the nickname wear off now that Zhao’s moved away from his early fervour or has it remained in Pingyao? Did the film cause controversy in China with this?

As you can see, there’s a huge change that has happened to Zhao. Initially he’s someone marching down the street, but now he’s become an angry young man. Currently, we haven’t been able to screen the film in China. We don’t know whether we would be able to do that, but we would like to try. At the moment, a lot of people from mainland China have seen the film in foreign film festivals and have tried to discuss it online – but they’ve been deleted. It seems they’re not even allowed the space or freedom to discuss online.

I feel your film is also very sympathetic towards this idea of patriotism, taking a lot of care to humanise Zhang – as a representation of a broader issue – as someone who is more a product of circumstance and influence, rather than inherently patriotic. That is, you put in a lot of effort to show why your subjects view things the way they do, and I think that’s a very important part of the documentary. Could you talk about why you take that approach?

I like to use a very direct approach to express and this also respects reality, for example, you can see the natural change and the growing process of Zhao throughout the film, but not a very subjective observation. The whole process is natural and there are not many forced changes for him and we’re trying very hard to have as less of an impact on him as possible. Of course, the shooting of the film had some impact on him, but it’s about trying to minimise that and we want the audience to think about this reality we show in the film.