Gaspar Noé’s explicit foray into sex and sentimentality carries with it a lot of expectations. Noé has built Love‘s media profile through controversy; he released numerous explicit press images and a number of graphic posters,1 he stated a hope that “guys will have erections and girls will get wet” when watching the film, that it would give guys “a hard on and make girls cry“, and even that he felt his explicit 3D sex odyssey was appropriate for pre-pubescent teens. While such statements may be good for press coverage, Noé is selling himself short; Love is a proficiently realised exploration of the rise and decline of a relationship told from the perspective of an arrogant, self-serving male lead who has never fully been able to grapple with his emotions, a personality flaw that leads to a number of indiscretions which he is (rightfully) punished for. While there was no need for the film to be shot in 3D (a gimmick that is clearly utilized only to afford Noé the opportunity to render a few money-shot gags), Love is aesthetically accomplished, a beautifully composed, rich, restrained production boasting more flair and a much more impressive colour palate than any other tale of romance in recent memory.

Love is filtered through the eyes of Murphy (Karl Glusman), a man in his late-20s/early-30s who fathers a 2-year-old infant, Gaspar, with Omi (Klara Kristin). The film takes place on New Year’s Day, following Murphy as he, hungover and depressed, drops ecstasy and reminisces about his lost love, Electra (Aomi Muyock), and the personal indiscretions that led to the crumbling of their relationship. His scattered recollections of their fragmented relationship travel back and forth across convergent timelines, as Noé messes with the film’s temporality as he has previously in earlier works Enter the Void and Irreversible. As a character, Murphy is unequivocally a bad human being; he is self-centred, arrogant, violent and occasionally even sociopathic. He cares only for himself, and his apparent sympathy for others is merely the result of a conceited effort to convince himself that he is a good person – it is no accident that Noé has rooted the entire story in the perspective of Murphy, a man unable to truly admit to his own deep-seated issues; as the film progresses, and as the depth of Murphy’s character flaws becomes more fully realised, he is increasingly used as a vessel to call out the more negative aspects of Noé’s audiences’ personalities.

One could write Love off as a ‘white-dude problems’ film, but doing so understates what Noé attempts here, ignoring the director’s thematic objectives and focusing purely on the film’s base narrative. One, too, could take issue with Noé’s gaze in his portrayal of sex, given that men are shown reaching climax far more often than the female characters – once again, this would be an unfair base reading of what Noé has given us; in fact, to allege that sex is portrayed through a traditional male gaze is arguably incorrect. Noé’s graphic portrayal of sex (for the most part) has a tenderness and sentimentality that in no way reflects the hypermasculinised portrayal of intercourse in hardcore pornography and the majority of mainstream cinema throughout history. One of the film’s stylistic highlights is Noé’s portrayal of sentimental sex; the actual portrayal of intercourse never feels exploitative and proficiently propels the narrative, effectively marking shifts in power balance and relationship dynamics as the coupling of Murphy and Electra progressively decays.

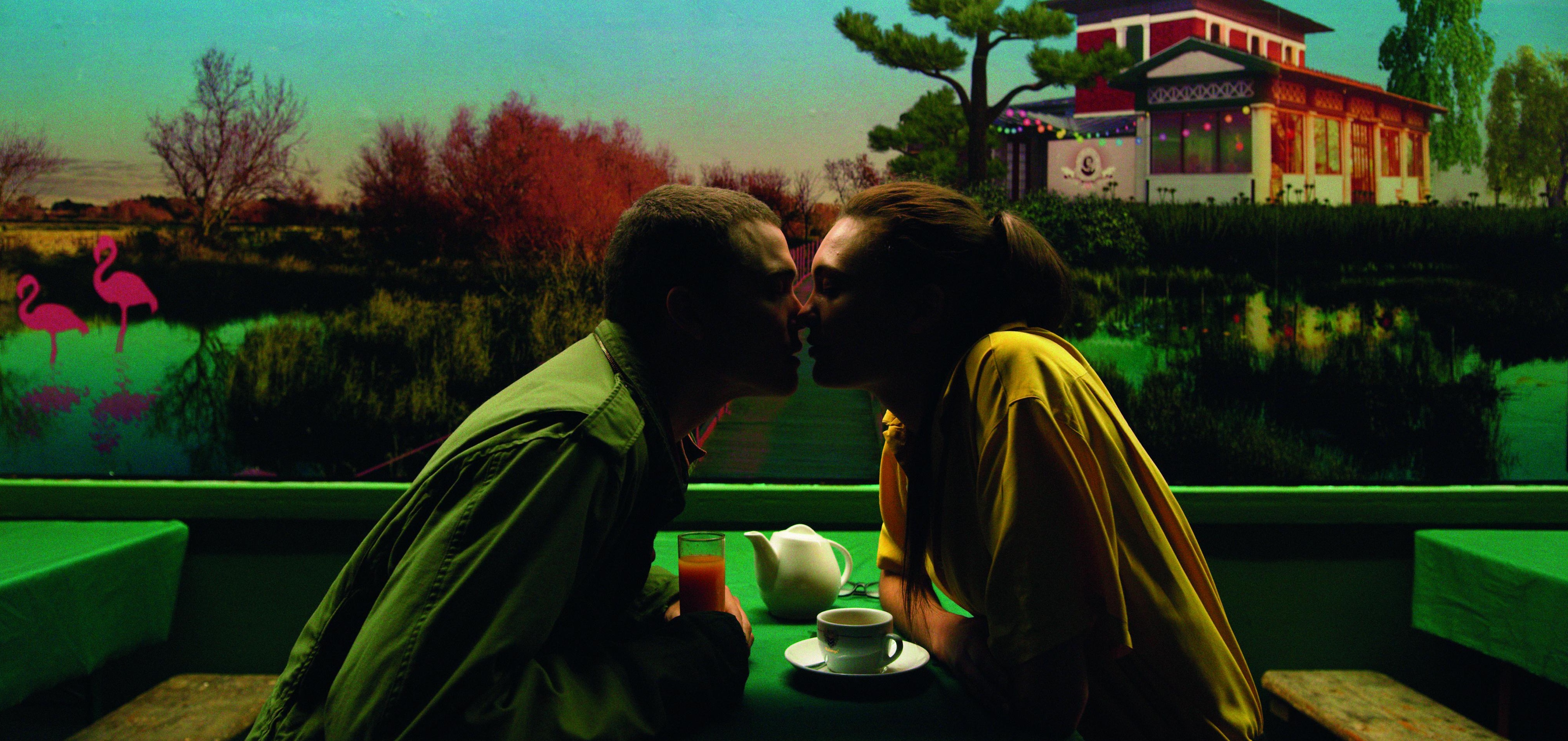

When it comes to pushing boundaries and making his audience feel uncomfortable through a cracked use of formal elements, Noé is king and his work Love, while far more toned down than that in I Stand Alone, Irreversible, or Enter The Void, is no exception. We see him break the 180 degree rule in an early threesome between Murphy, Electra, and Omi;2 his use of the track “School at Night” by Goblin, an aural reference to his short Eva and allusion to Dario Argento’s Deep Red, subverts romantic comedy tropes by unnervingly underscoring the scene in which Murphy impregnates Omi reaching its climax as he climaxes (and realises his condom has broken); on the flip side, Noé and regular collaborator Benoît Debie also expertly and effectively use colour and slow camera movements to convey the sensuality and sentimentality of tender moments throughout the film, manufacturing that warm and fuzzy feeling so many romance films fail to attain.

Given that he clearly wants to make his audience feel through more formal elements, is it much of a stretch to suggest he might wish to do the same on a narrative level, rooting his film in an unlikeable character that holds a mirror to the more uncomfortable personality traits of his audience? It’s clear that he wants to evoke a visceral response from the spectator through his use of gag shots portraying penises ejaculating on his audience in 3D, and his almost parodic level of self-referentiality – a gallery owner called Noé is played by Noé himself; a child is named Gaspar; shots, props and audio cues overtly reference sequences from earlier works for no particular reason. It seems unlikely to put the characterization of his lead down to incompetence, given the strong tonal shift at the film’s mid-point from simple sentimentality to a reflection on personal failure. In fact, as Murphy’s character becomes a reflection of our personal indiscretions the film gains its true power – Noé punishes us. It’s surely a vanity project, but Love offers far more than simple ego-stroking and pretentious moustache twirling.

That’s not to say that the film isn’t without problems – far from it. The lines fed to Noé’s non-professional cast and their performances leave a lot to be desired, as do the film’s final 20 or so minutes which, packed with fake endings, are frustrating to say the least.3 In addition, as the 3D is a totally redundant gimmick, only necessary for two visual gags and a 30-second throwback to Enter the Void, one can only think that the film might have benefitted from its exclusion. From a marketing perspective, while I do almost sympathise with his suggestion that Love is appropriate for 12 year olds, the whole campaign surrounding Love, with ejaculate-fuelled trailers and porno chic infused advertising materials, does come off as a little juvenile and is a total misrepresentation of Noé’s tender, nuanced feature. Despite all of this, I can’t help but adore Noé’s latest experiment. The film is a magnificent mess, biting off far more than it could (or should) chew, and fully knowing of it. There’s a wonderful, self-aware sloppiness to the final product, one which is at times genius and at others utter garbage – at least on a narrative level. Somehow, Love manages to maintain momentum for its 2h15m runtime, and although there’s a lot of fat that could probably be cut, it never really feels like it drags.

All in all, Love stands as a beautiful, sloppy mess of a film – a fully realised and (mostly) well-executed “feeling” movie that is held back by Noé’s own self-interest and arrogance (much like our protagonist). It truly is a unique beast, and Noé cannot be faulted for his proficiency in conveying its stated thesis – a narrative and formal exploration of sex and sentimentality through the medium of cinema.

Around the Staff

| Brad Mariano | |

| Lyndsey Geer | |

| Dominic Barlow | |