Putuparri and the Rainmakers, a new Australian documentary that premiered last week at the Melbourne International Film Festival, works quite effectively on two levels. In some ways it’s like two docos coexisting within the same 97-minute runtime – no surprise considering its convoluted 14-year production history.

The first “film,” the one you’ll read about in marketing synopses, chronicles a remote Aboriginal community’s fight for land rights, and the way they use art to rally support and teach outsiders about their culture. Cinematically speaking it’s more or less conventional. There are, for instance, some pretty cloying music cues, the bane of so many docos; and the trailer-ish montage that forms the first passage of the film is especially weak. But once the narrative gets into gear, the patience and skill employed by director Nicole Ma and her collaborators over years becomes apparent; and they tell a naturally uplifting story quite well. And given the threat to Aboriginal communities in Australia at the moment, it’s the kind of story that can’t get enough exposure. Overall the account is as plainspoken, honest and adroit as its subjects – especially because Ma lets them speak for themselves.

Interwoven with this documentary is another film entirely, a feverish and visionary meditation on the connection between landscape, culture and survival in the Great Sandy Desert in Western Australia. This film frequently abandons narrative, even if just for a few minutes, to revel in the shapes, colours and elemental forces of the desert world; and lets the sights and sounds of mythic and ritual life tell their own story. These are the most rewarding moments of Putuparri and the Rainmakers; and occurring as they do in patches amongst the larger whole, they seem as satisfying as the “living water” that the Wangakjunga elders dig from the desert sand.

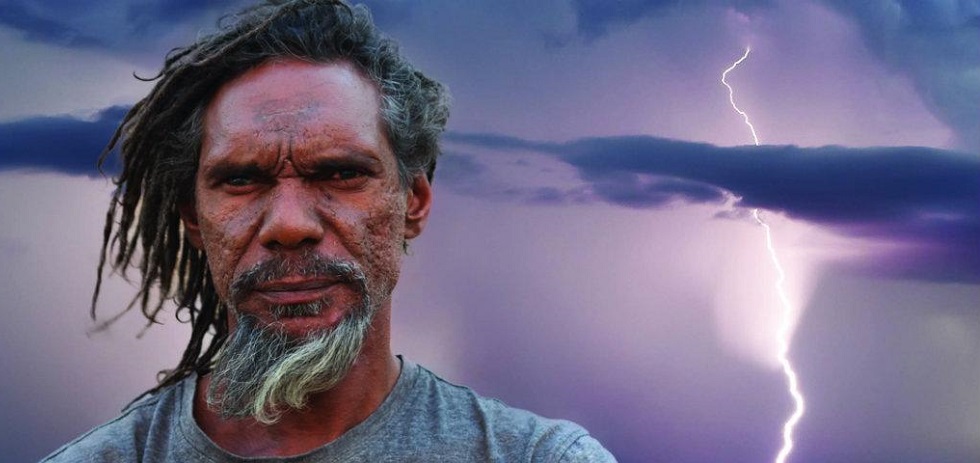

The film’s narrator and main subject is Putuparri, whose English name is Tom Lawford. The 42-year-old was raised in Fitzroy Crossing, a small, isolated town in the Kimberly where most of the Aboriginal residents work on cattle stations. His people were forced to leave their homelands in the Great Sandy Desert after whitefella cattle trails destroyed many of their precious and sacred watering holes. Because their traditional country is so inhospitable and remote (there are no roads leading there), the Wangakjunga have been especially in danger of being cut off from their way of life. Over the 20-year span of the narrative, Putuparri becomes a key figure in restoring his people’s connection to their culture, as he takes part in expeditions to their traditional lands, coordinates efforts for a Native Title claim and helps teach the ancient ways to the next generation.

Putuparri struggles to define his own identity in the chasm between his culture and the encroaching Western world (and perhaps the film’s aesthetic duality echoes that conflict). He got his start as an activist at a young age, and certain cues display his connection to global movements for human rights and black consciousness: he wears his hair in dreadlocks, and we glimpse an image of Bob Marley on his computer desktop. But the colonial disaster takes its toll; like so many others he’s plagued by poverty, unemployment and self-doubt. He also battles alcoholism; and in one unnerving passage, his grown daughters are frank about how he beat their mother. Ma gave Putuparri full say at all stages of editing, and it’s impressive that he allowed her to show some of his most disturbing or abusive traits; it makes the story of his transformation into a community leader more complex.

The other key figures in the film are Putuparri’s “grandfather” (as we would say, his great-uncle) Niyilpirr Ngalyaku “Spider” Snell, and Spider’s wife Jukuja “Dolly” Snell, both wizened Wangakjunga elders and truly remarkable people. It’s worth watching this film just to get to know a little about them. Spider is the custodian of Kurtal, the most sacred watering hole in their country, also the name of a snake spirit that brings rain to the region. He leads the rain dances that are central to the culture. Dolly has become a well-known artist; their country is the exclusive subject of her vividly hued paintings.1

In 1995, two years after the Native Title Act was passed, Spider led the first of a series of expeditions to Kurtal so that his people could begin claiming their land. The twentysomething Putuparri filmed the trip on VHS. That footage of a dangerous trek through the trackless desert and an astounding rain ceremony at the jila, the sacred watering hole, is the aesthetic and emotional heart of the film. The shaky, distorted, intensely colour-saturated analogue images are so hypnotic and haunting: the spinifex set on fire by Spider to alert Kurtal of their arrival, Spider chanting as the entire desert seems to burn around him, the smoke roiling against the sky and blocking out the merciless sun. The ceremony itself, with the elders digging at seemingly nothing until water bursts forth, encapsulated in their joyous song and laughter as they cover themselves with mud. The hair-raising moment when rain comes from nowhere. Through this VHS tape, the dreamtime exerts itself on the documentary’s narrative and on our consciousness.

In 2001, Ma was introduced to Spider; and soon was tasked with filming the half-dozen or so follow-up expeditions to Kurtal in the years since. This led to her collaboration with Putuparri, and hundreds of hours of footage documenting many other aspects of the Land Title claim, including the gigantic, stunningly beautiful painting of their country that Dolly and Spider and some 30 other collaborators did in 1996. It ended up touring prestigious galleries around Australia and raising awareness of their cause.

Ma admits that she had no idea what kind of film she was making at first. The years it took for this story to take shape, and the many difficulties of funding, logistics and permissions, lend Putuparri and the Rainmakers a meandering quality that’s sometimes distracting, but also appealingly loose and unstudied.

Later on in the project, Ma hired Paul Elliot as cinematographer. His gorgeous, high-def images, especially of the desert and the expeditions to Kurtal, are a terrific accompaniment to the lo-fi archival footage, greatly enhancing the dreamlike (dreamtimelike?) quality of the film’s superstratum. Even in more prosaic moments, Ma knows when to let go. There’s a thankful lack of talking heads, other than the engaging interviews with Putuparri and his family; hardly any whitefellas appear to whitesplain things. The rhythms of Wangakjunga speech, song and dance inform the editing flow; and there are quite a few pauses for quiet contemplation. These layered tones reflect the collaborative nature of the project, offering agreeable reminders of the films Rolf de Heer has made with Aboriginal collaborators (Ten Canoes, Charlie’s Country), as well as Werner Herzog’s drifting, rambling documentaries. These qualities make the overall reliance on conventional doco technique more bearable and justifiable, especially given the general audience this film’s story is aimed at. Putuparri and the Rainmakers is entirely worth your while.