“…if, as a science fiction writer, you ask me to make a prediction about the future, I would sum up my fear about the future in one word: boring.” — J.G. Ballard, Re/Search #8/9 (1984)

It’s a common observation in film criticism that the best screen adaptations of literature depart liberally from the source material, borrowing only what is necessary to reshape the text within a different medium. On these preliminary terms, Amy Smart and Ben Wheatley’s adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s 1975 novel High-Rise is a success. Smart’s script streamlines the narrative focus of the book while retaining much of its detail. The result is indebted to its source, but also standalone as a recognisable entry in the filmmaker duo’s growing oeuvre; a body of films which catalogue and recombine various genres from the last fifty years of British cinema. Unfortunately, what makes for an intriguing and promising premise has resulted in a disappointingly inert film. Similarly to their last feature, the underwhelming A Field in England (2013), the film’s tone is uneven and a handful of memorable images fail to cohere or contribute to a greater effect. While its visual and sonic re-imagining of late-’70s England opens up a range of interesting parallels between that period and our own, the depicted faux-transgressions are unexpectedly dull to watch, detracting from the many potentially fascinating details in its production.

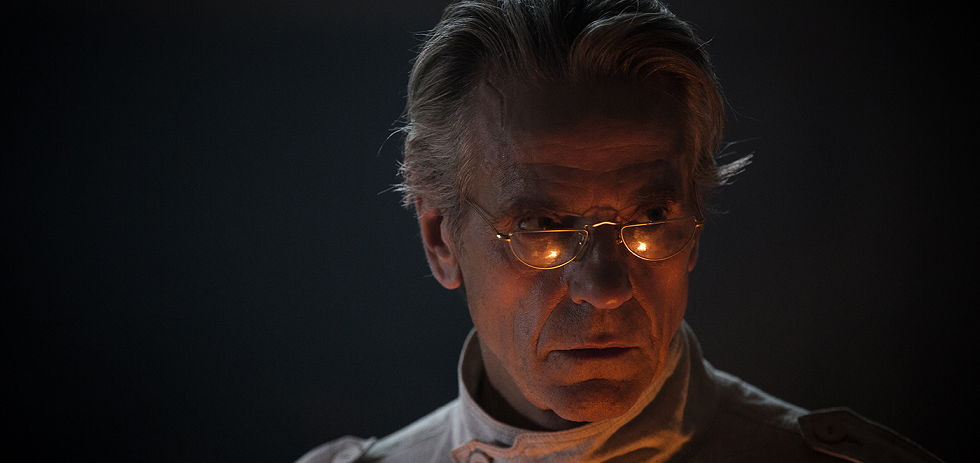

The film’s narrative is simple: it follows the gradual physical and social degeneration of a newly built high-rise building, filled with middle-class professionals. The building space is an environment sealed off from the rest of society, allowing the residents of its forty-odd floors to devolve into atavistic fantasy. Floors faction off into pseudo-classes, or tribes, and orgiastic revelry extends into untold hours, descending into sexual and physical debauchery. Dr. Robert Laing (Tom Hiddleston), the film’s protagonist, is a withdrawn loner who lives on the twenty-fifth floor and struggles psychologically with the death of his sister. The building’s architect, Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons), lives with his wife and other ruling-class fantasists at the top of the building. where they participate in an extended Ancien Régime party, complete with elaborate gardens and eighteenth century costumes. Richard Wilder (Luke Evans), a TV producer, lives on the lower levels with his wife (Elisabeth Moss) and children, and becomes obsessed with exposing the power structures of the high-rise in a documentary film. His brute physicality and short temper makes him something of a surrogate for the working class otherwise absent within the social strata of the building. Charlotte Melville (Sienna Miller) is a single mother who becomes the motivation for sexual conflict between the main male characters.

Crucially, for a story which relies heavily on the relationship between space and character, the visual and aural designs are the film’s greatest strengths. The high-rise decor, with its beiges and light pastel colours, and the residents’ immaculately observed hairstyles and costumes, anchor the viewer firmly in the ’70s without being a distraction. The film’s historical content feels alive precisely because it isn’t fetishised as a retro style. Instead, through oblique nods to future digital technologies and the origins of the incipient neoliberal government (the last shot features a Margaret Thatcher soundbyte extolling the virtue of free markets), the film implicates our own current situation within its dystopian vision. The soundtrack, too, is a particularly effective suture in the film’s many montage sequences and historical folds. Alongside Clint Mansell’s rich score is a set of incidental music consisting of artists like The Fall, Can, Amon Düül and most notably ABBA, whose song “SOS” is a motif first played by a string orchestra at a party and then later as a gloomy cover by Portishead.

However, for all the care put into designing the film’s architecture and setting, the ultimate effect of seeing its bare narrative unfold feels decidedly lacklustre, especially when compared to the energy of the book. The deeply oneiric and highly technologized worlds of Ballard’s novels evoke a brilliant volatility, where the latent savagery of humanity always threatens to erupt. This perverse psycho-geographical narrative space, the unmistakable tone which makes the novel ‘Ballardian’, doesn’t translate to the carefully assembled screen version. While arguing for the film’s independence from the source material is a legitimate defence for Wheatley’s film, it proves to be a much less interesting and provocative text than the novel. The gradual social degeneration of the high-rise is presented in a series of montages showing us loose parties, fights in supermarkets, random acts of violence in corridors and filmed public orgies, but the anticipated descent into some hellish transgression never arrives. The images of human destruction are simply boring.

The apogee of this tonal misfire occurs during an orgy scene on the top floor, among the ruling class tribe. Where the book depicts a genuinely unsettling devolution into primal sexuality, in which bourgeois relationships dissolve into tribal arrangements, the images of transgression in Wheatley’s film remain within the language of capitalist consumption. Its images are of a ho-hum swingfest orgy taken from a pornographic film played far too long. When its naked characters dance in slow motion and look into the camera, the film feels as though it were looking for an image powerful enough to signify pure abandon. Failing this, it is happy to luxuriate in itself, portraying a desperate party in the vein of any given music video.It may be argued that this is the point, that the film’s dulled tone is merely reproducing the flat affect and depthless subjectivity that typifies life within Western neoliberal society, but Ballard’s novel speaks more directly to the pathologies of the present than the contemporary film.1

Writing back in 1975, Ballard provides an uncannily prescient account of how twenty-first century subjectivity is pathologized into a depthless subject, atomised and networked within social media. Success in this world relies on the passive acceptance of a self which is comprehensively surveilled and quantified as data in an administered life of work and consumption. This theme is suggested during a brief monologue near the film’s end where Laing likens the building to a neurological system, hinting at burned-out synapses and an anhedonic drift where imagination and sexual transgression itself are entirely functional and commodified. Ultimately, the film may be consciously presenting this malaise and identifying its historical origins, but there is no need for more films which merely reflect on the dreadful tedium of Western life. High-Rise is a competent adaptation, but it exhibits a lifelessness unsettlingly close to Ballard’s worst dystopian pronouncement of late capitalism: its thorough boredom.

Around the Staff

| Megan Nash |