The titular “kiki” Sara Jordenö and Twiggy Pucci Garçon’s documentary denotes the youth-oriented subset of New York City’s ballroom circuit – a longstanding tradition in the African American and Latino LGBTQ community, immortalised in Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning (1990). “Kiki” is slang for having a good time with friends, and that’s the aim at the community balls put on by the kiki kids, which are part-fashion show, part-dance competition, part-party. The competing cliques within the scene (known as “houses”) bear names that playfully invoke the high fashion world; colourful epithets like The House of Unbothered Cartier and The Opulent House of P.U.C.C.I.

There are wild costumes, innumerable trophies, and plenty of voguing, but these balls are far from frivolous. The kiki scene doubles as a much-needed platform for education and queer advocacy. It is a safe haven for people who reside on the margins of mainstream society (often in terms of both racial and sexual identity), designed to provide youth with an alternative to the dominant, heteronormative culture quick to punish any sign of difference. The strength of the ballroom scene is a testament to the strength of its individual participants, all of whom have managed to channel the difficulties and prejudice they face into something that is creative and inspiring: a mode of expression that is by and for the (largely black and Latino) queer community, which remains underrepresented in the bulk of media (despite the increased visibility achieved through successful shows like Transparent, Orange is the New Black, and RuPaul’s Drag Race).

Kiki is comprised of loving and sensitive portraits of a handful of individuals who have found support and joy in the ballroom, and who in turn have helped others to do the same. Assembled together, these stories provide viewers with a window into this dynamic and vibrant scene, and like the scene itself, Kiki the film is a collaborative effort, made possible by the community it represents — an approach that runs counter to the burgeoning mainstream flirtation with queer aesthetics, denuded of its political roots. Director Sara Jordenö, a Swedish filmmaker and artist, developed the project in concert with Twiggy Pucci Garçon: kiki gatekeeper, community advocate, and founder of The House of P.U.C.C.I. Another layer of community involvement comes from the glitchy, pulsing score by Qween Beat, a collective of DJs and producers native to the ballroom scene.

Shot over four years, the film bears witness to a significant chunk of seven young people’s lives as they come into themselves and reflect on their hardships, their passions, and the relationship between the two. They speak about their experiences of homelessness, HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, prostitution, police harassment, and gender dysphoria – all issues of special relevance for those who identify as LGBTQ. Each person Jordenö documents is remarkably frank and articulate on camera, indicating not only the trust between filmmaker and subject, but also their mutual commitment to sharing these experiences. Kiki is a response to a lacuna in our cultural landscape: “I don’t see our story being told in history,” laments Twiggy. This absence of positive representation is a threat to the health and safety of LGBTQ youth, and a blockade on the path to a society that understands, protects, and celebrates diversity.

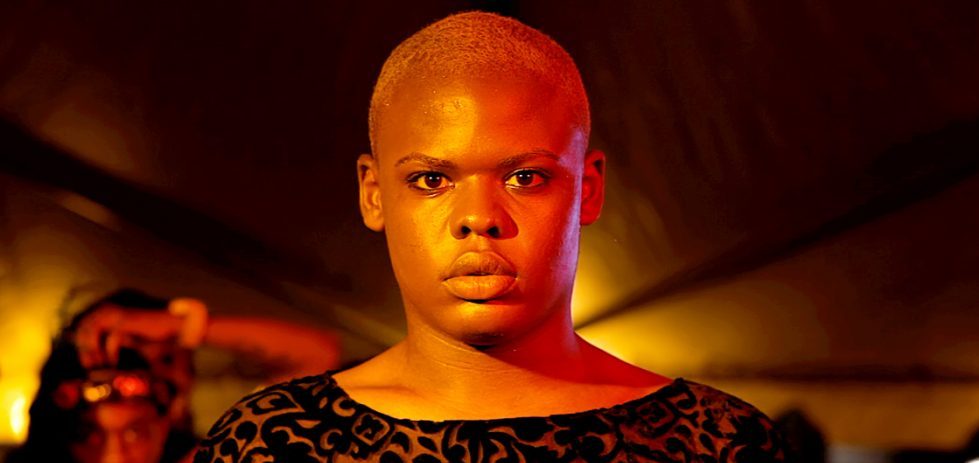

Repeatedly throughout the film, Jordenö’s protagonists are shown in close up, silently staring down the camera. These moments attempt to subvert the voyeurism inherent to cinema as the documentary’s subjects return and challenge the spectator’s gaze – a reminder of how the simple act of looking is rooted in the constructs of race, gender, and class. The question of who our culture grants subjectivity to is a political one. Kiki invites us into the lives of these individuals whilst calling attention to the imbalance of power that exists between the looker and the looked-at.1

Such interludes, with their comparative stillness, break up the high-energy sequences of the balls and ball rehearsals: the hubbub of the kiki crowd and the frenetic swagger of the performers. Balls are held in community centres, school halls, and gymnasiums, but the enthusiasm of participants transcends these distinctly non-glamorous settings. The atmosphere here is electric; infectious – thanks in no small part to the hypnotic combination of MikeQ and Qween Beat’s industrial, rapid-fire sound and the spoken-rapped commentary provided by tireless MCs who pace the ballroom floor.

Kiki manages to be both a lot of fun and very sobering; both inspirational and disheartening. Twenty-five years on from Paris is Burning, the ballroom scene it depicted is flourishing, but the community that gives it life is still under fire, often neglected or attacked both in the media and on the street, as is brutally evident in the wake of the Orlando shooting. Rupaul said, “as gay people, we get to choose our family,” and this film shows the truth in this, with its touching depiction of the strong, familial bonds within and between kiki houses. However, it remains a tragedy that in many cases these families are made up of people who have been abandoned by their biological family, or by their culture. There is a bittersweet quality to Kiki, with the strength and beauty of those in the scene always offset by the ignorance or fear of those outside it.

Around the Staff:

| Mei Chew | |

| Jessica Ellicott |