Ivo M. Ferreira is the director of Letters From War, which is in competition at this year’s Sydney Film Festival. His third feature, the film is set in Angola during the twilight years of the Portuguese Colonial War, making heavy use of personal letters sent home to his wife by the novelist António Lobos Antunes. We spoke with him during the festival about the process of writing the script, and how Portuguese cinema as a whole regards the country’s colonialism.

Welcome, thank you for sitting down with us. I wanted to start with the genesis of Letters From War — I understand that it is an adaptation of the writings of a very famous Portuguese novelist, António Lobos Antunes. Unfortunately, he’s not well known in Australia at all, so could you tell us a little bit about him?

So the film came from the letters he wrote in 1971. He was a doctor, and he was sent to Angola, to the “land at the end of the world” as it was called. During this period, ’71 to ’72, he wrote daily letters to his wife — before the war, they got married and his wife was pregnant. So he wrote love letters during this time, one, two a day, sometimes more, and these letters were kept by his wife over the years. When she was very sick in 2003 and 2004 — she knew she was about to die because she had cancer — she called her daughters and said “look I have this box of letters here, I’d be more than happy if you want to publish them once I’m dead.” So it started with this compilation of letters, published in 2004.

This was obviously very sensitive, not just because it was the biggest love of their lives, but because [the war] was a traumatising experience. I’m a friend of the family, and one day I came from Chile from a film festival and I arrived at about 6 in the morning. My wife, she was talking to someone in the house, and she was reading these letters to her belly — she was expecting a baby, she was 8 months pregnant. And also I had wanted to work on this colonial idea, but I never had an idea about how to grab the story. That’s where I thought “OK, maybe this can be the film.” That’s how it started.

So it sounds like you intended to do a film about that particular era, that particular part of Portuguese history, but these letters were the way in to making the film, in some sense.

Yes, this is… nobody talks about the war. There has been very little work published [on it], even books. It was a very traumatic experience. You have to understand that Portugal lived under fascism for almost 50 years, so this was the late years of fascism of course and after the revolution in 1974, the war stopped, the colonies stopped, and somehow the war and the colonies were sent to the garbage bin together with fascism.

I wanted to work on this subject, but I never figured out how. For example, something that I learned during this process was that nobody in the war talks about the war, as in the film. This is something that I learned over the process of research with soldiers that were actually there, and they are actually my characters [in the film] somehow.

Can you tell me a little about the research that you did? Obviously you were working with letters but I assume also that a lot of historical research went into the making of the film.

The basis is the letters, but then I had two novels from the author, the first two specifically talking about the war. So sometimes you can cross an episode that comes from the letter with how it happens in one of the novels. Also, the author writes chronicles for a magazine every two weeks.

Still?

Still. I also took these chronicles… for example, the episode with the very young girl in the film, I had three versions of that story: one from the letters, one in the chronicles remembering them otherwise, and a third in the book. So it was like a kind of puzzle to reconstruct the story. Of course I could choose whatever I wanted, but every time there was a version in the letters, that would be my north: I would choose the letters. If not, I’d choose something else. And of course, some military research, archives, and talking to these people, which as I told you was not very easy. In the beginning, not much happened, but slowly after a couple of hours they started to open up. It was very, very generous on their part and of course [the film is] for them.

One thing I was wondering when I was watching the film… I read a little about Antunes, and found out he wrote some novels about his experiences in Angola. But you’ve chosen to chiefly use the letters that he wrote there. What is it about that specific literary form that you like that drew you to them?

Well for me it was more fun to grab non-dramaturgic material, unorganised material that I organise myself, than to adapt one of his books. The two first books, Elephant Memory and Os Cos de Judas… the English title for that one by the way is The Land at the End of the World, and I know they were very far away. When I was filming, I was trying to get close to the places they were and it’s really far away from everything. Anyway, it looked more interesting to get the letters and to build my own script, rather than to adapt.

Well I guess in some ways the film does have a narrative, but it doesn’t move in quite the same way that it would if you had adapted a novel or something like that.

Yes, and as somehow there’s an energy, a… I don’t usually say this, or try to defend any idea [about it]… there’s something of truth in these letters. They are not fiction, he tells his wife whatever he wants. There’s an element of truth, and I think it’s also interesting to think that that was really written and the guy was really there.

I can imagine that one of the difficulties would have been in how to choose the letters that you were going to incorporate, because those decisions that you make reflect the type of history that you’re going to be making…

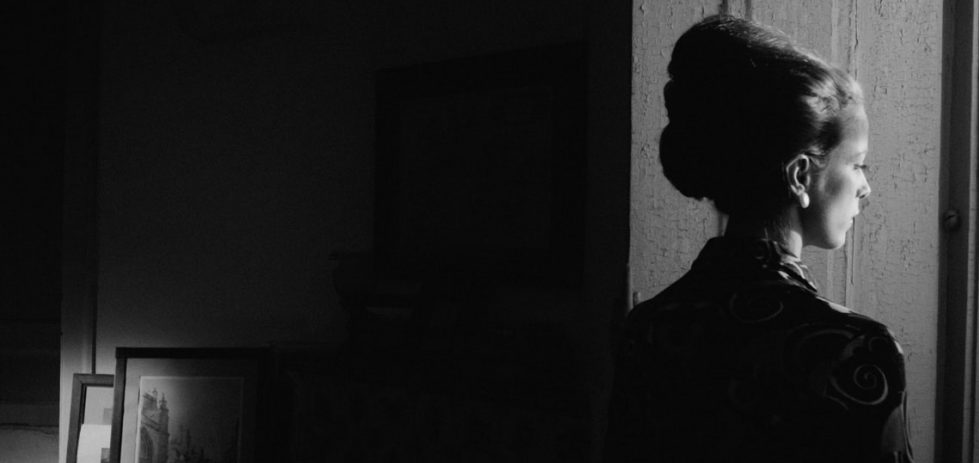

It’s a huge book. Yes, but first we chose letters for the script to try to explain to try to explain to the reader a little bit how it would work, because I said it’s not a film with voice-over, it’s a film with letters. And that’s why at the beginning it’s a bit heavy, so people get prepared for what’s coming, to give the key to the thing. Anyway, first we chose [the letters] for the script, and what looked so, so incredibly well done in the script didn’t make any sense [further] along the line in the editing process. Also, the choice of having her voice [lead actress, Margarida Vila-Nova, Ferreira’s wife] and not his [António’s] voice is something that was structural in the film. So we made this first choice, tried it a few times, recording it on a small recording device, then we edited, fine-tuned… we installed a kind of studio at home in the closet, and we re-recorded and re-recorded with different emotions and ideas, not just faster and slower, but also… and at the end we recorded everything again!

So things were changing a little bit and what was fun was to… there is a moment when you write a letter, there is time; remember, this was not email, it was small envelopes sent on a jet plane to a place and it goes off, etc. So the time to get to the reader, it’s already a décalage [interval] of several weeks. I wanted to work a little bit with this idea of time, so sometimes it has nothing to do with what we see. Because, also somehow the letters are an escape, a place where he protects himself. Sometimes when there’s a bad situation happening, we also have a beautiful letter that doesn’t relate to the image. Sometimes, like when the soldier loses his leg, it matches. He says “when father finds out, he’ll kill himself”. And then, a few seconds later we hear it in the letter. The idea was to try to get an organic structure that was not boring.

To me that was the most interesting thing about the film. You have a kind of structure that is created by sound, not by the images. I was also interested in how that changed the process of making the film. How did you think about the images that you wanted to put with the letters?

You mean from scratch or from the editing process? There were some letters that I always loved, that I was always going to include. The most clear example is the one where he keeps describing his wife and his love for her with all these adjectives – that’s the most iconic letter, I think. Many of them were present. As I told you, people don’t talk about war, so there were one or two things that I used from the letters, like even when he changes a little bit… when he goes off to war, he was an intellectual, and he was worried about this James Joyce portrait [that he had] on the shelf. And [Lunes] said to me, “Oh make sure that you put the portrait of James Joyce [in the film].” So he was not really into politics [at first] or viewing this war as it was.

Was he conscripted? I know at the time that conscription was introduced in Portugal…

If he could choose he would never have gone! Nobody would have, only a couple of crazy types. But anyway… About the images I was choosing, there were some episodes that are recounted in the letters that I reconstructed, and also from the novels. I wrote some scenes that were… For example, when they attack the village, the massacre of the village. In the letters, it’s a little little thing, but-

-but then you have to find an image for it as well.

Yes. I have to figure out how it should look. Of course, it’s always my vision of the war, it’s not a documentary of how the war was, but it’s very interesting that looking to the cameramen and the soldiers that were there, they said “You weren’t there, you weren’t born, how can you know exactly how our lives were?” I don’t know, I just figure it out. Of course, you have the iconography: pictures, photographs, much more than motion pictures taken by people that were in the war. People were there, they took pictures of course, but usually they take pictures of happy events… like once I was making a film, and my producer said “Let’s make a Making Of” — so of course at the end of the day all we had was footage of people eating and on the weekend and on days off! But, yes there were some good pictures that helped me to build my own vision of that world.

I watched one of your previous short films, The Foreigner, and you also use the letter format in that as well. Is that just by chance or are there any other filmmakers that you’ve seen do that and that you’re interested in?

It’s two films that have letters and voice over, but yes, it’s an interesting question… if I have more films that I like that have letters? I don’t know.

It made me think of Chris Marker.

Yes, I love Chris Marker. But then I don’t think about films when I’m making my films or writing my projects. I get more inspired maybe by dance than cinema. I do like movies! But I don’t think in films when I’m making my own. I have a friend who’s a director, he’s filming now. Everything he sees, he sees it in terms of a scene in another film. And I think, “Man, how can you film if everything makes you think of something else!” How can you film? I would just fucking stop and go home!

We were talking a little bit earlier about finding the images for the film, and I guess one of the most striking elements of the film visually speaking is the fact that it is in black and white. Why this decision? Sorry if that’s a question that you’ve been posed before!

Oh yes it’s a mandatory question…

Sorry, I really was interested!

Well the first reason of course comes from the iconographic material I had. And also, when you think about war you think about Magnum Photos… what I wanted to bring from that was what I discussed with the DOP, more the kind of lenses we use, a bit like some of the lenses that were used in that time. But the main reason was not to make a black and white because at the time movies and TV were black and white; I did it because I was really afraid of making a film about a very well known writer. This man was nominated 9 times for a Nobel prize for literature, he’s a very strong character, he has a very strong character, and he’s very well known publicly. I know the family, I know the baby that was born [in the film], it’s my friend, the one who authorised me to do the adaptation of the book. The first time I called her I was in Germany for the Berlinnale where they were showing my previous feature film. I asked one of the daughter if I could ever adapt [this material]. She sad “No Ivo, never, c’mon. Never!” Even the idea of the image of the father and of the mother… they are even describing sexual relations. But then I tried to convince the two sisters…

So I was very involved with family, and this is Antunes’ story, so this was getting very heavy to me. And then I just, before starting shooting, maybe for the first day, I said” maybe we could do this in black and white”. I need kind of a filter to separate this story…

…some kind of distance.

Yes precisely, some distance. This is my film, not some António Lobos Antunes film, this is not a colonial war [film]. Because I was always afraid of how… everybody was like “Oh be careful what scenes… the problems you might have, the way you gonna portray this.” And I thought it’s my film, it’s not so much about the war, I don’t care! Of course I want actors that can hold a gun and not look like a puppet. Of course, when we tried the first few takes with the commands being given to the actors – first time it was a complete disaster, people falling down everywhere! But we tried 30, 40 times and then they knew what to do. It’s my idea of the war, and that helped me a lot to make a distance, to clarify what it was I was making.

When I saw the film, it made me think of these ideas of distance on a number of different levels: between you and the letters, which are something that belong to history, they’re not just a kind of reproduction from history, but actually belong to history. And then the images are another kind of filter. They’re not as immediate. They’re not the kind of images you always see.

You know, I like this. I never thought before about doing period [filmmaking]. But now I like it more and more, because somehow we all dress in Zara, and our houses are full of IKEA, and we’re more and more the same. And I don’t want that in my films. I don’t want to be too close to soap opera, the news. So maybe now I will be making more period… when I say period it could be 1990! And also the crew, they get much more excited when I give them lots of trouble, headaches! And more money to spend… it’s a problem! But it’s a problem that creates a good thing, because everybody’s focused on something in a different way.

I’m not an expert on Portuguese cinema in any way, but it seems like recently there are a few filmmakers from Portugal that are making films about this period-

-like what? Tabu?

Well yes, Tabu… well, maybe not about this exact period, but about Portuguese colonialism more broadly. Pedro Costa as well, maybe not as directly as you, but his films seem to be about the effects of colonialism…

Yes, actually one of the references I gave to my actors was… have you seen Pedro Costa?

Mmhm.

Do you know the the scene in the lift?

Yeah, in Horse Money.

What I gave to my actors was this experience like… we have all this idea of “oh the guards, the army etc”… actually there’s an amazing film, the only one in colour, it’s in 16mm, it’s French – if you google it, it’s easy to find. It’s these French/Belgian guys that go to Guinea, they go to film a reportage, and there is a land mine, and a guy loses a leg, and they are there and they film. And it’s really amazing, the faces are just… like, something happens. You have to watch it. And that scene in the film, when the guy loses the leg, when he keeps talking about shadows – it’s exactly what Pedro uses in Horse Money in the scene on the lift. So the reference I gave to my actors was that scene. And I think that Pedro Costa… it’s a marvelous film, and it’s amazing what he says about the war and this idea of you know, the end of the empire. It’s amazing.

I actually thought of that Manoel de Oliveira film.

“Non“?1

Yeah “Non”.

These guys, they hate “Non”.

Really?

The military guys hate it. Because people think that cinema is life. They don’t understand that cinema is something… Because in Non there’s a scene when they’re on a truck, and they talk about the war and philosophise. And people said “Don’t do like Oliveira did, making people talk about war during the war. That’s the most stupid thing! We never talked about war during the war!” And I said, that’s a movie, it doesn’t have to be realist. And I didn’t do it! So you’re saying that there are some directors, yes, but there’s a big lack of work about this period. With the trauma that this created and still has… I mean, there’s Margarida Cardoso and the film shot in Mozambique.2 There are some things, but still for the importance that this period had in the country’s history, it’s nothing, it’s ridiculous. And finally people are talking, more than forty years later.

Is it better represented elsewhere, say in literature? The other arts?

Not really. Recently, in the last few years, a couple of writers have written novels about this time and the time after the revolution and the people that left Africa after and went to Portugal, running away from their homes. Some of them were very wealthy and they came to Portugal and they had nothing, no house. So this was recently treated also in a novel. But still, it’s nothing for the size of our trauma, it’s nothing. There is something very different, when I’m talking about distance and all that. You have to understand that it’s about people that are still alive.

Yeah I guess it’s really not that long ago.

I know the girl… it’s very private. It’s a book that was published, not just letters, but still they are alive. This is what changes everything, and for the good. And also I think now that this generation is getting old and they never even talked to their wives about the war and what happened, maybe they think this is the time to talk. Now or never.