“He’s the last auteur that hasn’t sold out,” says Iggy Pop, sitting lank-haired at an interview table at Cannes. He’s talking here of Jim Jarmusch, who he shambled coquettishly up to back in 2008 with the idea of making a documentary about his proto-punk band The Stooges, five years after the reunion no one had been counting on. The pair had worked together before, with the Fun House singer showing up as a cross-dressing fur-trader in Dead Man and alongside Tom Waits in Jarmusch’s diner-and-social-awkwardness vignette series Coffee and Cigarettes’. Mutual admiration notwithstanding, it’s an uncommon origin tale for a documentary—a tribute by commission from the living subject to a director who has called the Stooges “the greatest rock and roll band, for me, ever”. Indeed, Jarmusch has said he prefers the description of “love letter” to doco. 1But‚ aside from the fact Iggy’s assessment of modern auteurism is patently untrue, the transmutation of primal rock to the silver screen by way of a suave arthouse director results in a love letter all too clean, and all too crisply sealed. It stinks of rose petals when it should be stinking blood.

I’ll get this out of the way first though. I liked Gimme Danger. I liked it for all its tragi-romantic betrayals and flaws, and despite the criminality of the cinema I saw it in playing the audio at least 50 decibels shy of acceptable. I couldn’t help but like it, because I couldn’t help but like Iggy, whose growlingly good-natured iconoclasm and self-deprecatingly wry recollections occupies most of the screentime. Rubbing a leathery foot with one hand, sometimes on a plush, gilded throne of a chair, sometimes next to a pile of dirty clothes, he delivers line after line of unmatchable anecdote—from his decision to become a singer because he was sick of looking at everyone’s butt as a drummer, to the time he bought a massive weed plant (roots and all) and cured it in a coin-laundry washer. It’s not all youth and debauchery though—he also uses the space to speak candidly on a few matters of music’s sociopolitical history. For example: that the flower power era was a government-funded citizen passivity program, and that the category of ‘Nihilist’ the media gave the band is risible. Iggy just wanted to be his own Stooge, and nobody else’s.

Though Jarmusch is adamant that the film is about Iggy and The Stooges—“if I were to make a documentary about Iggy, it would be about 15 hours long,” he declared—the rest of the band members are very much minor characters. When Ronnie Asheton, Scott Asheton and James Williamson, as well as a few others from the heyday do pop up, they lend their own memories, character and humour. The Asheton’s sister Kathy remembers feeling mostly relief when the band split apart (that her brothers were still alive was, to her, miraculous), and Williamson casually fills us in on how he went from almost violating a guitar in front of thousands to becoming Sony’s Vice President of Electrical Standards.2For anyone unfamiliar with the band, you’d think their history was predominantly made up of a baffling series of picaresque high jinks, a drug-fuelled boys-own misadventure arranged in jump-start chronicles.

It’s what makes it enjoyable; it’s what softens the sinews that should be ripped tight. Where was Iggy barfing onto the front row of a crowd? Where was the performative, impulsive self-mutilation on-stage, the confronting showmanship of anger and pain? Where was the brutality, the intergroup tensions, the broken years and broken bodies? Where was, y’know, the punk? Not in the swollen Chiller imitation font used to introduce the talking heads: this much will I say. To be fair, Jarmusch’s subjects were a significantly more mellowed-out bunch, but also a progressively diminishing one. Cobbled together in fits and starts between Only Lovers Left Alive and Paterson, it took seven years for Gimme Danger to see its fruition: years which would claim the lives of all interviewed band members but Iggy. Maintaining a critical distance with all those elegiac tones seeping inevitably in would’ve been difficult.

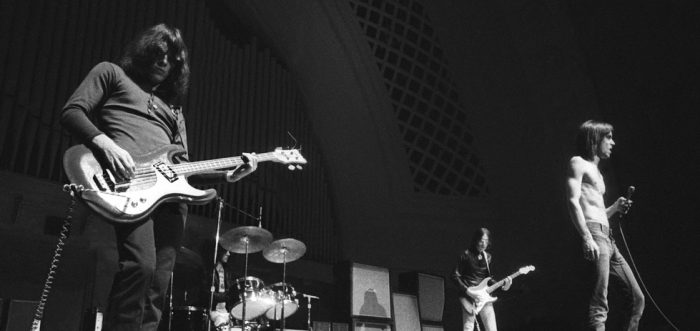

It’s true also that even if Jarmusch had wanted to show footage of, say, Iggy pulling his dick out and resting it on top of a speaker, he might not have been able to. When the band fell apart in ’74—the Asheton brothers turning tail for home and Iggy filled with more drugs than Trainspotting—they were spat out of music along with trailing columns of critical contempt, god-awful bootlegs, three failed records, and piss-all hope for any kind of legacy. More likely to be glassed by scandalised bikies than given the time of day by any cameraman, there’s scant footage from the band’s first tours – just a few images of Iggy’s sinewy body wriggling about onstage, launching itself into crowds, and outthrusting its magnificently firm buttocks in a primitive man’s crouching strut.

This absence turned out to be something of a boon for the director though; putting a licence stamp on alternative methods of representation. Filling up the space between the new interviews and archival scraps are inventive cutaways: from the playful animation by James Kerr (a.k.a Scorpion Dagger, better known for his Tate Gallery-recognised tumblr of Renaissance GIF remixes)3, to both iconic and never-before-seen photographs, to stock clips from TV shows and films of the era featuring the likes of Marlon Brando, Elvis and Lucille Ball—some with more meaningful lines of connection than others. It brings to the film the charm of a YouTube video made by an excitable adolescent, and though the cultivated immaturity sometimes feels gauche, it’s mainly a delight. When Iggy’s scorn for wannabe Dylans was matched with a photo of the crooner and a speech bubbled “blah blah blah blah blah blah”, I guffawed. It takes a certain kind of courage to be that level scrappy with a film so shamelessly hagiographic.

Though trading in viscerality and roughness for (relative) innocence and nostalgia, Jarmusch has given us—and Iggy—a gift, which, though pretty kitsch in its conventional ‘mad rock band crashes, burns, heroically reunites years later (cue: feelings)’ arc, is far too genuine to elicit scorn. I’d watch it again, if only to relive Iggy chuckling at what he said to Tony Defries in the back of a car, and to crack a deep respect grin for the way he says “cool”.

Gimme Danger is screening at the ACMI in Melbourne from 27 December to 18 January.

Around the Staff

| Luke Goodsell | |

| Jaymes Durante |