Written by Conor Bateman and Jeremy Elphick.

Sydney Film Festival has announced the first retrospective program for the 2017 festival and, much like last year, it’s a disappointment. To be clear, it’s disappointing less as a result of the chosen filmmaker than the fact the festival has persisted with the same approach to their major retrospective that they took in 2015 and 2016.

Selected and to be introduced by David Stratton, this year’s Essential Kurosawa retrospective is another partnership between SFF, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Melbourne and the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) in Canberra.1 Whilst this partnership reflects the current financial pressures of major Australian film festivals, it renders the SFF retro merely a travelling screening series, rather than an exclusive, event-specific program.2

Since 2015 the main retrospective programming at SFF has been a single-director series programmed by Stratton bearing the ‘Essential’ title, with Ingmar Bergman in 2015 and Martin Scorsese last year. Though SFF has had a recent history of single-director retrospective programming, with Douglas Sirk in 2011, Bernardo Bertolucci in 2012 and Robert Altman in 2014, this continued focus on the ‘essential’ works of an already canonised auteur reaffirms the festival’s move away from more playful (and more interesting) retrospective fare, like 2013’s series of British noir films and 2010’s vampire-themed series programmed by Richard Kuipers.

Akira Kurosawa’s relationship with Sydney Film Festival is a significant one. Sixteen of his features have been shown at the festival since 1959 (when Throne of Blood played), making him one of the most screened filmmakers in festival history.3 The selection of Kurosawa for the 2017 retrospective appears to bear no conscious relationship to this history, though, something particularly egregious when considering that the festival has already had a Kurosawa retrospective, billed as a ‘Special Tribute’, in 1971. That year’s festival, which screened Kurosawa’s then-latest Dodes’ka-den also presented some of his “lesser known works”, which were as follows: Sanshiro Sugata, No Regrets for Our Youth, The Idiot, Chronicle of a Living Being/I Live in Fear, The Bad Sleep Well, Sanjuro and High and Low.

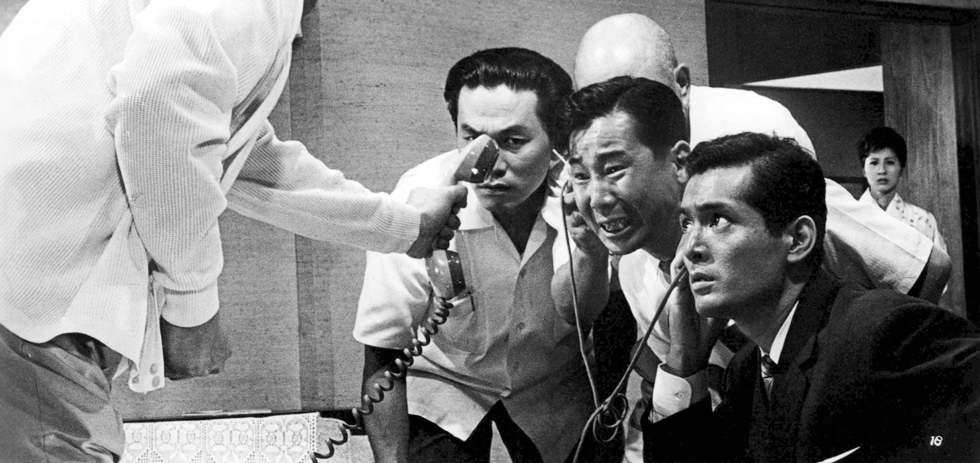

The ten films selected for this year are all relatively well known amongst the breadth of Kurosawa’s work. Only one-film overlaps with the 1971 series: Kurosawa’s 1963 thriller High and Low, which has since become one of his best known works, having been one of the first released on Blu-Ray in America. Of the ten, seven will be screening on 35mm film at the Art Gallery of New South Wales: Ikiru, Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, The Hidden Fortress, Yojimbo, High and Low and Red Beard. Three additional films will screen on DCP at Dendy Opera Quays: Rashōmon, Kagemusha and Ran.4

There’s less of Kurosawa’s breadth on display here than in the 1971 program; his epic jidaigeki adventure works (Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, The Hidden Fortress, Yojimbo, Rashōmon, Kagemusha and Ran) take centre stage and his slower, existentially-driven films have been omitted, save for Ikiru and, to some extent, High and Low. Both of these films, though, still remain part of the core canon of Kurosawa’s output: widely released and relatively available. Red Beard is likely to be the deepest cut in the selection, and arguably one of the most rewarding of the ten films.

A more comprehensive summary of Kurosawa’s work would have to address his earlier films. Perhaps this could have been achieved through the inclusion of a series of films he made starring Toshiro Mifune: Drunken Angel, The Quiet Duel and Stray Dog. His relatively direct adaptations of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot and Maxim Gorky’s play The Lower Depths would have been welcome as more obscure picks, while Dreams or Madadayo would have been a more effective portrait of the director’s late work than Ran.

The programming of a Kurosawa retrospective this year raises questions about the purpose of retrospective programming in Australian film festivals. In 2016, the Melbourne International Film Festival presented a program of films starring Japanese actress Setsuko Hara, who passed away at the end of 2015. In the same year, the Brisbane Asia Pacific Film Festival (which, sadly, will not continue in 2017) presented a retrospective series on three Japanese actresses of the same era: Hara, Kinuyo Tanaka, and Hideko Takamine. With both MIFF and BAPFF’s retrospectives drawing attention to the role of women in the golden era of post-war Japanese cinema, with the latter program simultaneously highlighting works from Kenji Mizoguchi and Mikio Naruse, it feels a bit lacking for Sydney Film Festival to announce a retrospective on Japan’s most well-known and celebrated filmmaker without any particular reason for doing so.

It is becoming more clear with each year that SFF are are taking a safe path when it comes to retrospectives, selecting canonised directors and some of their most famous films, rather than challenging audiences or pushing for a broad re-evaluation of a movement or era. As always, though, the major retrospective is not the only retrospective at SFF, and we hope that the announcements coming in May showcase a greater leap of faith.

You can read our coverage of the first SFF teaser announcement here.

Disclosure: Conor Bateman was part of the Film Advisory Panel for Sydney Film Festival in 2017. He did not advise on any retrospective films for inclusion in this year’s festival.