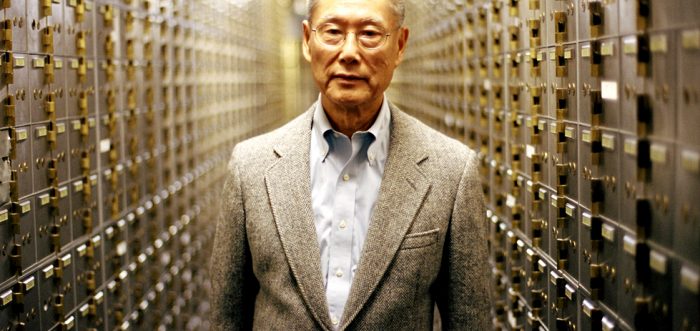

Thomas Sung, a former attorney and founder of Abacus Federal Savings Bank in New York, sits down with his wife Hwei Lin to watch Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life. “That’s why I started banking,” he says, pointing at Jimmy Stewart with a chirpy enthusiasm. Sung fancies himself as Stewart’s George Bailey, a down-to-earth community servant and family man. Yet for all his efforts to service his oft-overlooked Chinese community, Sung, like Bailey, has become a patsy to a system rigged against him.

‘Too big to fail’ is the colloquialism used in reference to the banks that avoided criminal charges following the 2008 financial crisis – ‘small enough to jail’ is the inversion. Abacus, the 2531st largest bank in the US, is the only one to have been criminally charged in relation to the 2008 crisis. They were charged with conspiracy to sell fraudulent mortgages to the Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”), despite uncertain evidence and their exceptionally low delinquency rate. They were scapegoats for a system that protects the powerful. Without saying so in as many words, Abacus: Small Enough to Jail tells a story about institutional racism – and a largely compelling one at that.

With the exception of the intimate biographical documentary Life Itself, director Steve James has made a career out of focalised stories of broad, often systematic issues. He does much of the same here, shedding light on the GFC backlash by telling the story of a family business who readily dealt with any issues of fraud going on inside their doors. The Abacus bank is these days run by Thomas’ daughter Jill, with the help of two of her sisters, all of whom double as lawyers. “Although this is David versus Goliath… they’re a whole family of lawyers,” one commentator explains. What makes Abacus so effective,though, is not its political agenda, or even the curious litigation surrounding the Abacus bank, rather it’s in the examination of the inner-workings of a family and a community.

It’s not by chance that the Sung family make for great subjects. The things that make families interesting are the nuances of their relationships, but those aren’t always easy to identify. James works hard to establish a rapport with his subjects so that they feel comfortable revealing themselves. They’re a highly educated bunch but are prone to the same inter-personal problems many of us face: a penchant for arguing over one-another, the inadequacy complex of the youngest child, the struggles of caring for an aging parent, and so on. These private moments are the strongest of the film because they serve to personalise a story that’s otherwise quite parochial, offsetting some of the dense courtroom moments peppered throughout.1

Impassioned journalists and interviewees say that they had never seen anything like the mistreatment of the Abacus employees. When the charges were laid, the bank’s staff were paraded out of their office as a chain gang, in a fashion which one journalist describes as “Stalinist”. The Sung family saw the charges as an insult to their Chinatown community and fought the case for five years, costing them around $10 million in legal fees. In what is one of the film’s most complex and interesting images, Thomas has his hair cut in a dingy Chinatown barber sometime during court proceedings and the staff thank him zealously for fighting on their behalf. That a barber would feel solidarity with a wealthy banker says a lot about a distinct feeling of against-the-odds unanimity among the community.

Thomas Sung aspires to be George Bailey the community servant, but what Abacus reminds us of is that the Sungs are working in a system that isn’t made to accommodate them – or, at the very least, that sees them as cannon fodder in large scale PR battles. Oddly enough, a story geared around the malpractice of multinational banks and large scale government prejudice is a minor work by James’ standards – but that feels like it’s for the best. James presents a story of banking misconduct to Trojan Horse in an acutely observed portrait of the lives of first and second generation Chinese immigrants, subjects who otherwise don’t see much in the way of Hollywood limelight.