Over the last decade, there has been a resurgence in Indian cinema of stories distinctly rooted in a sense of place. And these places aren’t the faraway Swiss Alps or the picturesque New York Bridge you might find on the canvas of a larger-than-life Karan Johar film. These places are closer to home – the smaller towns and regions of India itself, each rooted in a distinct sense of place and cultural ethos. As Shubhashish Bhutiani, the director of Hotel Salvation (Mukti Bhawan) told us here in Sydney, small towns have once again become vogue in Indian cinema: “we are finally telling stories from our towns, our cities and our problems”.

Of course, representing the aspirations and ethos of small town India on screen is not an altogether new proposition. In the Golden Age of mainstream Hindi cinema years, the setting would often be an unwritten influence on the film. It played a significant role in how the characters interacted with each other on screen and influenced their language and behaviour patterns.1. By the time the 1990s came, India had discarded its dreams of a Nehruvian socialist utopia and embraced capitalism with open arms.

This seismic shift in economic mindset also brought with it a shift in cinematic representation. The Indian middle class dreamt bigger than ever and was more aspirational than ever before. The dreams of a small town protagonist intending to ‘make it’ in the big city gave way to foreign locales and chiffon sarees of Yash Raj Films. Shah Rukh Khan taught a whole generation growing up in the ‘90s to embrace modernisation and westernisation with open arms, without relinquishing your Indianness. Suddenly, the small town sensibility was just that: small. The big screen had no space for it.2

Because of this, a whole generation of middle-class Indians growing up in the ‘90s (myself included), didn’t see much of their everyday life and its sensibility represented in mainstream cinema. However, through films like Rajat Kapoor’s Ankhon Dekhi (2013) and Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan (2015), this started to change. Bhutiani’s Hotel Salvation is another step in this direction. It is a multi-generational allegory of an India caught between embracing its newfound modernisation and liberalism while staying true to its Indian roots, embodied in the backdrop of Varanasi.

Upon realising that his time has come, an elderly man (Lalit Behl) takes his son (Adil Hussain) with him to check into a hotel in Varanasi where people go to die in order to attain salvation. Once there, he decides that he might not want to die after all. Bhutiani draws you into this world and its characters – which seem so alien at first instance – by punctuating the dramatic beats of the narrative, rather than playing up the humour embedded in the absurdity of the premise. By opting this more difficult route, and not going for the easy superficial laughter, Bhutiani establishes at the outset he is in complete control of the material at hand.

The setting of the film in the holy city of Varanasi is vital. The place is unlike any other in the world – where spiritual, religious and geographical ecosystems converge and meet. The broader relevance of the setting allows Bhutiani to layer his allegory: Varanasi is where the various belief systems and ways of thinking come together and meet at one place and consequently, the one place where the many pluralities of Indias – the small towns, the big cities, the upper class, the middle class – come together, if only for a moment in time. The director of photography, Mike McSweeney, presents this city as a complex and self-contained ecosystem, a difficult task to say the least, giving us ample visual context to navigate the unfamiliar landscape.

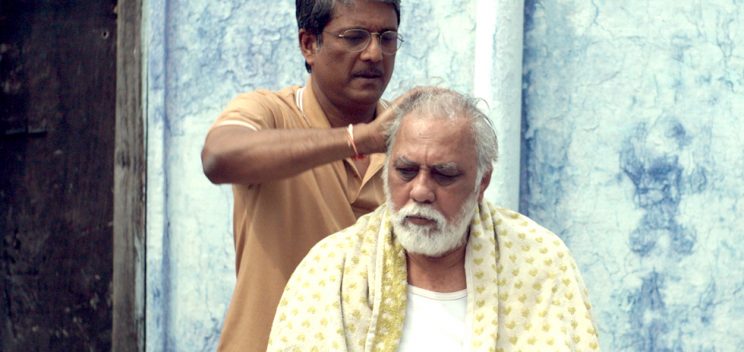

Lalit Behl is exceptional as the older patriarch of the family. At times, his character borders on senility, but Behl is always in control, never letting his performance slip into pantomime. Adil Hussain, as the son torn between the responsibility towards his father, accompanying him on the trip to Varanasi, and to his own family back home is perhaps a shade better. As he has shown in films like Sunrise (SFF 2015), Hussain has incredible command over subtle emotional textures, which he communicates through non-verbal body language. Of particular note are the scenes early in the narrative when Hussain’s character realises his father is actually serious about staying in the hotel. The micro-expression of incredulity mixed with resignation at his father’s decision is all on display on Hussain’s face; the performance in that moment is worth the price of admission alone. Palomi Ghosh as the granddaughter of the family shines in a limited role. In essence, the three generations of this family are where contemporary India finds itself.

Tajdar Junaid’s original score effectively complements the peaks and troughs of the narrative, the emotional beat through which the audience decodes the film’s silences. Bhutiani shared with us that he actually wrote the film with Junaid’s music in mind. His intricate knowledge of how and when to use Junaid’s composition elevates the experience of engaging with the narrative. Hotel Salvation is a strong addition to a recent resurgence among Indian filmmakers to share stories that are a lot closer to home. It is more than that, though, managing to convey a philosophical examination of where contemporary India finds itself now and where it sees itself headed in the near future.