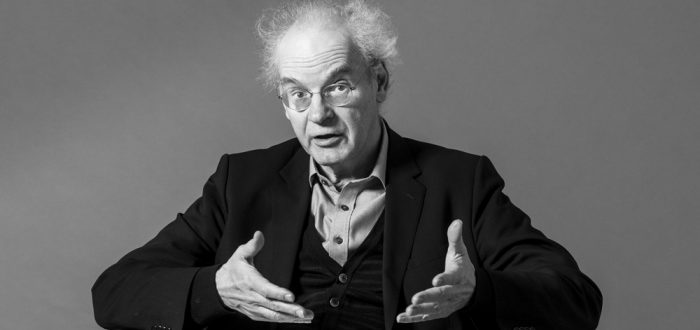

Visiting Australia for the first time, the French composer-filmmaker-theorist-critic Michel Chion will be giving a series of lectures on sound in cinema as well as a one-off performance of his composition, Requiem, along with two new works, The Scream and Third Symphony, at the Melbourne International Film Festival.

Chion began his musical career as an assistant to the musique concrète pioneer Pierre Schaeffer, creating experimental music programs for French radio as part of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales in the early 1970s. An avid cinemagoer, he began to teach sound in cinema in Paris, while also contributing to Cahiers du Cinéma, who published his seminal trilogy on film sound: La voix au cinéma, Le son au cinéma, and La Toile Trouée. After the publication of these three books in the mid-1980s and Audio-vision in 1991 — a kind of summary work that synthesised many of his earlier ideas — Chion established himself as arguably the world’s leading theorist on sound in film. Following the translation of his work into English by Claudia Gorbman and the publication of numerous other monographs on the cinema, his work has become a staple of academic film studies in the Anglophone world. I was one of countless humanities students that read Chion as an undergraduate, and I still remember reading his work for the first time and having the sinking feeling that all good art writing provokes: “Well, now I need to rethink everything I thought I knew.” Which, in hindsight, can only be a good thing.

In revisiting some of his work for this interview, it was exciting to see that not only did it still hold up, but that it remains quite clearly one of the most unique bodies of work read in academic film studies. There are, I think, two reasons for this. The first is that on a stylistic level, Chion’s writing has almost nothing to do with what we associate with the language of academia. While he shares a fondness for the invention of terms with his fellow psychoanalytic theorists, his writing has a clarity and sense of imagination that is so often lacking in academic writing, particularly the kind that slants theoretical. The second is that his outside perspective — drawing on his background in musique concrète — forces us to think about an ostensibly known object in an entirely non-habitual fashion. Reading his work, one has the strange impression of being shown something that was hiding in plain sight the whole time, but we just hadn’t thought to look or listen for it.

Reflecting Chion’s simultaneous interests in sound, experimental music, and cinema, the interview takes into account these fields that lie outside of the cinema with a view to better understanding his thinking as a whole.

Note: this interview was originally conducted in French and has been translated by the author.

First of all, welcome to Australia and thank you for sitting down to talk to us. If you don’t mind, I wanted to start with music, and more specifically musique concrète, a compositional form that your work has been associated with. It seems to me that with musique concrète, aside from its theoretical ideas surrounding the nature of sound, there was also a particular interest shown towards certain technologies capable of reproducing sounds (radio, the phonograph, etc.). Were you especially attracted to these technologies in and of themselves when you started thinking about music?

Well, for me, musique concrète is a form of that is made possible by technology – thanks to the tools that allow us to record and edit sound — but it is not technological, so to speak. It’s like cinema, which gives you the possibility to record movement and to perform montage. But the cinema can use a range of different technological means… After all, a piano is also a piece of technology. So for me, musique concrète is connected to technology only in the sense that it needs those recording and editing tools. Afterwards, one can create sounds and from there make works of what I call “fixed sound.”

It’s true that a recording gives us a completely different relationship to sound and music compared to hearing in the same space that a sound is produced. One of the central tenants of musique concrète is this idea of the acousmatique — that is, of sounds whose sources are hidden or obscured. What is the attraction for you of this causal obscurity?

That’s an interesting question, because in terms of musique concrète, it’s not so much the “hiddenness” of the source of sound that interests me, but the qualities of sound in and of themselves. The French composer François Bayle came up with the term “acousmatique music” to refer to the fact that we don’t see the source.1 For me, when I started making this kind of music, what interested me — and still interests me to this day — is making the sounds that I want without the limits and restrictions of instrumental music. This ability to fix and control sounds.

But this [control] is only possible in what I call musique concrète and others call acousmatique, that is, a music of fixed sounds. The fact that we don’t see the cause may add a poetic dimension to the experience. But I don’t think that’s the main thing that interests the listener; it’s the musical discourse [discours musical] and the sound. And so the cause no longer has importance, at least in musique concrète.

As for [the acousmatique in] the cinema, my interest laid in the fact that, after starting to work on sound in cinema, I noticed that certain films that had really impressed me depended on the separation of the voice from the body. This is linked to the history of various media. For example: radio. At the beginning of the 1920s, when the medium was in its infancy and was much more popular than it is now, people had to listen with headphones. Radio sets came at the end of the 1920s, and people began listening — collectively — to fictional programs and serials. Traces of this reappear in the first sound films developing at the same time, where we find these invisible characters and sinister masters.2 One associates the acousmatique dimension of radio with the image in cinema, and we see the creation of these effects that are by turns poetic and horrifying. I think this plays a very important role in the cinema.

On that note, you started your career at the radio, working for France’s ORTF.3 Did this experience working in radio influence your thinking on the cinema?

I think so. Although my entry into radio was quite serendipitous… I already had a link with radio from my childhood. Growing up, there was no television in the home where I was raised, nor at my parents’ place, so we spent a good deal of time listening to the radio. As a teenager, I loved listening to opera on the radio: I knew the story, I knew the libretto, and so I imagined the stage set. I did this of course without ever seeing these performances, but just using the libretto to spur my imagination. Besides, you go to the opera nowadays and people say that they wished that they’d kept their eyes closed! Sometimes the set is awful, though at other times it’s quite beautiful… So in any case, the radio was always there growing up, like for many others of my generation.

Right, because in France, television was much slower in coming to the home compared to other countries in the West. It wasn’t until the 1960s that people began to regularly own television sets, and even then, only little by little…

Yes that’s right, little by little… Of course, the radio has its own charms: you can listen to it while you work or do chores or while you eat. It’s a great source of pleasure to me even now! There’s a strong radio culture in France, as is the case in Germany. I don’t know about Australia…

Not as strong as in France, I don’t think…

There you go. Of course in France, we still have a few great radio stations: France Culture, France Musique. But there’s another kind of charm there with the radio…

For example, when you see people on television, there’s a whole host of distractions: we look at how they’re dressed, their makeup, all of which is of no interest. It’s their speech, their exchanges [with others] that matter. So I stayed quite attached to the radio and began working there. The funny thing was, when I started working [at the ORTF], I began to see these presenters who I only knew by voice, and who furthermore looked nothing like their voices! For example, there was a man who I’d listened to for years — I forget whom — with this low, deeply resonant voice. I ran into him and he was this tiny man… Anyway, I think this simple act of aural stereotyping taught me a lesson about the relationship between the voice and appearance that had some importance for me. I can’t see you right now — though I hope one day we’ll meet! — but all the same I have some vague impressions of you that I’m sure would be upset upon our meeting. Skype is complicated…

Absolutely! It’s interesting that you brought up the history of collective listening that marks radio as a medium. When you present your composition Requiem this week in Melbourne, the public will find itself together in an auditorium listening to a recording. How do you think people react to recordings in this environment where they are otherwise used to listening to music performed in person?

Well, often things remain the same. First of all, when I give a concert in public, there are about 10 or 12 speakers. I do perform to some extent in that space, in that I redistribute the sounds — composed for two audio tracks — into physical space. So there is a performative element, but it is rather discreet.

Second, now that people are used to going to electronic music concerts, or concerts where music is primarily performed from a laptop, there’s a different relationship. It is live, in a sense, but we see little of what the performer does. And even when we do see an orchestra performing, it’s amusing enough to see the first few times, but it soon becomes a matter of course. Or you go to an organ recital and don’t see a thing!

Almost by design!

Precisely, and it’s of little importance. So to me it’s not so different. I don’t see my works as recordings. When you go see a film in a cinema, you don’t see a recording. You follow the film, you read it (assuming that it holds your interest). It’s a well-worn comparison, but music is like a film for the ear — so I want people to live the work, not think of the apparatus. We are in the time of the work. [On est dans le temps de l’œuvre]

Let’s move on to cinema now. How did you come to the cinema? Did you have an especially cinephilic youth or did things happen a little later for you?

A little of both, I think. I adored the cinema, my parents too — my mother went to the cinema. But I didn’t start writing on film until the age of 30. I was looking for work, and I knew the medium well. Through musique concrète, I knew a good deal about the technical aspects of sound. On the other hand, learning Pierre Schaeffer’s listening techniques gave me a perspective on sound that was not necessarily medium-specific. This perspective was related more to the form of sound itself, and this gave me a richer understanding.

At the end of the 1970s, there was a quite happy coincidence: while I was looking for work, VHS appeared, which allowed you to watch films in the comfort of your own home or in a classroom with students. It also gave you the ability to cut the sound, or cut the image, and to observe the relationship between sound and image. Pierre Schaeffer recommended me as someone who could teach on this subject; it’s thanks to him that I began to teach sound in cinema. And then, because very few people had written on the subject of sound, I started writing books and contributing to cinema revues. My books started to be translated… And so the cinema became one of my principal focuses.

I also directed a couple of short films and made video art works where I composed the images as well as the sound. For example, on Thursday, Requiem will be followed by two audio-visual symphonies [The Scream and Third Symphony]: I did everything there, sound, image, montage. So, again, we might call my involvement in the cinema the product of circumstance…

It’s interesting to hear you talk about the importance of VHS in this series of circumstances that led to your involvement in cinema. You’re right in that this classic exercise that we continually see in your writing — that of cutting the sound, cutting the image, seeing what happens — is only possible with the advent of VHS. So I wanted to ask, to what extent did these non-traditional viewing and hearing settings open up new perspectives for your thinking on cinema?

Well, in the past, when one wanted to study a film, it was a matter of going to see it several times in the cinema, or even (if you were lucky) at home on the television. But it was always an end-to-end screening. With VHS and then the DVD, you could really look and listen like you couldn’t before. It’s like the passage from the era when literature was read aloud – people would come to listen to a poem – to the era of the printing press. All of a sudden, everyone could read and re-read a passage of a book in their own home. It was a revolution, that’s for sure.

I remember showing a film to students while I was teaching in Paris, and they said “Why did Kubrick leave that mistake in?” (Mistake in inverted commas, of course – I think we were watching Barry Lyndon, of all films!) And I had to remind them that it’s a matter of how we watch nowadays, and that this inevitably changes how one composes a film. Of course, there are films from the pre-VHS era that are meticulously crafted: we watch Hitchcock in detail and are constantly astounded, of course.

To me, I think it has above all changed the methodology of cinema studies at universities. Of course, it gave us the chance to examine film in the same manner that we might observe a painting, or a passage of literature, and this changes the entire analytic structure…

Yes, but I think there’s a paradox there as well. In the period in which it was difficult to obtain a copy of a film, a researcher like Raymond Bellour or me would count themselves lucky to have a copy of a film for three days. They would take detailed notes on the shots and decoupage of a sequence. And now that people can have two thousand films in their own home, the books have become much more generalised. My problem with Deleuze’s cinema books and others like them is that they don’t examine the film as a text in detail, but rather address cinema in the abstract. So the paradox is that even though we can easily do close analysis, the interest seems to lie elsewhere at the moment. While I was writing for Cahiers du cinéma in the ’70s, critics would do sequence analyses image by image, all while having to hunt down a copy of this or that film. I find it very strange that so few people do that today.

Maybe nowadays people feel like they’ve seen too many films…

Yes, or perhaps they feel like they’ll never have the time to see enough. It’s the same thing with music: people have two thousand songs on their phone and tell themselves that they’ll never have the time to listen to them all.

Speaking of Cahiers, were you consciously thinking about this type of engagement with cinema — of tracing aesthetic links across an œuvre — that we associate with auteurist studies? There seems to be a regular stable of directors — Tati, Bresson, Lang — that you refer to fairly consistently throughout your books on cinema.

Well yes, for the most part. And I’ve written books focusing on the bodies of work of particular directors; I wrote on Kubrick — a long book at that — and also on Tarkovsky and Lynch. Often it was by chance, but it was usually me proposing ideas for a book based on a director whose work I loved. And of course, like that I could make a living and work on my musical composition as well; I’ve never especially enjoyed composing for other peoples’ films or for ballet or anything like that. So I make a living writing and compose at my own pace.

But I think there’s something interesting about this question of books and auteurs. One could write a 500-page book on a single, great film. But there are great films that aren’t studied enough because there is no great auteur at the helm. For example, there’s a film that I find to be absolutely sublime, Kiss Me Deadly. You know it?

Yes, by Aldrich.

It’s an extraordinary film! But because there are very few books about Aldrich, and people say “Oh but Aldrich isn’t a great auteur, where as Fritz Lang or Hawks…” It makes no difference to me. Kiss Me Deadly is an incredible film! And we could write a 500-page book about it, because it teaches us an enormous number of things, and of course it’s a magical work. So, in the same way that there are major books dedicated to certain paintings, I think that we could do the same for certain films. There are some collections that do this, but very few.

I’ve written a monograph on Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, but it was tiny thing done for an English publisher, and another on City Lights that is now out of print. I don’t have much desire to write books at this stage — I’m 70 years old and I’d like to get on with other projects. But I think in any case we ought to be dedicating books to single films, and especially those that don’t have a great name attached to them. West Side Story is another one, a great film. But again, Robert Wise isn’t a name that people recall so this book doesn’t exist. It’s a shame.

Yes it’s something that I’ve noticed as well, it’s a real shame. Another thing I’ve noticed in your work is your interest in how we perceive and localise sound as spectators, and how this changes in different viewing conditions: with headphones on a plane, or in multi-track Dolby in a state-of-the-art cinema.

Yes of course, and at home you can now have a specialised experience with sound. People often have two or more speakers. And in the cinemas, the special effects related to sound are often relatively limited. There’s no point in having the sounds wander about the theatre just because the possibility is there. Even with current popular cinema, which is full of dialogue, or Terrence Malick’s most recent film, Song to Song, where we have interior voices, music, all sorts of sounds — even then we don’t have the feeling that sound is promenading around us in the theatre. It still remains “stuck” to the screen, so to speak. So I get the impression that current films are made — consciously or unconsciously — by people that know that the film will be seen and heard either in a cinema equipped with multi-track sound, in a plane wearing headphones, on a computer, at home etc. The film has to be compatible with all of these conditions.

So people are thinking much more consciously of this now.

Certainly, certainly. That is to say that if you take a film like Cuarón’s Gravity, which is made in 3D, the film was conceived so that we could also watch it on a flat screen. There’s an obvious economic motivation for this. Sure, you could make a film that could only be seen in theatres equipped with 10 speakers, but that just doesn’t happen.

This isn’t especially new, though. People thought about this when making colour films while television was still for the most part broadcast in black and white: they’d say, “Alright, we can’t make everything depend on colour because the film still has to make sense in black and white.” With the coming of language into cinema, these issues of course became especially pronounced, and sound films had to be adapted for international distribution via dubbing or subtitles. Or if we take the example of orchestral music in the 19th century, when one wrote a symphony, the opportunity to perform the work with a full orchestra rarely presented itself. So composers would transcribe works written for a 50-piece orchestra for one or two pianos, and this is what people would listen to!

Yes, I suppose it’s hardly a new problem. To finish, I have a question about a passage in your book Le son au cinéma that has always interested me, mostly because of its relevance to an issue that is still debated today in cinema. In the book, you give a short critique of what you call the “Neo-Lumièrist” tendency in cinema, represented by the likes of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, Eric Rohmer, who are strong believers in direct sound–

I don’t criticise them!

Perhaps criticise is the wrong word, but you speak with a little more nuance than usual on the choice of these and other directors to commit to direct sound, which is a choice that often has ideological or political reasoning behind it. What do you think of this continued interest in direct sound, which is still something that certain directors stand behind today? Why this continued attraction to it?

Well it’s hard to say, there does seem to be a sort of “magical” aspect to it. I knew and liked very much Danièle Huillet — who has now unfortunately passed away — and Jean-Marie Straub, both as people and as artists. It wasn’t so much their position that I was critiquing, because theirs was coherent. Rather, it was the people who had a doctrinaire attitude where they would say, “All films must be shot with direct sound” or something similar. I found this to be an absolutist position that was idiotic, because these people didn’t realise that at least nine-tenths of all films in the world are made with post-synchronised sound. It’s great if people have a position, but one must not be ignorant.

For example, there were some great films from the start of the New Wave — Godard’s Breathless, Truffaut’s first films — that were post-synchronised. And people in France believed and wrote foolishly — and I really mean foolishly, without trying to find out what was really going on — things like “These films have the naturalism of direct sound.” It was senseless! These films were completely post-synchronised. So of course a film’s naturalism has nothing to do with the fact that we record sound at the same time that we shoot.

But on the other hand, with Straub and Huillet, I respect their position because there is a coherency to it, and above all they knew what they were doing. And at the same time, they saw a short film that I directed, Eponine, and they said, “Michel Chion might do something else, but this is how we do it.” It wasn’t a doctrinarian position. Whereas it was others in France who insisted on the rigidity of this position.

Yes, above all it seems in the theoretical debates of the 1970s.

Yes exactly, it became a theoretical doctrine.

Let’s leave it there. Thank you once again, and best of luck in Melbourne this week.

Pleasure, and thank you!