This feature piece is published in partnership with Melbourne International Film Festival’s Critics Campus program. The film A Gray State screened at the festival this year.

Late in Erik Nelson’s new documentary A Gray State, the father of David Crowley – an alt-right filmmaker who killed his wife and child before turning the gun on himself – reads a line from his deceased son’s diary. The younger Crowley writes that he will “destroy” his best friend. Crowley’s father looks off-camera and says, with a quivering voice, “David didn’t mean that. That was just him being creative.”

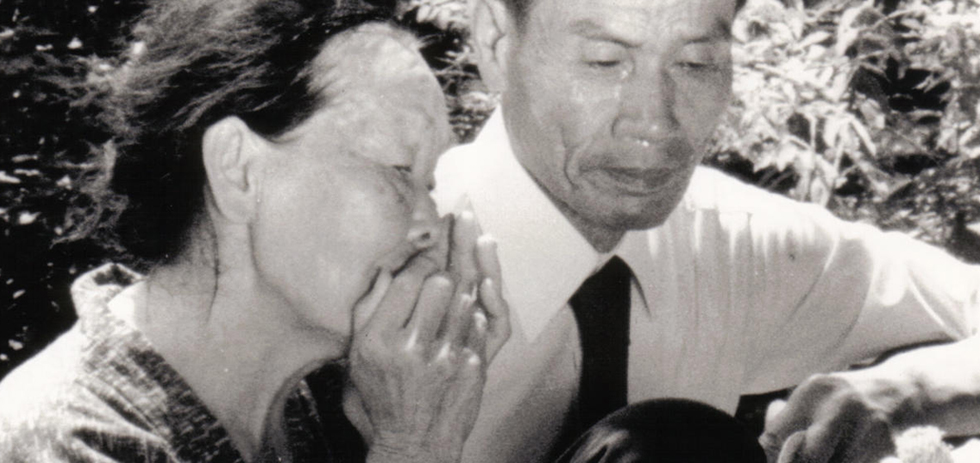

At the end of Kazuo Hara’s 1987 Japanese documentary The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, 62-year-old Kenzo Okuzaki is sentenced to 12 years in prison for attempting to murder the son of his old army officer. When Kenzo’s wife, Shizumi, is interviewed outside the prison, she offers that she is happy for her husband, because he “did what he could, so he’s satisfied.”

Despite the violent acts perpetrated in the name of their political ideals, the family members of David Crowley and Kenzo Okuzaki defend the behaviour of these men to (and beyond) their deaths. As the old proverb goes, “Blood is thicker than water.”

A Gray State follows Crowley, an ex-soldier and aspiring filmmaker who became unhinged in the process of making his magnum opus Gray State, a dystopian thriller in which government troops forcibly take over the country. Before he could finish his film, Crowley shot his wife and daughter, wrote the words “Allahu Akbar” on the wall with their blood, and then shot himself. This is seemingly all because of an imagined conspiracy, the details of which Nelson’s documentary never makes clear.

Also unclear is the path Crowley took from an ideological association with left-leaning libertarianism to a darling of the alt-right. Disillusioned by his two tours in Iraq, Crowley openly advocated for less governmental control over all aspects of American society. He was married to a Muslim woman, yet Nelson’s documentary never shows Crowley using any of the racial rhetoric commonly associated with the alt-right movement. Even so, Crowley’s own film found its biggest Kickstarter supporters in those cut from the conspiracy theory/Timothy McVeigh cloth. There’s a sequence in A Gray State where we are witness to Crowley’s responses to complaints from his supporters about the delay of his film; in the montage of videos he is defensive and pleading, almost pathetic. For a man purportedly standing in staunch opposition to groupthink, Crowley quickly fell under the sway of the alt-right, his views (and his film) warping under the pressure of a movement who saw him as a potential hero. He became convinced of a conspiracy, vaguely resembling that in his film, to overthrow him and his family. His fear was so strong that even his wife Komel began having visions of violent rapture.

Where Crowley begins his film in a state of relative innocence before descending into paranoia, the protagonist of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On is presented as extreme from the very beginning. Kenzo Okuzaki drives a van covered in anti-emperor rhetoric, yelling at pedestrians with a megaphone about government horrors, but director Kazuo Hara, witness to the free-form radicalism of the Japanese New Wave, manages to present his subject’s screaming political agenda with an almost subversive nonchalance. A simple title card informs us that Kenzo has already been imprisoned for firing ball-bearings at the emperor, and now he’s got a new target: his old army superiors. Kenzo believes they killed and then ate his fellow soldiers in Papua New Guinea near the end of World War II. His investigative methods are as straightforward as David Crowley’s were muddled: he decides to confront his ex-superiors and ask them point blank if they cannibalised his comrades. If they fail to answer, Kenzo will beat the shit out of them. And so he does, seemingly with great glee. Whereas A Gray State tells us much about Crowley’s history and home life, Naked Army steers clear of Kenzo’s background and personal life. What we learn about him, we learn through his actions alone, each successive confrontation revealing a little more about Kenzo’s deep sense of injustice.

What we do learn, though, is hilariously banal. Shizumi is just as loving as Crowley’s wife was, offering vague statements of support for Kenzo and his violent methods. Crowley’s friends and family continually defend him and his behaviour, even as the story eventually reveals a cruelty tingeing his paranoia. A central problem for the friends and family of these men, it appears, is separating them from their views. Crowley appeared to be a charismatic leader and loving family man. Home video footage shows him exerting a firm but restrained control on the set of his film. He cuddles his family at home, even if he occasionally spouts strangely blunt advice about death and murder to his four-year old daughter.

But what happens when a person you know transforms? If you’re Komel, you leave your friends behind and become consumed by the charismatic soldier in your home. Though Crowley’s family describe her as “intelligent” and “strong-willed” (they use these adjectives so often it feels like they’re surprised a wife could have these traits), they also note Komel’s growing deference to her husband. In the same breath, Crowley’s father, brother and close friends defend him to the end of this documentary. They have trouble speaking about his crimes, but words like “loving” still roll off the tongue. When they do talk of his transgressions, they speak of them in the abstract, as manifestations of Crowley’s political extremism. And yet they cannot even find the words to denounce his politics. They know, deep down, that Crowley’s views had become so integral to his identity that denouncing them would be denouncing him.

The big difference between the two men is that, despite Kenzo Okuzaki’s lunatic appearance, he was right: there was a conspiracy. His fellow soldiers, chosen arbitrarily by his superior officers, were eaten. But by the end of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, Kenzo seems just as crazy as Crowley does. Whatever truth Kenzo sought out, the nobility of his intentions sometimes feels undercut by a his seemingly gleeful bloodlust. Maybe, like Crowley, Kenzo was taking out some of his own self-loathing on these men. He despised the war, sure, but he also engaged in it. He watched these crimes being committed, and he stood there, horrified but complicit. Hatred flows in multiple directions through them, but Kenzo was able to direct his hatred outwards, rather than striking those closest to him.

Violence is a galvanising force in A Gray State and The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On. Even before he murdered his family, David Crowley was working on a film about responding to theoretical government executions. The tagline on his poster was “By Consent or Conquest.” Kenzo Okuzaki had already been to prison for an attack on the emperor, and an attempted murder would land him there again by the end of the film. David Crowley and Kenzo Okuzaki aren’t just similar because their extremism, or their conspiracies, or their ambition. There’s a kinship in their stories because of what they lost, and how they lost it. A variation on the old aphorism might be more appropriate for them: “The blood of the covenant is thicker than the water of the womb.”